"How easy it is to picture the very womb of hell agape to receive

the bloodthirsty Bud Stone. [.] Pluto himself would

have to look to his laurels."

"How easy it is to picture the very womb of hell agape to receive

the bloodthirsty Bud Stone. [.] Pluto himself would

have to look to his laurels."

- Newspaperman Charles Sefrit, writing in 1894.

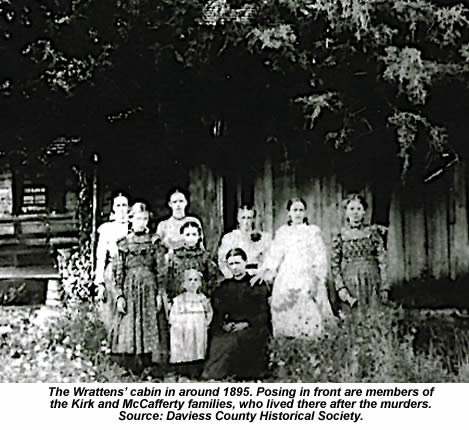

The Wrattens' family home was a wooden cabin surrounded by trees near Glendale in Daviess County Indiana. It stood about nine miles south-east of Washington, the county seat.

Living there were Denson Wratten, the sickly head of the family, his wife Ada, and their children Ethel, Stella and Henry. Also living in the cabin was Denson's elderly mother Elizabeth Wratten, a Civil War widow who still received a pension from her late husband's death.

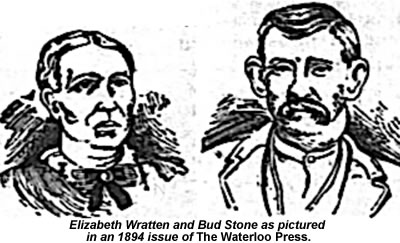

James Stone, known as "Bud", lived nearby with his wife Cecilia, and he knew the Wrattens well. Stone was a farmer, aged 42, and five feet nine inches tall with prominent ears, a walrus moustache and a bulging, blood-filled lump on the left side of his neck. Like everyone else in the area, he'd heard rumours that Elizabeth Wratten had amassed considerable savings and kept that money hidden somewhere in the family's cabin. It was said to be as much as $2,000 - a sum worth close to $60,000 today.

On Monday, September 18, 1893, the night of the murders, Cecilia woke to find her husband no longer in bed but out in their yard, where she heard him addressing someone. When he returned and she asked him who he'd been talking to, he said it was the dog. Stone told her he was suffering from an aching tooth and was heading over to Glendale to get it pulled. He left about ten that night, taking with him both his corn knife and a cooper's adz, which he hung from his suspenders with its short handle dangling against his leg. (1)

Reaching the Wrattens' cabin, Stone peered in through the window and saw Ada giving her husband some medicine as he lay in bed. Denson was very sick with typhoid fever and relied on his wife for everything. Stone could see the couple's three sleeping children in the same room, but no sign of the old lady.

This description of what came next is taken from the Indianapolis Journal of February 16, 1894, which based its account on Stone's own confession and the evidence of the crime scene:

"Nerving himself for the awful work, Stone approached the back door and knocked. Young Mrs Wratten [Ada] responded, and when she opened the door he asked her if she had anything that would be good for the toothache. She said she had a 'pain killer' and turned to get it.

"When she returned with the medicine Stone struck her point blank in the face with the corn knife, and as the woman screamed he rained blows with the deadly weapon on her face and neck, felling her to the floor. Leaping over her body, he rushed to the room in which the sick man and his children lay.

"Ethel rose on her elbow and cried: 'Bud Stone what are you doing here?' Grasping the adz, he dealt her a blow on the forehead that crushed her skull and, turning to his neighbor [Denson] who had opened his eyes dreamily aroused in his weakness at the unusual noise, he embedded the pole of the adz in his brain. He then dropped the adz and almost severed Wratten's head with several vicious blows.

"The baby was next attacked. Pulling it from its cradle, he dispatched it with one blow across the back side of its head, cleaving the skull. His bloody work well begun, the fiend leaped at Stella who had tried to escape, and she was soon writhing in her blood on the floor.

"He then tried the door leading to the room of the old lady. It had been made fast by her on hearing the struggle in her son's bed room. Stone then rushed from the house, and bursting open a window opening out on a porch, he stepped through. The old woman met him and a terrible fight ensued in the dark. Stone showered blows on the grandmother, cutting off both arms at the wrists as she attempted to protect herself. She finally fell out of weakness and loss of blood, when Stone easily finished her.

