It's always easy to romanticise Australia's bandits as good men, driven to crime only by the persecution of their unjust British rulers. In Ben Hall's case, this actually seems to be true.

It's always easy to romanticise Australia's bandits as good men, driven to crime only by the persecution of their unjust British rulers. In Ben Hall's case, this actually seems to be true.

The Background

There are a lot of ballads about Ben Hall, but the one I've chosen here is the most literary of the bunch. Its careful composition and unusual rhyme scheme marks it as the work of a single writer rather than a song that's emerged from the folk process. The earliest version I've seen appeared in a Sydney magazine called Smith's Weekly on September 27, 1924, where it's credited to the bush poet William H Ogilvie. I've cut the magazine's original 19 verses down to 12 here so we can focus on the ballad's core story.

The Ballad

Ben Hall was out on the Lachlan side

With a thousand pounds on his head

A score of troopers were scattered wide

And a hundred more were ready to ride

Wherever a rumour led

They had followed his track from the Weddin heights

And north by the Weelong yards

Through dazzling days and moonlit nights

They had sought him over their rifle sights

With their hands on their trigger guards

The outlaw stole like a hunted fox

Through the scrub and stunted heath

And peered like a hawk from his eyrie rocks

Through the waving boughs of the sapling box

As the troopers rode beneath

And every night when the white stars rose

He crossed by the Gunning Plain

To a stockman's hut where the Gunning flows

And struck on the door three swift, light blows

And a hand unhooked the chain

And the outlaw followed the lone path back

With food for another day

And the kindly darkness covered his track

And the shadows swallowed him deep and black

Where the starlight melted away

But his friend had read of the big reward

And his soul was stirred with greed

He fastened his door and window-board

He saddled his horse and crossed the ford

And spurred to the town at speed

He reined at the court and the tale began

That the rifles alone should end

Sergeant and trooper laid their plan

To draw the net on a hunted man

At the treacherous word of a friend

Ben Hall lay down on the dew-wet ground

By the side of his tiny fire

And a night breeze woke, and he heard no sound

As the troopers drew their cordon round

And the traitor earned his hire

And nothing they saw in the dim grey light

But the little glow in the trees

And they crouched in the tall, cold grass all night

Each one ready to shoot on sight

With his rifle cocked on his knees

When the shadows broke and the dawn's white sword

Swung over the mountain wall

And a little wind blew over the ford

A sergeant sprang to his feet and roared

"In the name of the Queen, Ben Hall!"

Haggard, the outlaw leapt from his bed,

With his lean arms held on high

"Fire!" And the word was scarcely said

When the mountains rang to a rain of lead

And the dawn went drifting by

And I know when I hear that last grim call

And my mortal hour's spent

When the light is hid and the curtains fall

I would rather sleep with the dead Ben Hall

Than go where that traitor went.

The Facts

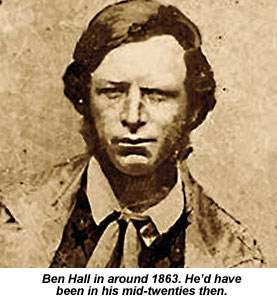

Ben Hall was born at Wallis Plains in New South Wales on May 9, 1837, the son of Benjamin Hall and Eliza Somers, two transportee convicts who'd married after meeting in the colony. Benjamin - a ticket of leave man - worked as overseer at a Murrurundi cattle station, later moving the family to new station near Forbes, where Ben started working alongside him at 14. When his father moved north again in 1855, Ben, now 18 and an accomplished stockman in his own right, stayed put.

This was a life outside the boundaries of NSW's 19 counties - and hence outside the reach of any colonial law as well. "For fifteen or twenty years the Hall family and the other families out there were basically running their own show," the Australian song collector and researcher Jason Roweth told me. "They were out there without anyone overseeing them in terms of British justice. Almost all of them had a parent who'd been a convict, so they'd been through those cycles of dispossession and dislocation. I think for the first time in their lives, they felt they'd found a home. They thought they'd found their republic." (1, 2)

At first, the authorities had little incentive to change any of this. Many of the men occupying these lawless areas were escaped convicts and only a very foolhardy trooper would confront men like that in such a wild land. There was also the point that much of the colony's food supply depended on the beef that these "beyond location" farms were raising. In was only when the Australian gold rush began in 1851 that the colony's British rulers decided they'd better reassert their hold.

