"Believed to have become suddenly insane, Charles Lawson, 42, who lived near Germanton in Stokes County, Christmas Day killed his wife, Fannie, 38, and six of his seven children and then committed suicide."

- Twin-City Sentinel, December 26, 1929.

"Believed to have become suddenly insane, Charles Lawson, 42, who lived near Germanton in Stokes County, Christmas Day killed his wife, Fannie, 38, and six of his seven children and then committed suicide."

- Twin-City Sentinel, December 26, 1929.

"Immersed in the clotted blood on the living room floor, where the five bodies were found, was a little Christmas poem. Most of its words had been blotted out by the red stain oozing over it but the large number of curiosity seekers who passed through the death chamber today could plainly make out the words 'Santa Claus'."

- Statesville Record & Landmark, December 30, 1929.

The Lawson family massacre of 1929 left enough blood on Charlie Lawson's cabin floor for neighbours to scoop it up with a coal shovel. Sixty years later, the author Trudy Smith, who's produced two books about the case, met a reader whose ancestor had visited the cabin soon after the killings. "Their family still had a jar which contained Fannie's blood, scooped up from the edge of the porch as a souvenir," she recalled.

People have always wanted to take a little of the Lawson murders home with them. Even the dogwood tree Charlie leaned against as he took his own life was stripped bare within a few hours of his body's discovery. "They wanted a piece of this terrible event," local historian Chad Tucker said in 2006. "They wanted something from this farm to keep. To say, 'I've been there'." Charlie's guns, the bricks from his demolished cabin's old chimney, even the raisins from a cake Marie Lawson baked a few hours before her death, have all become collector's items for those with an interest in the case. Like that jar of Fannie's blood, these items are passed from one generation to the next in parts of North Carolina and treated as treasured family heirlooms.

It's easy to see why these particular murders sparked such fascination. First, there's the fact that Charlie Lawson slaughtered his family on Christmas Day, a date guaranteed to add extra poignancy to any murder. He was a father killing his own children, which takes things up another notch, and did so when three of those children were under five years old - the youngest just four months. Then there's the odd mixture of brutality and tenderness he showed, bludgeoning the infants to death one minute and lovingly placing pillows beneath their shattered skulls the next. Although incest, poverty and a brain injury have all been put forward as possible explanations for the slaughter, we'll never really know what made Charlie do it.

Songwriters and poets fell on the story with glee. The most significant was Walter "Kid" Smith, a singer in the same North Carolina musical scene which produced the banjo legend Charlie Poole and his fiddle player Posey Rorer. Smith crafted the Boxing Day press reports into the ballad verses we know today and recorded them with Rorer's new band The Carolina Buddies in March 1930. Murder Of The Lawson Family, as Smith called his ballad, gave Columbia Records a big topical hit. When Arthur Lawson, Charlie's one surviving child, found grief overwhelming him in later life, it's said he would lock himself away with a bottle of whiskey and play that record over and over again.

Dave Alvin, late of The Blasters and now one of our greatest Americana songwriters, included Murder Of The Lawson Family on his 2000 album Public Domain, putting a melody he borrowed from an old English folk song to Smith's original lyrics. "Most murder ballads tend to be about one person killing another, or maybe one person killing two other people," Alvin told me. "In this case, it's a whole family. There's usually an innocent in a murder ballad, but this was an innocent family. And there's little justification given for it. It's left to the listener to decide. Was it economics? Was it insanity? Why did this guy kill his family? So that mystery gives it some power.

"It's the murder of innocent children, which is pretty intense. And then it has that final verse, which is kind of sentimentally sweet but at the same time gives the whole scene some kind of redemption."

"I knew just the verse he had in mind:

They all were buried in a crowded grave,

While the angels watched above,

"Come home, come home, my little ones.

To a land of peace and love".