"Striking a light, Stone beheld his ghastly work, and while he had intended searching for the money that had led him to the slaughter, he says his heart failed him and he retreated through the window. When again on the outside, he thought he might not have completed his work - that some of his victims might yet be living. He then entered the slaughter pen and found Denson Wratten moving his head back and forth. Flying at him, a blow was dealt across the forehead and a quiver told him his work was complete." (2)

Convinced everyone must now be dead but still afraid to search for the money, Stone fled. Passing through the woods on his way home, he hid the bloody corn knife and adz under a log and threw a few leaves over them. He got home about 2 o'clock on Tuesday morning. A few hours later, Cecilia was fixing breakfast when she saw her husband washing blood from his shirt at the farm's spring. When she asked him where the blood had come from he claimed it was from the tooth he'd had pulled last night.

Straight after breakfast, Stone announced he was going to take a walk over to the Wrattens' cabin to see how Denton was faring with his illness. He took his young son with him, who was terrified at what he saw. "Stone's child realized that a murderer had been abroad and begged his father to leave the place," reports the Indianapolis Star. "Stone did not leave until he had convinced himself that no-one of the Wrattens would ever be able to tell the story. He did not realise then that little Ethel was not dead." (3)

Stone took his son back home, then rode into Washington on horseback to report he'd found all six members of the Wratten family murdered at their cabin with no clue to the killer's identity. "The city was shocked as never before," the Indianapolis Journal tells us. "Sheriff Leming telegraphed to Seymour for Carter's bloodhounds and the dogs arrived next morning. In the meanwhile, thousands of persons hurried to the scene of the tragedy." (4)

Stone took his son back home, then rode into Washington on horseback to report he'd found all six members of the Wratten family murdered at their cabin with no clue to the killer's identity. "The city was shocked as never before," the Indianapolis Journal tells us. "Sheriff Leming telegraphed to Seymour for Carter's bloodhounds and the dogs arrived next morning. In the meanwhile, thousands of persons hurried to the scene of the tragedy." (4)

Two of those people were Denton's cousin Isabelle Wratten and her daughter Sula Mae, who lived together just five miles from the murder scene. I spoke to Isabelle's descendent Janet Potts while researching this piece. "My grandmother Sula Mae told me she used to play with the Wratten children," Potts told me. "When they were murdered, her mom took her over to the house where the bodies were. People were touring the house and women were fainting at the sight. Apparently, Stone hid the axe and knife he used on my great grandfather's property."

If the visitors hoped for a gory spectacle, they weren't disappointed. Here's the Indianapolis Journal again:

"In the back door lay the body of Ada Wratten, Denson Wratten's wife, mutilated in a horrible manner. In an adjoining room was the body of Mr Wratten, lying on the bed with his hands crossed on his breast and a depression in the forehead as if made with the pole of a hatchet. His body was rigid in death. His face was also horribly lacerated.

"Near a little cradle lay the body of the baby Henry, aged three years, the head of the infant bearing a cut six inches in length. On a small couch in the same room lay Ethel Wratten, aged eleven. In her forehead was a depression similar to the wound on her father's head. Examination showed the girl to be in a comatose condition. Between the couch and the father's bed the mangled body of Stella Wratten, aged nine, lay.

"The most revolting scene was in the room that had been the apartment of Denson Wratten's mother, Mrs Elizabeth Wratten. She was hacked almost beyond recognition. Both arms were cut off. The face was cut to shreds and the breast horribly mutilated. Her body was soaked in blood, the carpet bedding curtains and furniture spattered with gore."

The Indianapolis Star adds that Elizabeth's room showed evidence of a titanic struggle between her and the man who killed her. "The furniture was broken and upset and bloody fingerprints were to be found in every section of the room," it says. Stone later confirmed this, telling police the old woman had "fought like hell".

Robert Swanagen and his wife, another of the local families, took Ethel Wratten in, hoping she could be nursed back to health and reveal who'd massacred her family. Despite the best care they could provide - including a trepanation at one point - she remained stubbornly unconscious.

Stone assisted at the Wratten family's funeral, acting as a pallbearer and weeping conspicuously as their coffins were lowered into the ground. He also did all he could to convince people he was joining enthusiastically in the search for their killer. When Carter's bloodhounds arrived in town, they led their handlers directly to Stone's door and, in the words of one paper, "attacked him furiously". And yet somehow he still managed to escape suspicion.

