“Often a dealer, unable to get a fast bid, would knock down a complete lot to me, calling out before anyone else could make a bid, 'Thirty bob, Mr Jackson - all right?’ The greatest fun was getting the stuff home and discovering what was in the books and portfolios.”

“Often a dealer, unable to get a fast bid, would knock down a complete lot to me, calling out before anyone else could make a bid, 'Thirty bob, Mr Jackson - all right?’ The greatest fun was getting the stuff home and discovering what was in the books and portfolios.”

- Peter Jackson, Illustrated London News (1991).

“When his series London is Stranger than Fiction was published in book form the demand was tremendous. The book was sent all over the world to be cherished by exiled Londoners wherever they were.”

- Introduction to Jackson’s London Explorer collection (1953).

Earthquake pills. They’re something you only see in old Roadrunner cartoons, surely?

Nope. Pills like these were actually sold on the streets of London as long ago as 1750, and returned to public attention 200 years later when the cartoonist Peter Jackson included them in his newspaper strip about the capital’s weird and wonderful history. London Is Stranger Than Fiction, as Jackson called his strip, ran every week in The Evening News for over two years and was swiftly followed by his London Explorer series there. That’s 164 strips altogether, each one still providing a fascinating source of facts and trivia for the city’s residents today.

Jackson covers the earthquake pills in his strip of March 8, 1950, marking the exact anniversary of a 1750 earth tremor which startled many Londoners into fleeing the city. A mad guardsman’s prophecy of bigger shocks to come caused enough fuss to set people clamouring for what Georgian spivs called “pills good against earthquakes”. Jackson illustrates this item by drawing a snooty-looking conman peddling these dubious tablets in Trafalgar Square. There’s a looser, more cartoony style to the art as he moves from the panel’s realistic background to rendering this chap’s face – a trick he often used when it was the absurdity of a particular episode he wanted to stress.

As with all Jackson’s work, he’d researched the pills story with great care, tracing second-hand accounts back to their ultimate source in an 18th century issue of Tatler. His drawing is equally meticulous, ensuring the street peddler wears authentic 1750s clothes, and placing a very recognizable St Martin-in-the-Fields behind him to establish location. This item’s just one of four he finds room for in the March 8 strip, the others covering the unique hats worn by Billingsgate fish porters, a remarkable tomb at Bunhill Fields and where to find the West End’s clock in a barrel. The clock item’s phrased as one of his weekly quiz questions, its answer left for the paper's subs to add in upside-down print just below the strip itself. (1)

I first came across Jackson’s work in December 2021, when I spotted a vintage LISTF collection on a stall selling used books in Islington. I handed over my cash, brought the book home, and devoured it that afternoon. Every strip brought more of Jackson’s characteristically quirky revelations: the Smithfield statue with a real wedding ring welded to its hand; the one-legged man hired to demonstrate the Tube’s first escalator; the eminent London doctor who tried to shoot out one of his own teeth. I learned for the first time of Jenny Diver, the queen of Covent Garden’s pickpockets, discovered why Charles I’s Whitehall statue had to be buried in a Holborn garden and chuckled at Jackson’s depiction of a thieves’ college that once thrived near London Bridge. From time to time, I’d even find a story there I’d written about myself for PlanetSlade, such as the backdoor consecration methods George Whitefield resorted to at his Tottenham Court Road chapel. There’s Whitefield himself in one of Jackson’s November 1949 strips, sleeves rolled up and busy scattering his stolen earth. (2)

These are just the sort of London stories I love. Stir in my fascination with cartooning, and it’s no surprise I was soon scouring the web to find Jackson’s two other 1950s collections. These strips were so far up my street they might as well have moved into the spare room. Perfect fodder for a PlanetSlade essay, in fact…

Ripley’s

Believe It or Not is a global operation today, with 32 dedicated museums in nine different countries, dozens of books on sale and a long history of hit TV shows. When it began life in 1918, though, it was just a humble newspaper strip in the New York Globe. Robert Ripley switched its initial focus from sports stories to oddities of all kinds the following year and, in 1929, struck a syndication deal with King Features which extended the strip’s reach enormously. At its peak, it would hit a worldwide readership of some 80 million people.