"As soon as gold is found, you've got enormous wealth," Roweth says. "You've got an enormous population streaming into the country, plus the arm and law of British justice acting to reclaim those areas. I think the spark for Ben Hall and the other Weddin Mountain bushrangers comes down to that: 'We had something here and now it's being taken away from us'."

A year after parting from his father, Hall was working at John Walsh's Wheogo cattle station, where he met and married the boss's daughter. Bridget Walsh was just 16 when they wed, and she quickly gave him two children: the first died in infancy but the second, a boy named Henry, lived. He was born in 1859, the same year Hall teamed up with John McGuire to lease a 10,000 acre plot of land at Sandy Creek, about 30 miles south of Forbes. The two men were related through McGuire's marriage to Bridget's sister Ellen and now planned to set up a cattle station of their own.

A year after parting from his father, Hall was working at John Walsh's Wheogo cattle station, where he met and married the boss's daughter. Bridget Walsh was just 16 when they wed, and she quickly gave him two children: the first died in infancy but the second, a boy named Henry, lived. He was born in 1859, the same year Hall teamed up with John McGuire to lease a 10,000 acre plot of land at Sandy Creek, about 30 miles south of Forbes. The two men were related through McGuire's marriage to Bridget's sister Ellen and now planned to set up a cattle station of their own.

That's where Hall seems first to have encountered a local crook called Frank Gardiner. One of Gardiner's rackets was a joint venture with the Spring Creek butcher William Fogg, who'd slaughter the stolen cows Gardiner brought him and sell their beef in his shop. John Manifold, writing in his 1964 book Who Wrote the Ballads, thinks Hall and McGuire might have sold some of their beef through Fogg too. "Naturally, they sold to the butchers on the diggings," he writes. "Probably they sold, innocently enough, to the firm of Gardiner and Fogg. Almost certainly, they harboured Gardiner when he was on the run - hospitality is hospitality. But nothing in the character of either man justifies Sir Frederick Pottinger arresting Hall for 'highway robbery under arms' during the race meeting at Forbes on 22 April 1862."

We'll come to that incident in a moment. First, though, we need to cover Bridget Hall's desertion of her husband in the summer of 1861. Here we can turn to an account from John McGuire's memoirs, where he hints that his own wife Ellen already suspected Bridget was having an affair with a married ex-cop called Jim Taylor who lived about 25 miles from Sandy Creek.(3)

"The rascal watched for his opportunity," McGuire says. "That opportunity came when Ben and I and most of the stockmen went away for several days to gather wild horses. Our rations getting short before the job was finished, I rode home to procure more and it was on reaching my home that my wife informed me that she had missed her sister and believed that Taylor and she had eloped. Together we went over to Ben's house to search the place. The side saddle was gone, and everything seemed to confirm the opinion expressed by my wife."

Not only that, but Bridget had taken Henry with her. "I rode back to the camp and broke the news to Ben, who was cut up terribly, for he had been fond of his wife and his little boy was the sunshine of his home," McGuire continues. "For three of four days, Ben raced about, but could not get a clue as to the direction taken by the pair. He abandoned the search in despair and from that day out his life was a reckless one."

That was step one in the process of brutalization that drove Ben Hall to become an outlaw. Step two came about eight months later. Here's McGuire again:

"It was early in the month of April 1862 that Ben and his stockman Jack Youngman were riding together in the bush when they came out on the Pinnacle road. They had not proceeded far along that road when Frank Gardiner came galloping up and rode with them. About half a mile further on they came up with a dray, which was driven by a man named Ferguson. Gardiner, drawing his revolver, ordered the driver to stop. At the same time he ordered Ben Hall and Youngman to stay there on their horses. Ferguson recognized Gardiner and was very prompt to obey his orders.

