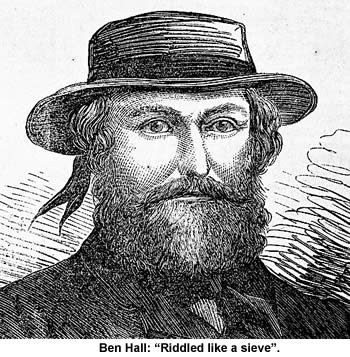

Ben Hall inspired a whole host of ballads, but this is by far the most famous. A 1971 recording by AL Lloyd and Trevor Lucas produced cover versions by some of the biggest names in UK folk, including Martin Carthy and June Tabor.

Ben Hall inspired a whole host of ballads, but this is by far the most famous. A 1971 recording by AL Lloyd and Trevor Lucas produced cover versions by some of the biggest names in UK folk, including Martin Carthy and June Tabor.

The Background

This version of the song was collected by John Manifold, who heard a woman called Ewell singing it in the back room of a Brisbane pub, and is preserved in 1964's Penguin Australian Songbook. It's clearly based on a slightly clumsier 1911 version said to have been written by Hall's brother-in-law John McGuire. The song's modern fame began to spread with Trevor Lucas's performance on AL Lloyd's album The Great Australian Legend. Whenever one of Lucas's small changes to the lyrics appears on a later recording - "terrible tale" rather than "sorrowful tale" for example - it's a safe bet the new singer learned Streets of Forbes from that 1971 disc.

The Ballad

Come all you Lachlan men and a sorrowful tale I'll tell

Concerning of a hero bold who through misfortune fell

His name it was Ben Hall, a man of good renown

Who was hunted from his station and like a dog shot down

Three years he roamed the roads and he showed the traps some fun

A thousand pound was on his head with Gilbert and John Dunn

Ben parted from his comrades, the outlaws did agree

To give away bushranging and cross the briny sea (1)

Ben went to Goobang Creek and that was his downfall

For riddled like a sieve was valiant Ben Hall

'Twas early in the morning upon the fifth of May

When the seven police surrounded him as fast asleep he lay

Bill Dargin he was chosen to shoot the outlaw dead

The troopers then fired madly and filled him full of lead

They rolled him in his blanket and strapped him to his prad

And they led him through the streets of Forbes to show the prize they had (1)

The Facts

The John McGuire version of this song I mentioned above appears in the April 30, 1911 edition of a Sydney newspaper called Truth, which was serializing McGuire's ghost-written memoir Early Colonial Days. It has its merits - I like "chap" rather than "man" in the first verse for example - but you can see why whoever picked up the song next decided it could do with a bit of a polish. Their first task was to fix the crumbling scansion of McGuire's second verse here:

On the fifth of May, when parting from

His comrades all along the highway

It was at the Wedding Mountains those three outlaws did agree

To give up bushranging and cross the briny sea.

The article continues with a prose extract from McGuire's book, explaining that he'd been convalescing from an injury in Forbes when the troops brought Hall's body through on the morning of May 5. As I've already described, they'd ambushed Hall at his campsite earlier that day, firing some 30 bullets into his body before they were done, then - according to McGuire - decided to show off their trophy in a small parade through the nearest town.

"They passed the house where I was, Inspector Davidson leading the packhorse with a very large swag on its back and a black poncho thrown over it," McGuire writes. "I saw the legs of a man dangling down over the horse's shoulders. I soon discovered that it was Ben Hall." The troops put Hall's body on display at Forbes' police barracks. Somewhere between 400 and 500 people filed past to see it there, some to pay their respects and others simply to gawp at a butchered celebrity.