Everyone the Lawsons had known came to see their seven coffins lowered into that crowded grave at Germanton's Browder Cemetery on December 27, 1929. Their grief was both genuine and deeply-felt, but we can't say the same for the 5,000 outsiders who also packed the cemetery that day. Photographs from the occasion show a crowd as tightly packed as that at any rock festival and we have reports of people clambering into the trees surrounding the tiny graveyard to secure a better view. These people were drawn by nothing more than a prurient curiosity about the case, which had filled front pages in North Carolina and the surrounding states since the first reports emerged on Boxing Day morning. Now they wanted to see the bodies for themselves.

"From hillside and valley, from hamlet and city they gathered," the Winston-Salem Journal reported. "For three miles along the road, cars were parked, while men and women, many with babies in their arms, made their way through the mud to the cemetery. There they crammed and jammed to get a glimpse of the seven caskets and tuned their ears to hear the tributes paid."

Many of those visiting the graveyard also took the opportunity to call at the Lawsons' cabin a mile away and gawp at the blood still coating its floorboards. Charlie's brother Marion knew that Arthur, then just 16, would need money to keep up the mortgage payments on Charlie's land and these ghoulish visitors gave him an idea. Within ten days of the massacre, he had the cabin securely fenced off and began running newspaper ads for the 25c tours he planned to offer there.

At their peak, these tours pulled in as many as 500 people a day - many of whom pocketed a raisin from the surface of Marie's cake or some other small keepsake before leaving. Tucker believes that, if Marion had allowed people to visit the cabin without the fence and the guides to keep them in some kind of order, there wouldn't have been a stick of furniture left behind. "You'd have started to see anything that could be removed quickly gone," he told the film-maker Matt Hodges.

When the family's belongings were auctioned at the end of January 1930, it was the murder weapons themselves which ignited the crowd. "The shotguns used to slay the seven members of his family attracted the greatest interest and went under rapid- fire bidding," the SR&L reported. "Other articles that held intimate connection with the Christmas Day tragedy also brought favorable prices under the bidding of curiosity-seekers."

Later that year, Arthur joined the tent show exhibition of Lawson family memorabilia which Marion had put together for Mount Airy's county show. "They took the crib and pieces of furniture out and exhibited it at the fairs for people to see," Lawson family researcher Patrick Boyles told me. Other accounts say Marie's cake, the stove it was baked in and at least one of Charlie's guns were also exhibited at the tent shows, with a barker stationed out front to summon in the crowds.

The song's history is intertwined with the case's early tourist trade too. Walter Smith would sometimes lecture to tour groups at the cabin, topping off his talk with a solo performance of The Carolina Buddies' hit song. Both Wesley Wall's poem The Lawson Tragedy and Elbert Puckett's Song Of The Lawson Family Murders - recently given an excellent musical setting by Lauren Myers - started life on the souvenir leaflets sold on Lawson cabin tours and at the tent show's county fair appearances.

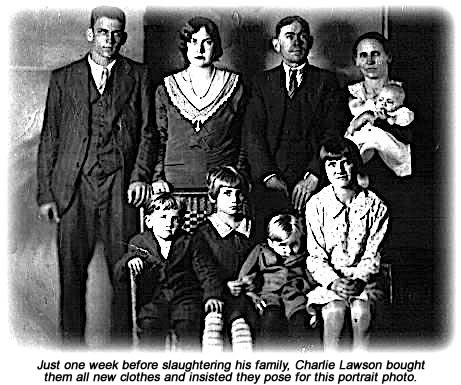

For all this frantic commercial activity, however, the most striking souvenir of all remains the one Charlie himself provided a week before the murders. That's when he took the whole family for an outing to Winston-Salem, bought them all new clothes and insisted they have a family portrait taken by the town photographer. A few days later, that photo would be on the front page of newspapers all over America, showing Charlie flanked by Fannie and Marie as he stares down the camera with a firm, patriarchal glare. "He left a message for everybody," Fannie's great niece Evelyn Hicks told Hodges. "'It's my family and I can do what I want with them'."