Thomas Wright, a West London barrister, came home from his Lincoln's Inn chambers one evening in January 1904 to find a mob of treasure hunters wrecking his front garden. One of them had already dug down to the base of the garden railings and was busy trying to dislodge them to see if a £50 medallion had been buried beneath. Glancing up and down Westbourne Terrace, Wright could see that many of his neighbours' gardens had been invaded too. This had been going on for four days.

Thomas Wright, a West London barrister, came home from his Lincoln's Inn chambers one evening in January 1904 to find a mob of treasure hunters wrecking his front garden. One of them had already dug down to the base of the garden railings and was busy trying to dislodge them to see if a £50 medallion had been buried beneath. Glancing up and down Westbourne Terrace, Wright could see that many of his neighbours' gardens had been invaded too. This had been going on for four days.

Wright waded in, grabbed one of the ringleaders from his own garden by the collar and started dragging him towards the nearest police station. But the mob immediately closed around him, blocking Wright's path and insisting that he let the man go. When he refused, they began jostling him. Some helped Wright's captive slip out of his coat and escape, cheering him on as he fled the scene.

Even if Wright had been young and fit enough to give chase, the mob was not going to allow it. Fearing for his safety, he took refuge in the nearest house, where the owner allowed him to remain until two policemen arrived on the scene about ten minutes later. Wright gave them the captured coat, they escorted him safely to his own front door, and the night's ordeal was over.

We know all this because Wright sat down next morning and described the episode in a letter to The Times. “From early on the 10th inst., down to today, the 14th, from morning to night, and even in the night, these thoroughfares have been infested by crowds of people watching for, and finding, opportunities in digging up the private roadways and gardens in searching for the treasure,” he said.

“Westbourne Terrace and Gloucester Gardens have been most seriously damaged, and the streets are still beset with gangs of idle people bent either upon doing further mischief or enjoying the pleasure of seeing other doing it” (1) .

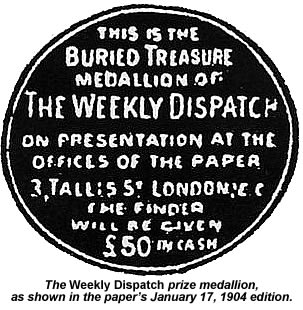

Wright's attackers were looking for one of several hundred prize medallions which a couple of Sunday newspapers had planted around the UK - most likely those from the Weekly Dispatch. The paper used its first issue of the New Year to announce it had concealed 177 treasure medallions, the most valuable of which were worth £50 apiece. Each issue would carry a series of clues pointing to the prizes' locations. That meant, of course, that anyone hoping to find one of the medallions had to buy a copy of the Dispatch first – and perhaps its special supplements too.

By January 17, the total prize money on offer had reached £2,000. Twenty £50 medallions were hidden in London, giving the capital a total of £1,000, and the rest in Manchester (£500), Reading (£50) and nine other English towns. The scheme added another £1,790 in prizes before the end of the month, bringing the total to £3,790, and stretching its reach as far afield as Leeds, Belfast, Norwich and Cardiff. Ten pounds in 1904 had about the same purchasing power as £900 has today, so even the humblest medallions were well worth finding.

Three days after Wright's letter appeared, his neighbourhood was still under assault, with big crowds of treasure hunters gathering less than half a mile from his home. At lunchtime on January 18, a 19-year-old Battersea labourer called Frederick Nurse was arrested in Blomfield Road. He had been digging at the roots of a tree there with a carpenter's gouge. When challenged by PC Ford, Nurse explained that he was “looking for the buried treasure”.

Reporting next day's proceedings against Nurse in Marylebone Magistrates' Court, The Times said there had been “hundreds” of other treasure seekers in Blomfield Road at the time, digging at the roadway and trespassing wherever they pleased. Paul Taylor, the magistrate, said substantial damage had been done to the highway by “this most unbearable nuisance” and fined Nurse 40 shillings (£2) with the alternative of a month in prison. Meanwhile, Clerkenwell magistrates were dealing with three similar offenders of their own, part of a treasure-seeking crowd big enough and rowdy enough to require the dispatch of extra police from King's Cross to control them (2) .

All over London, the story was the same. Crowds gathered outside Pentonville Prison and Islington's Fever Hospital, blocking the roads and attacking any scrap of loose ground. Hundreds of treasure seekers converged on a Bethnal Green museum and began digging there. One Shooters Hill resident said his area was “infested with gangs of roughs”. Shepherd's Bush, Clapton and Canning Town were besieged too.

By the time Nurse had his day in court, Luton and Manchester had also been hit. Luton residents seeking the town's single £10 medallion caused what councillors called “a gross disturbance” to the town in the early hours of Sunday, January 10. A week later, the Manchester Evening News found “some most extraordinary scenes” in its own city.

“From an early hour on Saturday night to late on Sunday night, various parts of the Manchester suburbs were the resort of men, women and children, people of all classes, drunk and sober, who had taken up what they thought to be the real clue to the spot where a medallion worth £25 lay hidden beneath the turf,” the MEN reported. “They seized upon vacant pieces of land and stretches of roadway, digging and delving until not a foot of the ground lay smooth.” In Blackley, it added, three hunters had arrived simultaneously at the same spot and “settled the matter by a three-cornered fight” (3).

Wherever the Dispatch's promotion touched down, hysterical treasure hunters began tearing up the public highways with knives, shovels, sticks and any other implement that came to hand. If they took it into their head to dig up a private garden or vandalise the local park, they went right ahead and did so. Anyone who protested was bullied into submission, just as Wright had been. The promotion was less than three weeks old, and already causing chaos.