In 1948, London’s Evening News decided it wanted a similar feature of its own, and announced it was looking for a cartoonist to produce a regular strip based on the strangest stories to be found in London’s past. Peter Jackson, then just 26 years old, was one of those who applied. Steve Holland, an expert on UK comics, filled me in on the cartoonist’s background. “He’d studied at Willesden School of Art and found work with United International Features, which created adaptations of classic novels for newspaper serialization,” Holland told me. “He was from Brighton and didn’t know much about London, but the Evening News hired him for a three week trial period on the strength of his drawings.” (3)

Jackson had funded his two years’ study at Willesden with his demobilization grant from wartime service as an Air Raid Warden and also studied with the great Italian war artist Fortunio Matania. The classic novel adaptations he’d drawn immediately after the war included Ivanhoe, The Three Musketeers and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, so he was already comfortable with researching and accurately rendering the past. The new Evening News strip debuted on January 12, 1949, and was given a weekly slot there after just three outings. It seems to have arrived fully-formed – perhaps because it had such a clear model in Ripley’s – and would retain exactly the same style until March 1951.

“When I started I knew nothing about London,” Jackson later told the Fulham Chronicle. “I ransacked the shelves of public libraries to learn about the strange and curious in London. Then they put a piece in the paper asking people to send in their London stories and I was given the job of sorting through them.” Useful as that source was, he soon learned not to take any reader’s story on faith alone. Desperate for a quiz question one week, he dug out a letter claiming the Cenotaph was in Parliament Street rather than Whitehall, and duly repeated this “fact” in print. It wasn’t till after the paper was already on sale that he discovered it was nonsense, and had to shame-facedly admit his mistake. (4)

Jackson may have been ignorant about London when he started LISTF, but he soon became obsessed with the city. The strip’s 1951 collection has an introduction describing his Kilburn studio’s library of books about London’s past, its stacks of old newspapers and illustrated volumes on architecture and costume. “He will work for days on research into a single cartoon incident, poring over old books in the British Museum or following a trail on an ancient map through the labyrinth of modern London,” it continues. By 1953, when a second collection of his Evening News strips appeared, Jackson’s accumulation of London material had grown into what the book calls “one of the most comprehensive private collections of London lore” to be found anywhere in the world. “There is just room for a desk, a drawing board and the artist himself,” the piece says of Jackson’s studio. “[He is] a slim young man with longish hair, heavy horn-rimmed spectacles, the absorbed air of a student and abounding enthusiasm for his subject.” (5, 6)

Holland places Jackson in the European school of “clear line” artists, a style most familiar to British readers from Hergé’s Tintin books. A key feature of this school is its use of detailed realistic backgrounds populated by people drawn in a simpler and more cartoony way. “Jackson was a superb illustrator with a huge reference library of historical images, so his drawings are grounded in reality,” Holland told me. “His use of cartoony figures against a realistic background keeps the images lively. The quirkiness of the strip and the combination of research and skilful illustration means it can still be enjoyed today. It’s an amazing historical record of the city.” (7)

Matt Brown, editor at large of the Londonist website, agrees. “His work was inspirational to me,” Brown says. “His eye for a London curiosity and the flair and joy with which he shared them validated my own interests – it was OK to get excited over a hoary bollard or a peculiar old plaque. People have been describing the everyday oddities of London for centuries but Jackson was one of the first, and best, to bring them to life in illustrations. We regularly run Jacksonesque pieces [on Londonist.com] and our Urban Oddities Facebook group has grown to 133,000 members. Most of those people will never have heard of Peter Jackson, but they share his enthusiasm and curiosity for the miniature wonders of London’s built environment.” (8)

Like Charles Dickens before him, Jackson often found inspiration for his work simply by wandering round London to see what caught his eye. Spotting a fruit stand beneath the gateway at Lincoln’s Inn, for example, led him first to question its owner and then to study this Inn of Court’s 17th century records. These revealed that the rights to run a fruit stand there had first been granted around 1614 – a nugget of information which Jackson duly passed on to his readers in a September 1949 strip. “It must be the oldest stall in London,” he told reporters a few years later.