"About a fortnight later, Ben and I attended a two-day race meeting at Forbes. After dinner, to my surprise, I saw Ben riding past the booth with a constable on either side, so I rode over and enquired of him what was the matter. 'Blessed if I know,' says Ben. I directed my enquiries to the police but they could give no satisfaction and suggested I should go and see Frederick Pottinger."

Pottinger was a local Wales police inspector who yearned to prove himself the scourge of the bushrangers. When McGuire pursued the matter with him, Pottinger told him Hall had been identified as one of the men responsible for the Pinnacle road robbery and was currently in lock-up awaiting trial on those charges. That's where he stayed till the trial acquitted him on lack of evidence about a month later. "The owner [of the dray] swore that, from his distance of 200 yards he recognised Hall at the stuck-up dray," McGuire recalls. "But the driver gave contradictory evidence: he swore that Ben was not one of the men." (4)

A few days after the trial, McGuire adds, Gardiner called on Hall and apologized for the trouble he'd caused him. He gives us Hall's reply too: "It's done now and can't be helped. But the next time they take me, they'll have something to take me for."

On June 15, 1862, Frank Gardiner led a gang of eight men in the successful robbery of a coach transporting cash and freshly-mined gold along a road near Eugowra, 23 miles east of Forbes. They got away with a haul worth over £14,000 - a vast fortune at the time - and both Hall and McGuire were among the many men arrested on suspicion of being involved. They were locked up while the police continued their investigations and Pottinger, still smarting from his failure to convict Hall for the Pinnacle road hold-up, sent men out to burn his Sandy Creek homestead and shut all his and McGuire's livestock in a paddock where they knew the animals would starve to death.

Dan Charters, one of the other suspects arrested for the Eugowra job, turned Queen's evidence, identifying Frank Gardiner and several other men as having taken part in the robbery. McGuire had been an accessory, he said, but Ben Hall was entirely innocent. Once again, Pottinger was forced to let Hall go free. He'd had been in jail for two months this time, returning home to find what Manifold calls "the smoking ruins of his home and the stinking corpses of his cattle". This was step three, and it set Hall on the path he'd follow till death.

"Ben Hall was not a major criminal, or even necessarily a criminal at all," the Australian researcher Keith McKenry told me. "But he'd made some enemies in the police and they allowed all his stock to die. He came back, found his farm was effectively destroyed and took to a life of crime, having been made destitute by the failure of the farm. He became, effectively, a reluctant bushranger." (5)

Fast forward to June 1863, and we find Hall running with Johnny Gilbert (another of the men Charters fingered for the Eugowra robbery) and an equally questionable character called John O'Meally. "The trio had started a programme of almost daily highway robberies on the road between Forbes and Lambing Flat," McGuire says. "[They were] openly travelling the roads, calling at inns, homestead and huts, robbing whoever they pleased and always managing to avoid the police. This was not surprising, considering the troopers were outclassed in bushmanship and horsemanship, and received little help from the inhabitants, many of whom were sympathisers of the bushrangers."

In the course of the next two years, the newspapers attributed over 100 robberies to Hall and the various men who drifted in and out of his gang. "They were incredibly busy - a very serious work ethic among these lads," Roweth confirms. "Any number of young men would take part in a robbery or two and then disappear back to their farms. I sometimes think it's the same motivation that led many young Australians to enlist in the First World War: 'Home by Christmas, and it'll be fun. It'll be exciting'."

Part of the appeal for Hall's young recruits was the swagger he and his companions brought to everything they did. "Bushranging by this gang is evidently not followed as a a means of subsistence," declared one half-admiring editorial. "Every new success is a source of pleasure, and they are stimulated to a novelty of action from a desire to create a history. [.] Every word they say, and every thing they do, is recorded and they aspire to a name." (6)

McKenry agrees. "That's why Ben Hall's gang is sort of unique," he told me. "There certainly were people who tried to bail up mail coaches and whatever, but very few were successful and very few would have got much out of it. If you look at it in terms of how long they were at large, there weren't many who survived more than a few months. If you're successful, like a Ben Hall or a Ned Kelly, and you're well-known and you acquire enough goodwill in the community not to get dobbed in to the police, then it's a different situation."