All that troubled him now was the matter of Ethel, and the nagging fear in his mind that she might yet wake up and send him to the gallows. He knew Robert Swanagen and his family well enough to be welcome at their home and called there regularly, professing his concern for poor little Ethel's condition. Three days after the murders, as signs appeared that she might be improving a little, he saw his chance.

Stone called again at the Swanagens' house and offered to sit with Ethel alone for a while so the they could eat their dinner in peace. "This of course was not denied him," Bedford's Daily Mail reports, "and when he was left alone he placed his hand on the child's mouth and nostrils and smothered her. She had been so weak that nothing unusual was noted by those who returned to the room for several minutes and, when the fact was discovered, the feeling was that the poor child had died of her wounds.

"After weeping at the bedside a few minutes, the murderer left the house unaccused and unsuspected. With five of his victims in the little churchyard a mile distant and the other growing icy with death, he felt that his crime had been thoroughly covered up." (5)

As he headed home from the Swanagens' place that September evening, Stone had every reason to think he'd got away with murder once again. It was not until his father visited him in prison the following February and Bud told him the full story that anyone suspected the truth.

Stone's luck ran out when his wife Cecilia told a friend about his trip to Glendale on the night of the murder and the blood she'd seen on his shirt next morning, saying she felt sure he must know more about the killings than he let on. The friend passed this information to the authorities, who pulled Stone in for questioning. He confessed immediately to taking part in a plan to rob the Wrattens but said he was only one member of the gang responsible.

Stone's luck ran out when his wife Cecilia told a friend about his trip to Glendale on the night of the murder and the blood she'd seen on his shirt next morning, saying she felt sure he must know more about the killings than he let on. The friend passed this information to the authorities, who pulled Stone in for questioning. He confessed immediately to taking part in a plan to rob the Wrattens but said he was only one member of the gang responsible.

His version of events was that he'd arrived a little late at the Wrattens' cabin on the night they'd decided to rob it, and discovered the rest of the gang had already murdered everyone inside. "Damn you, Stone, you got here too late to see the fun," he claimed another gang member had told him. "We had a picnic with all except the old woman, and she fought like hell."

Pressed to identify the members of this supposed gang, Stone named six local men: Alonzo Williams, Grandison Cosby, William Kays, Martin Yarbrough, Gip Clark and John White, all of whom were promptly arrested. A lynch mob from Washington rode the 16 miles to Glendale hoping to hang these men without trial, but were frustrated when they discovered police had already spirited them away to Jeffersonville Prison to ensure their safety. Stone later withdrew his attempt to implicate anyone else in the killings, giving police a new confession stating he'd carried out the murders alone. (6)

Tried for murder in October 1893, Stone entered a plea of guilty, but begged the court to be lenient with him. Judge William Gardiner replied that he he must hang, and set the execution date at February 16 the following year. It would take place at Jefferson Prison in Michigan City, Indiana's state pen. (7)

Reporters turned out in force to witness Stone's death, with one onlooker remarking that about one in three of the waiting spectators seemed to be newspapermen. Also in the crowd were Sheriff Leming, Warden James Patten, who ran the prison, a group of Patten's guards and ten people chosen by Stone himself.

The first stories filed all focused on how unperturbed he seemed to be by his impending death. "Stone's last night of earth was passed in deep slumber," the Indianapolis Journal confided. "His appetite never failed him". Others described the gallows in almost fetishistic detail, noting that the height of the drop was six feet and the rope's thickness three-quarters of an inch. Once again. it's the Indianapolis Journal which gives us the fullest account:

"Almost before the spectators had settled themselves in position, Stone appeared on the trap. [.] Two guards quickly adjusted the straps round his legs and bound his arms tight to his body. Stone continued to gaze upward. The muscles of his face twitched convulsively, but he gave no other sign of emotion except that his body weaved to and fro slightly. The black cap was pulled over his face. Warden Patten then placed the loop of the noose over his head and adjusted it low on his neck. The trap was sprung at once and before the spectators were looking for it."

[.]