Jackson kept up an unbroken run of LISTF strips in the Evening News until March 28, 1951, drawing every one of those 112 strips himself and never missing a weekly deadline. He then decided to give the format a tweak. Retitling the strip London Explorer, he started devoting each week’s entry to a single neighbourhood, such as Soho, Cheapside or Battersea. The new strips were a little more cluttered than the old ones had been, often including seven or eight items a week against LISTF’s four or five. Another new element was the small walking map which Jackson drew into every London Explorer strip, allowing readers to stroll in his footsteps from one notable spot to the next.

By 1953, when his second collection was published, Jackson had added 50 London Explorer strips to his Evening News run, the first two of which looked at Mayfair and Hyde Park Corner. The mix of items for these reflected the same fascination for forgotten history which had always fuelled LISTF. In the Mayfair strip, for example, we learn that the man who’d soon become George IV was once mugged as he left a Berkeley Street brothel. Hyde Park Corner’s strip reveals that the Artillery Museum’s stone howitzer is angled to rain its shells on the Somme.

Jackson’s next change to the strip was a more radical one, swapping its horizontal shape for a portrait box which once again gave his art room to breathe. This transformation both broadened and narrowed his focus, moving beyond London to include the surrounding counties but often limiting the strip’s subject to a single building per week.

Now titled Somewhere To Go, this strip – or, more accurately, this panel - got an Evening News collection of its own in 1958, which contains 64 cartoons and a good deal of supporting text. To judge by this volume, well over half the buildings Jackson chose for STG were historic pubs, such as The Ostrich in Buckinghamshire (murderous 17th century landlord), Aldgate’s Hoop & Grapes (oldest pub in London) and The Leather Bottle in Kent (appears in The Pickwick Papers). Stately homes figure pretty regularly too, giving Jackson the chance to discuss subjects like Catherine Howard’s imprisonment at Syon House in Middlesex and a sinister Sussex portrait of Sir Ralph Assheton restraining his wife. (9, 10)

I’ve concentrated on Jackson’s Evening News cartoons so far, but these were only one small part of his career. He’d often write prose pieces for the paper and regularly supplied spot illustrations for other contributors’ articles too. “In the 1950s, he drew illustrations for Mickey Mouse Weekly, which led to him doing comic strips,” Holland explains. “Features in Junior Express Weekly led to him drawing Mark Fury, an adventurer in historical London, there and later to work for the Eagle.”

I’ve concentrated on Jackson’s Evening News cartoons so far, but these were only one small part of his career. He’d often write prose pieces for the paper and regularly supplied spot illustrations for other contributors’ articles too. “In the 1950s, he drew illustrations for Mickey Mouse Weekly, which led to him doing comic strips,” Holland explains. “Features in Junior Express Weekly led to him drawing Mark Fury, an adventurer in historical London, there and later to work for the Eagle.”

The Eagle, home to Dan Dare, was Britain’s most prestigious comic of the 1950s, and it’s a tribute to Jackson’s skill that he was allowed to take over a back cover feature there from the great Frank Bellamy. This was The Travels of Marco Polo, which Jackson followed up by drawing Gordon of Khartoum in the same high-profile slot. A couple of years later, in 1962, he moved to the newly-launched educational comic Look and Learn, beginning a steady stream of work there which would keep him busy for the next 20 years.

Laurence Heyworth, who bought Look and Learn’s image library in 2004, lists Jackson’s contributions to the first issue as launching its back cover serial The Dover Road and providing a cutaway view of the Houses of Parliament for the centre spread. “He was also the main contributor of historical illustrations for Look and Learn’s junior publication Treasure, which launched in 1963,” Heyworth writes. The picture library he now runs contains over 2,000 of Jackson’s images, ranging from one-off paintings showing scenes like Christopher Wren supervising the building of St Paul’s to many examples of the three newspaper strips we’ve already discussed. (11)

Holland joined Look and Learn about a year after Heyworth took over, and the two men worked together in preparing and publishing a new book collecting all Jackson’s LISTF and London Explorer strips between a single set of covers. It’s the first time this work had been back in print and available outside the collector’s market for over 50 years. “London lore is a subject of perennial fascination,” Heyworth told me. “The best stories don’t change. What is unique about the strips is that they combine historical knowledge with an astonishing visual imagination. Peter Jackson is one of the greatest historical illustrators of all time.” (12)

“The book came about because Laurence’s interest in history led him to pick up copies of the old collections,” adds Holland. “I borrowed them from the office, became a fan and floated the idea of reprinting Jackson’s books. Laurence sought out the copyright holders – Associated Newspapers – and we got permission to do the book. The strips were taken from the printed books as the original artwork had long disappeared.”