Here's a few examples of the exploits that set Hall and his companions apart:

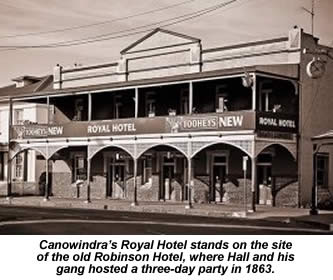

* September 26, 1863. Hall, Gilbert and O'Meally - now joined by a couple of Carcoar horse thieves named Johnny Vane and Micky Bourke - bail up Robinson's Hotel and the surrounding shops in Canowindra, a small town with just a single lawman to its name, then insist the townsfolk join them for a night's celebration. "We made a night of it at the hotel, keeping the dance going in lively measure the whole night through," Vane later told the pamphleteer Charles White. "We left the town next morning, first giving the policeman a strict caution not to give information to headquarters until the following day."

* October 3, 1863. The gang raid Bathurst, a far bigger town with a population of about 6,000. After raiding a watchmaker's shop, they take over the town's Sportsman Hotel. The police, assuming Hall and his men would have fled town straight after robbing the watchmaker, never think to look for them in Bathurst itself, leaving the gang's revels at the hotel to continue uninterrupted. "They bailed up the publican, relieved him of his cashbox and watch and then spent the next half hour in the bar yarning and buying drinks for the crowd," Peter Smith writes in his 1982 book Tracking Down the Bushrangers. "Later, they quietly slipped out of town in the direction of Caloola."

* October 12-15, 1863. The gang returns to Canowindra, this time taking the whole town over for a full three days. Once again, they make the Robinson Hotel their headquarters and forcibly invite all the town's residents to join their party there. "Little attempt was made to steal from the victims," Bill Wannan says of this raid in his 1963 book Tell 'Em I Died Game. "The hold-up was intended largely as a piece of imaginative bravado and defiance of the law." (7)

One of the the gang's hostages that day later gave his impressions of its three senior members. "Gilbert is a very jolly fellow, of slight build and thin - always laughing," he said. "O'Meally is a murderous-looking scoundrel. Ben Hall is a quiet, good-looking fellow, lame, one leg having been broken. He is the eldest of the party and the leader - I fancy about 28 years of age. They are constantly talking about their exploits and of the different temperaments of people they have 'bailed up'." (8, 9)

One of the people they held prisoner in a later raid in Wallendbeen gave journalists a vivid description of the bushrangers' appearance and differing attitudes. "Gilbert was well-dressed and his spirits very buoyant," he reported. "Hall, on the other hand, looked fagged and careworn. Both wore a number of gold chains. Hall's belt was studded with revolvers, but they could not be seen unless he threw back the folds of his poncho, which reached nearly to his heels. Gilbert, who was well-furnished with similar firearms, appeared more at ease than Hall. From the way in which he [Gilbert] moved about, there appear to have been plenty of chances of firing at him, but Hall kept his eyes shifting from one side to the other, apprehensive of being taken treacherously." (10)

So far, we've focused on the relatively innocent stage of the gang's career, when it was easy to chuckle at their exploits and poke fun at the police's hapless attempts to stop them. But there were darker strands in the tapestry too. As early as August 1863, O'Meally had killed a storekeeper called John Barnes while robbing him on the Murrumburrah road. Instead of obeying the call to hand over his bridle and saddle, Barnes spurred his horse away. O'Melly shot him in the back as he fled.