McGuire went to view the body too. "He was a mass of gunshot wounds, principally the lower part of his body," he later recalled. "He was literally torn to pieces like an old red rag. We counted 32 gunshot wounds. This was the most cowardly and disgraceful business that could possibly be done." The Western Examiner paints a very similar picture, saying Hall's body was "pierced by bullets and slugs from his feet to the crown of his head". Charles Asenheim, the doctor who carried out the post-mortem, was unable even to guess which particular bullet had killed the bushranger. It could have been the one he'd found between Hall's shoulders, he said, either of the two in his brain or any of the multitude piercing vital organs. (2)

Unlike our previous Ben Hall ballad, Streets of Forbes gives Billy Dargin, the troops' native tracker, a central role in the shooting. There's some support for this idea in a 1911 letter to Truth from a man called Jack Quinn - most likely Ned Kelly's uncle of that name. Kelly's Jack Quinn spent his own 1860s in constant battles with the police and so was well-placed to hear all the era's gossip from police and criminals alike. I can't prove he's the same Jack Quinn who wrote the letter, but it certainly reads that way. (3, 4)

According to Quinn, it was Hall's own camp which the troops surrounded - not just his horses - and they sent Dargin in alone to fire the first shot. "Billy Dargin got down into the creek at break of day," Quinn writes. "As Ben lay with his head on his saddle towards him, asleep, the tracker fired and put the bullet in the top of his head, which came out under his eye, alongside his nose. Ben sprung to his feet, clung to a sapling, and stayed there till they cut him down."

Matthew Holmes, the director of 2016's The Legend of Ben Hall, and his historical adviser Peter Bradley dismiss this take on the story completely. The idea of Dargin as the real killer starts with a supposed confession from Dargin which McGuire claimed he'd heard, but which has never been verified, they point out on the film's commentary track. Quinn's version seems drawn from the same dubious source, so we should take them both with a substantial pinch of salt. (5)

Hall's relatives, led by his brother Bill, collected the bushranger's body from its slab in the police barracks on the morning of Sunday May 7, placing it in a handsome black coffin with gilt trim. The Western Examiner's Forbes correspondent was there to report on the whole day's ceremony. "At about 2 o'clock in the afternoon individuals began to collect in the neighbourhood, and soon after the face of the corpse was exposed, so that those who had not seen it on Saturday now had the privilege," he writes. "A great many availed themselves of the opportunity. When his brother's wife was turning from a last look, it is said she remarked that, 'had it not been for Ben Hall's wife, he would not have been lying there'." (6, 7)

The funeral procession set off for the cemetery at at about 4:00pm, led by Hall's body in an ornamental hearse drawn by a plumed black horse. Three carriages followed behind, plus 40 or 50 mourners on foot. At the cemetery, they found another 100 or so people, including, the WE man says, "between 40 and 50 females, young and old". His implication is that these women - particularly the younger ones - were there not because they know anything about Ben Hall's career, but simply because they'd fancied the pants off him. A century later, they'd have been mobbing The Beatles, but for now a handsome bushranger's funeral would have to do.

Less than a year after Hall's death, both Gilbert and Dunn were in the ground too. Hearing of their friend's fate, they took refuge at the Binalong home of Dunn's grandfather John Kelly. He promptly decided to turn them in and claim the reward. On May 12, 1865, the night before the raid, Kelly poured a bucket of water over Gilbert's rifle to sabotage it. Hearing a commotion next morning, Gilbert snatched up the gun and fled with cops at his heels.

He didn't get far. "When Gilbert reached the edge of Binalong Creek, he took up a position behind a tree and took aim with his Tranter revolving rifle, but it misfired" Peter Smith writes in his 1982 book Tracking Down the Bushrangers. "[He] ran along the dry creek bed as Senior Constable Hales and Constable Bright opened fire. The bushranger fell heavily and did not get up again. Bright's shot had gone through his heart." (8)

Dunn was wounded in the same shoot-out, but managed to escape to Bogolong Station, where a sympathizer patched up his wounds, fed him and supplied a horse. Seven months later, on Christmas Eve, he was holed up in the Macquarie Marshes with another fugitive called "Yellow George" Smith when the police caught up with him again. It was Smith they were looking for that day, but a Constable McHale recognised Dunn there too and another gun battle resulted. This one ended in Dunn's arrest.