A few days after buying the original LISTF book, I began using it to guide my daily walks. Often it led me to landmarks I’d walked past a hundred times before without ever suspecting the tales that lay behind them.

A few days after buying the original LISTF book, I began using it to guide my daily walks. Often it led me to landmarks I’d walked past a hundred times before without ever suspecting the tales that lay behind them.

Jackson was the perfect companion for these walks, sketching in the forgotten secrets of a familiar street name at one moment, then explaining the significance of a neglected statue the next. Not everything he depicted survives in modern London, of course – the Shoreditch stocks Jackson records in St Leonard’s churchyard have vanished for a start – but a great deal still does. Whether you choose to follow one of Jackson’s own maps or to patch together a route of your own, his work remains as irresistible as ever.

When I spoke to Matt Brown for this piece, I discovered he’d used Jackson’s books in exactly the same way when he first snapped them up five years ago. “I keep a Google map of unusual London sights I’ve yet to visit, and it got a rash of new points after I read Jackson’s books,” he told me. “A particularly joyous discovery was the Jelling Stone near Regent’s Park [which replicates an ancient Danish monument]. I’d lived within a 15 minute walk of this stone for about a decade and had no idea of its existence. Jackson’s book turned me on to something amazing in my own neighbourhood. What a joy!”

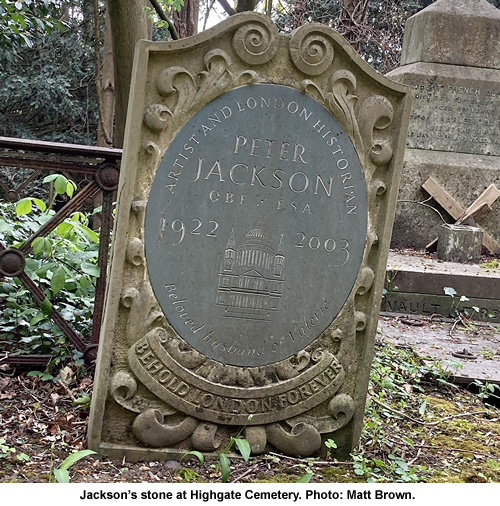

Outside his work as a journalist, Jackson teamed with his old Evening News colleague Felix Barker to produce illustrated prose books on London history, presenting items such as old maps and theatric ephemera to a new audience. His personal library of old London documents and prints continued to grow, and became an invaluable resource for the city’s scholars and publishers. He was elected chairman of the London Topographical Society in 1974, helped found the Ephemera Society a year later – which is now chaired by his widow, Valerie - and became a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1980. He died in May 2003, aged 81, and is buried in Highgate cemetery beneath a stone whose inscription could hardly be more perfect: “Behold London forever”.

The 2012 reprint volume collecting Jackson’s strips is titled London Is Stranger Than Fiction and can be bought direct from Steve Holland here. Look and Learn has an archive of over 2,000 Jackson images and strips you can view online.

Sources & footnotes

1) The issue in question was Tatler #240, where Joseph Addison mentions “an impudent mountebank who sold pills which (as he told the country people) were very good against an earthquake”.

2) For the full story of Whitefield’s work at Tottenham Court Road, see this PlanetSlade essay.

3) E-mail to author, January 2022.

4) Fulham Chronicle, December 30, 1955.

5) London Is Stranger Than Fiction, by Peter Jackson (Associated Newspapers, 1951).

6) London Explorer, by Peter Jackson (Associated Newspapers, 1953).

7) Where the item demanded a more respectful tone, Jackson’s drew his subject’s faces far more realistically. His portraits of ordinary working Londoners are a good example.

8) E-mail to author, January 2022. Visit the Londonist website here.

9) Somewhere To Go’s collection was published by Associated Newspapers in 1958.

10) The portrait, which Jackson sketches in his Parham House strip, shows Assheton holding his wife by the hair, his right foot firmly placed on the hem of her gown. “The unhappy lady ran away from her husband but he caught her and had this portrait painted,” Jackson explains.

11) London Is Stranger Than Fiction, by Peter Jackson (Look and Learn, 2012).

12) E-mail to author, January 2022.