Things turned sourer still twelve days after the second Canowindra raid, when Hall and four others lay siege to Henry Keightley's place near Rockley. Keightley was an outspoken and well-connected magistrate who'd done all he could to help police catch the bushrangers, so Hall felt they had a beef to settle there. Bourke took a gutful of buckshot during that day's fight with Keightley's men and died on the scene. The rest of the gang eventually captured Keightley and his wife, taking £500 as the price of releasing them again, but it was poor compensation for losing their mate. (11)

The authorities responded to the Keightley raid by putting a £1,000 bounty on each of the remaining gang member's heads - a move which Smith calls "the first major blow against them". Less than a month later, on November 19, Vane turned himself in, figuring prison was at least better than a violent death. On that same day, O'Meally was shot dead as the remaining gang raided a Eugowra homestead. In the space of just four weeks, this seemingly invincible five-strong gang had been cut down to Gilbert and Hall alone.

The duo staged a bravura show of defiance in the last few weeks of 1863, robbing two mail coaches and carrying out what's said to be a total of 20 stick-ups in one particularly busy day. As Christmas approached, Gilbert decided he'd have a healthier future elsewhere in the colony, so he headed south to Victoria, leaving Hall to recruit some new companions to continue working the area round Forbes. One of them was a 17-year-old jockey called John Dunn.

There was another Canowindra-style binge in May 1864 - this one at a racehorse owner's home in Young - then Gilbert returned for a November mail coach robbery in Black Springs Creek, where he shot dead a police sergeant called Edmund Perry. That led to a murder warrant being issued not only on Gilbert himself, but on Hall and Dunn as well. Two months later, Dunn killed a policeman of his own, a Constable Samuel Nelson, during the gang's raid on a small hotel near Lake George. The end wouldn't be long in coming now.

Early in 1865 New South Wales legislators pushed through the Felons Apprehension Act, a measure specifically written to target Hall, Gilbert and Dunn. If the three men didn't hand themselves in at Goulburn goal by April 29, the Act said, they'd be declared outlaws, and hence removed from even the most basic of the state's protections. "As outlaws, they could be shot on sight by policeman or civilian without being called on to surrender," Smith explains. Another provision in the same Act warned that anyone found harbouring an outlaw would have all his land and property confiscated and face a prison sentence of up to 15 years.

When the three bushrangers declined to surrender themselves in time for the April 29 deadline, the legislators made good on their threat, announcing May 10 as the date their new outlaw status would take effect. Gilbert decided his best bet was to head back to Victoria, this time with Dunn accompanying him, but Hall was still reluctant to leave. He retreated to a deserted area on the Goobang Creek near Forbes, where he hoped to collect some of the money he'd stashed with a trusted sympathiser called Mick Connolly. His plan was to rest up at Connolly's place for a few days before deciding on his next move.

Unfortunately, Connolly wasn't quite as trustworthy as he seemed. Motivated by the prospect of a reward - or perhaps just by fear of the new Act's punishments - he found an excuse to go into Forbes alone, called at the police barracks there and told sub-inspector Davidson he'd find Hall's two horses in a certain gully on Connolly's patch of land. Hall would be camping out near that gully tonight, he added - and he'd be all alone.

Ned Kelly's uncle, Jack Quinn, gave his own account of Connolly's betrayal in a letter to Sydney's Truth newspaper. "When he got home, Ben asked him how Forbes was," Quinn told the paper in 1911. "He said, 'It's all on fire about you. I think you had better not stay in the house tonight'. Ben took a blanket, and went down the creek about half a mile amongst some saplings on the edge of Micky's plain. Goolang Mick brought his supper after dark." (12)

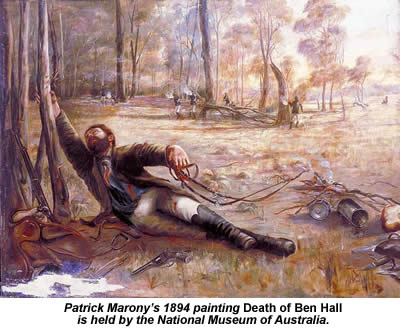

All this was on May 4. As Hall ate, Davidson's squad, helped by a native tracker called Billy Dargin, was surrounding Connolly's gully, where they found Hall's two horses but no sign of the bushranger himself. They decided to wait in ambush there till he turned up to reclaim his mounts. Davidson's sergeant, James Condell, knew Hall from earlier in his police career, and so would be able to identify him on sight. (13, 14)