He was tried for the murder of Constable Samuel Nelson - an incident from his days with Ben Hall - found guilty and sentenced to hang. The sentence was carried out on March 19,1866, at Darlinghurst Gaol with a crowd of about 60 or 70 people watching. Dunn was just 19 when the rope broke his neck. (9)

The Facts

One of the more entertaining myths about Ben Hall's death has Mary Connolly, wife of the traitorous Mick, running on to the scene just as the final shots were fired.

One of the more entertaining myths about Ben Hall's death has Mary Connolly, wife of the traitorous Mick, running on to the scene just as the final shots were fired.

More fanciful still, we're told she was pregnant at the time with Hall's son and that, when the boy was born, his skin was speckled with dark spots exactly matching the pattern of his father's bullet wounds. "I saw the boy a few years ago with the marks of Ben Hall on him," Jack Quinn claims in his 1911 letter. "The first mark to be seen is alongside his nose, where the bullet came out of Ben Hall."

In his 2010 book, Australian Folk Songs & Bush Ballads, Warren Fahey mentions rumours of this lad billing himself as "The Leopard Boy" in a touring sideshow. Checking the archive, I discovered there really was a performer using this name on New South Wales' sideshow circuit a few years after Hall's death. A May 1875 clipping from the Miner's Advocate reviews a recent show in Wallsend which also featured a lady dwarf and a dog who could play euchre. "The Leopard Boy is the subject of much speculation," the paper says. "[But] personal scrutiny is calculated to convince any person that he is a genuine wonder." (10)

There's no suggestion in the paper's story that the Wallsend attraction claimed any relationship with Ben Hall, but making that link must have been very tempting for any Australian sideshow entrepreneur at the time. Mottled-skin performers using the "Leopard Boy" billing were fairly common in the sideshow era, and my guess is that one of them cooked up the supposed connection with Hall's death to boost his ticket sales down under. Perhaps that's where the rumour Fahey cites began?

The Music

The Streets of Forbes is one of the most recorded bushranger ballads. In my Spotify playlist PlanetSlade Bushrangers, I've included versions by Gary Shearston, AL Lloyd (with Trevor Lucas) and June Tabor.

Sources & footnotes

1) In the Australian slang of the 1860s, mounted troops were known as "traps" and a horse was a "prad".

2) Western Examiner, May 1865 (exact date unknown).

3) Quinn's letter suggests he's an old mate of John McGuire's, asking the paper for his address "so that I could have a chat with him about old times". He also seems to know many of the troops involved in killing Hall: "I heard Tim Hipkiss say. Constable Buckley told me. I knew Jack Bowen well." and so on. Finally, there's a veiled threat against Bowen, hinting that Quinn has some incriminating information against the officer.

4) The letter appeared in Truth's May 21, 1911 edition.

5) Holmes and Bradley are equally skeptical about the song's triumphant parade. They believe Davidson's squad brought Hall's body into the town as discretely as they could, and that it was only after they'd laid it out at the police barracks that anyone in Forbes realised what had happened.

6) This Western Examiner report was reproduced in the Cornwall Courier of May 27, 1865.

7) Bill's wife is referring to Bridget Hall's 1861 decision to desert her husband for a new lover, taking Ben's young son with her as she left. This is generally agreed to be the first step in a string of ill fortune which made Hall bitter enough to turn criminal. See my piece on The Death of Ben Hall for details.

8) Tranter guns were among the finest weapons of their day, and you can see photo of their revolving rifle here. These were issued to New South Wales police, suggesting Gilbert probably stole his from an officer he'd shot or bailed up.

9) All the bushrangers in this story died young. Hall was 27 when shot by police and Gilbert just 22.

10) Miner's Advocate & Northumberland Recorder, May 19, 1875.