“For half an hour, I had been skirmishing in and out of Aldwych and along Kingsway, through the densest crowd I have ever encountered since I became a Missing Man. It stretched all the way from Holborn to the Strand and beyond; it overflowed into all the side streets; it eddied and swirled in one vast mass under Bush House, Shell Corner and the Air Ministry. It chased ‘doubles’ this way and that, who endured their sudden and surprising publicity with typical London sangfroid and good humour. Everyone was smiling and laughing.”

“For half an hour, I had been skirmishing in and out of Aldwych and along Kingsway, through the densest crowd I have ever encountered since I became a Missing Man. It stretched all the way from Holborn to the Strand and beyond; it overflowed into all the side streets; it eddied and swirled in one vast mass under Bush House, Shell Corner and the Air Ministry. It chased ‘doubles’ this way and that, who endured their sudden and surprising publicity with typical London sangfroid and good humour. Everyone was smiling and laughing.”

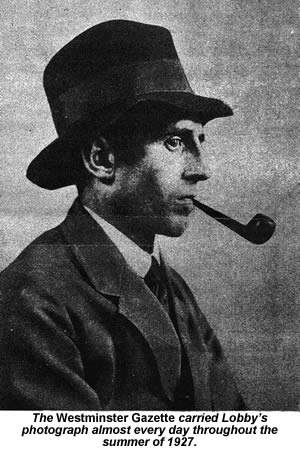

- Lobby Lud, Westminster Gazette, September 16, 1927.

It's Mr Henderson's friend I feel sorry for. This poor fellow, wandering innocently round South London's Elephant & Castle district one rainy Tuesday afternoon, was challenged 20 times in the space of an hour by Londoners determined to claim the Westminster Gazette's cash prize. They had mistaken him for Lobby Lud, the paper's “mystery man”, who it dispatched to a different London neighbourhood each day, printing his photograph and description in the paper and challenging readers to spot him as he followed his published rounds. Anyone who looked even vaguely like Lobby found themselves chased relentlessly by Gazette readers, who often refused to believe their most vehement denials.

Henderson, who detailed his own adventures in a letter to the Gazette next day, does not give us his friend's name. But we can make an intelligent guess that he must have been about 5 feet 3 inches tall, aged about 35, and clean-shaven, with dark hair and perhaps a mole on his right cheek. That's the description of Lobby which the paper regularly gave its readers, printing the details beneath a profile photograph of a dapper young man in a suit and tie, wearing a felt fedora and with a pipe clenched between his teeth. Henderson's friend may not have looked precisely like that, but the resemblance was evidently close enough to make his passage through Elephant & Castle a trying one.

“We had no sooner taken shelter from the rain under the canopy of a tobacconist's shop when four persons took up their positions near us and openly stared at my friend,” Henderson says. “Realising it was a case of mistaken identity, we crossed the road to the doorway of a large store. We were presently joined by a youth who had followed us. He was trembling with excitement and asked: ‘Are you Mr Lobby Lud?’ The youth was not satisfied he had made a mistake, for he followed us about for the remainder of the time we were in the vicinity.” (1)

The two men tried to escape by boarding a 4A bus for the City, not knowing that was one of the routes the Gazette had advertised Lobby would ride that day. There were immediate cries of “There he is!” from four girls inside the bus, so Henderson and friend fled to the upper deck. “They followed us to the top of the bus,” he reports. “But, although they and the rest of the passengers were satisfied that Lobby Lud was amongst them, they could not summon up enough courage to challenge my friend. A smart youth who boarded the bus at Blackfriars Bridge, however, challenged my friend whereupon, despite the negative reply given, two other challenges, more comprehensive, were delivered.

“We left the bus as it was going up Ludgate Hill, and turned into Amen Court. We glanced round in time to find our fellow passengers on the bus in full chase. So we took to our heels and were soon back to the common ground after a very eventful hour.”

Henderson's companion was not the only Lobby lookalike having trouble that day. Mr H Campbell's business took him to Brixton - another of Lobby's advertised stops - where he found a huge crowd waiting. “The next minute, someone slapped me on the shoulder and said ‘You are Lobby Lud. I claim the Westminster Gazette prize’,” he says. “Later, I was challenged five times and, outside the Bon Marche, two young women and a man made a run for me. I decided to go and drown my sorrows in a café, and dash it if I wasn't challenged there too.”

While all this was going on, the real Lobby was visiting Camden Town Tube station, Brixton's branch of Woolworth's and Elephant & Castle's Express Dairy, but reports not a single challenge. The crowds, however, were gratifying. “I could hardly move about the Elephant for the Lobby hunters who packed every pavement and overflowed across the roads,” he says. “All seaside records were broken.”

Lobby

had started his career as a hunted man six weeks earlier, 112 miles north east of London in the seaside resort of Great Yarmouth. The Gazette launched him on the world in its July 30, 1927, edition, renaming its reporter Willy Chinn after the telegraph address used by its Lobby correspondents at Ludgate Circus. The paper printed Lobby's trademark photograph for the first time, gave a brief description of his appearance and listed the clothes he'd been wearing when last seen. He'd be touring Britain's seaside resorts throughout the summer, it announced, starting with a Bank Holiday visit to Great Yarmouth on Monday, August 1.

Any Gazette reader with a copy of that day's paper who challenged him with the precise words “You are Mr Lobby Lud - I claim the Westminster Gazette prize”, would win £50. That prize would climb to £100 if Lobby remained undetected for one week, £150 after two weeks, and £200 after three weeks. Two days later, this was amended to say that only the first successful challenger each day would get a prize, but otherwise the competition's core rules remained unchanged.

In this first shaping of the idea, the Gazette presented Lobby as a fugitive, casting its readers as the pursuing detectives. The £50 was described as a “reward” for their “detection” of what the paper called “a Missing Man”.

“Now and again, the newspapers report the disappearance of well-known persons,” it continued. “It is noteworthy that - despite the published details concerning the missing individual - he or she sometimes manages to avoid detection for a considerable time, even when the period of disappearance is spent amid surroundings much frequented by the general public. [...] The most amazing case of the kind in recent years was the disappearance of the novelist Mrs Agatha Christie.” (2)