"At about six o'clock next morning, I saw a man emerge from the scrub into a piece of open country and walk in the direction of the two horses," Condell later testified. "When he was about mid-way from the camp to the horses, we started in pursuit and ran about 50 yards before he observed us. He then looked up and and saw us. He turned and ran from us. Sub-inspector Davidson then called on him to stand, He looked round and still kept running. Sub-inspector Davidson then fired at him immediately afterwards. I saw Hall jump [but] he still kept running." (15)

Davidson's own testimony is broadly the same. "I called several times and ordered him to stand," he said. "I was within 40 yards of him when I levelled a double barreled gun and fired one shot. I believe I hit him, for he halted and looked back. Sergeant Condell and Billy then fired. I think they both hit him."

Back to Condell: "I levelled my rifle at [Hall], covered him full in the back and fired. I believe the shot took effect between the shoulders. After this, he rolled about and appeared very weak. The tracker then fired with a double-barreled gun and I believe hit the deceased. We called for the men stationed on the opposite side. When he saw them emerge from the scrub, he turned and ran in another direction. The men all fired. I believe most of the bullets hit him. He then ran to a cluster of timber, laid hold of a sapling and said, 'I am wounded, I am dying'. The men then fired again and he immediately rolled over."

"I noticed Hall's revolver belt fall to the ground," Davidson adds. "Hall, still holding to the sapling, gradually fell back: altogether 30 shots were fired." And finally here's Condell with the last word: "He threw out his feet convulsively once or twice and said, 'I am dying, I am dying'. We all then approached him and found he was dead. We then packed his body on a saddle and removed him to our camp - and thence to Forbes." There's a whole other ballad about their arrival there.

In his commentary track for the 2016 movie The Legend of Ben Hall, director Matthew Holmes mentions a recently-uncovered letter from Davidson to his father, written soon after the ambush. "He says Hall got a terrible riddling and that, after he [Davidson] fired the first shot and made a terrible wound on Hall's shoulder, his men just went crazy and he couldn't control them," Holmes says. "And that was a private letter, it wasn't the public record." (16)

The shooting remains controversial to this day, with campaigners pointing out that the law making Hall an outlaw was still five days shy of coming into force when police killed him. Perhaps that's why both Davidson and Condell were careful to say they'd called on his to surrender first, and opened fire only when he chose to flee instead. In any case, with their worst nuisance disposed of at last, the authorities were in no mood to quibble about niceities. Hall's death was quickly ruled a justifiable homicide and the £1,000 reward duly paid out.

Davidson got £450 and Condell £150, together with a promotion each. Their four troopers were given £80 each, leaving just £60 for Dargin and £20 for the other tracker. Mick Connolly was give £500 for his own part in the affair and has been vilified as a traitor in song and folklore ever since. (17, 18)

Notes

Just about every account of Hall's life agrees that he never killed anyone himself. "No brand of Can stamped his brow," as the ballad Brave Ben Hall puts it.

The sole dissenting voice I've found comes in a May 1865 story from the Illustrated Melbourne Post. This credits the recently-killed Hall with "two murders, twenty-two robberies with arms and thirty-two other robberies", but gives no details beyond that. When Gilbert and Dunn killed, the papers were quick to report this fact and name their victims, but there are no equivalent stories reporting a death at Hall's hands - which makes the IMP's claim suspect at best. (19)

The closest he came to taking a life seems to have been an incident on March 1, 1863, when Hall, O'Meally and their companion Patsy Daley bailed up a Police Inspector Norton on the read near Sandy Creek, taking some 15-18 shots at him in the process. "Some sharp firing ensued on both sides until Mr Norton's ammunition was all expended," the Lachlan Miner reported two days later, "the three bushrangers doing all in their power to shoot him, and one of them, Ben Hall, deliberately firing at him even after he had given himself up." The bushrangers released Norton unharmed after holding him for three or four hours and helping themselves to whichever of his possessions they fancied. Hall emerged from the incident still with no blood on his hands but, in this instance at least, it looks more like a matter of luck than judgement. (20)

The Music

You can find a live reading of Ogilvie's The Death of Ben Hall here, and two Ben Hall songs with the same title on the Spotify playlist I've called PlanetSlade Bushrangers. His life's also inspired three silent movies (all released in 1911) plus an Australian Broadcasting Company TV series in 1975 and a full-production feature film in 2016. (16)

Sources & footnotes

1) PlanetSlade telephone interview with Jason Roweth, April 2018.

2) Some of the Ben Hall ballads pick up on this idea, depicting him not just as a bandit, but as a political revolutionary too. The Ballad of Ben Hall's Gang, for example, has this verse: "'Some day on Sydney city, / We mean to pay a call, / And we'll take the whole damn country,' / Says Dunn, Gilbert and Ben Hall."

3) McGuire's memoir, Early Colonial Days, was ghosted by WH Pinkstone after a string of interviews between the two men. It's written in the first person, as if by McGuire himself. This material also appeared as a series of press article credited to McGuire, which I think preceded the book itself.

4) Pottinger was sacked from the police in February 1865 and died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound a few weeks later.

5) PlanetSlade telephone interview with Keith McKenry, April 2018. Some sources claim Hall was involved in the Eugowra robbery, others that he was not. All we can say for sure is that Pottinger wasn't able to prove it.

6) Bathurst Times, October 5, 1863. The same piece credited each member of the gang's ruling trio as "having combined the desperado and the gallant in his own person".

7) The Diverting History of John Gilbert, an 1863 ballad published in the satirical magazine Melbourne Punch, takes issue with the popular view of the bushrangers as harmless rogues, Describing this second Canowindra raid, it says: "And every stranger passing by / They took, and when they'd got him / They robbed him of his money, and / Occasionally shot him."

8) This description is quoted in Peter Smith's Tracking Down the Bushrangers (1982), but I haven't been able to trace its source any further back than that.

9) Hall broke his leg early in life while trying to tame a wild horse. It was never set properly and left him with a limp.

10) Newcastle Chronicle & Hunter River District News, April 1, 1865.

11) Burke tried to kill himself when he saw how badly he'd been shot, but it's not clear whether it was this suicide attempt or the original wound that killed him. The newspapers reported that he took two wavering shots at his own head straight after collapsing, but also that he didn't die until a little while afterwards.

12) Truth, May 21, 1911. Ned Kelly had an uncle called Jack Quinn on his mother's side of the family, who maintained a pretty lively criminal career of his own. There were other Jacks in the family too, but my money's on Ned's uncle as the one who wrote the letter.

13) An Illustrated Melbourne Post description of Hall at about this time says he was "five feet nine inches in height, of stout build and weighed about 13st 7lbs. [.] He had light brown wavy hair with a light beard which became darker as it grew under the chin."

14) Some accounts claim Dargin and Hall were old friends, saying Hall begged Dargin to shoot him dead rather than let the troopers and police do it. See my piece on The Streets of Forbes for more about this.

15) Both Condell and Davidson's testimony is taken from an inquest report in the Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser of May 9, 1865.

16) The Legend of Ben Hall (High Fliers Films, 2016). Worth seeing if you have any interest in the case. There's a second commentary track from Peter Bradley, the film's historical advisor.

17) Figures taken from the Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser of May 13, 1865.

18) Connolly's reward was paid into his bank account as five £100 installments to try and keep it secret. Word got out just the same, and one verse I've cut from the Ogilvie ballad shows him shunned by everyone in his old Forbes pub when he tries to buy them a drink: "He banned no creed and he banned no class / And he called to his friends by name / But the worst would shake his head and pass / And none would drink from the bloodstained glass/ and the goblet red with shame."

19) I've taken this quote from the 1944 Georgian House paperback Bushranging Days, which sources it to an 1865 issue of the Illustrated Melbourne Post.

20) Lachlan Miner, March 3, 1863.