"The body vibrated for a second and the shoulders were slightly convulsed, then the form was motionless. The head inclined toward the left shoulder, the knot having been adjusted under the right ear on account of the enormous wen below the left jaw. Physicians quickly approached the form to count the pulse beats." (8)

Stone was pronounced dead of a broken neck at 12:21am, some 13 minutes after the trap had been pulled, his body then being cut down and placed in the waiting coffin. In an especially gruesome touch, guards found the rope's pressure had burst the large swelling on Stone's neck, blood from which now soaked the black cap Patten had pulled over his face on the gallows. (9)

All that remained was finding somewhere to bury him - but even that turned out to be no simple matter. The Wrattens' friends and neighbours objected strongly to seeing him buried in Daviess County, saying they'd dig the body up and burn it if that happened. So strong was the feeling against Stone that the Washington undertaker who'd normally have handled the burial cried off, passing the job to a colleague in distant Jeffersonville instead.

In the end, it was decided that the remains must go to the Washington farm owned by Bud's father Elias. When locals shouted about making good on their threats to dig him up, Elias laconically reminded them that the spot he'd chosen was within easy rifle range from his front porch. That seemed to do the trick: the burial went ahead without incident and the site was left undisturbed. (10)

We've already discussed the ballad inspired by this case on PlanetSlade. To read about the song and its use in Shirley Jackson's 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House, scroll down to the extracts from PlanetSlade's 2013, 2018 and 2020 letters pages below. (11)

1. A cooper's adz is hatchet-like instrument with a short handle and its blade turned through 90%. They look like this.

2. Stone continued to claim he'd never taken any money from the cabin, though not everyone believed him. Police handling the crime scene found a total of $625 still hidden there, some of it sewn into Elizabeth's dress and some secreted in a drawer. Perhaps that was all her pension savings amounted to.

3. Indianapolis Star, July 7, 1929.

4. Carter's bloodhounds also played a part in the search for Pearl Bryan's killer, which I've written about here.

5. Daily Mail (Bedford, Indiana) February 5 1894. Another newspaper, The Richmond Item, mocked Stone's string of contradictory confessions, pointing out that he'd made four altogether, each one cancelling out the last. "He now stands by confession number two and nullifies numbers one and three," it helpfully explained.

6. All these other men were later released and accepted to be innocent. This raises the interesting question or who, if anyone, Stone's wife heard him talking to in their yard on the night of the murders. None of the reports I've seen can shed any light on this.

7. Stone's was the first judicial hanging carried out inside the walls of any Indiana prison. A recent change in the law had banned them being conducted in the prison yard.

8. Indianapolis Journal, February 16, 1894.

9. Stone's body was taken from the gallows to an autopsy table in Washington, where doctors removed his brain to study it. They found it weighed 27 ounces and was in a healthy condition. "The physicians concluded that Stone was of average intelligence," reports the Huntington Weekly Herald.

10. Stone was buried next to one of his children, a young girl who'd died while her father was awaiting execution.

11. Where you see discrepancies in the various accounts I offer here, it's the new 2020 piece that's likely to be more reliable. I had far more limited sources to work from when I originally replied to Carlyn Maw's letter.

July 9, 2013. Carlyn Maw of Pasadena, California, writes:

"I was wondering if you had ever heard of The Ballad of The Rhetton Family. I can't remember where it came from but I think my grandmother taught it to our mom who taught it to us. This is what I think I remember the lyrics being:

July 9, 2013. Carlyn Maw of Pasadena, California, writes:

"I was wondering if you had ever heard of The Ballad of The Rhetton Family. I can't remember where it came from but I think my grandmother taught it to our mom who taught it to us. This is what I think I remember the lyrics being:

'First came Mama Rhetton,

She come to let me in,

He stabbed her with a corn knife,

And so his crimes begin,

'Next came Grandpa Rhetton,

Sittin' by the fire,

He snuck right up behind him,

And choked him with a wire.'

'Last came Baby Rhetton,

Sleepin' in his crib,

(something about kicking in the short ribs...?)

And he spit tobacco juice,

All over his golden head!'

"I know nothing else about it, if you do I'd love to know!"

Paul Slade replies: Thanks very much for your letter, Carlyn. It sounds like an interesting ballad, though it's one I'd never come across before. I can't claim to have done any proper research on this tale, but after an hour or so on Google, I think I've got the basic facts together.

Family names are often the least reliable way of searching for ballads like these, because they change all the time from one singer to the next - often for no better reason than a listener mishearing what's been sung, or the new singer wanting to avoid a name they find awkward to pronounce. You often get better results by choosing an unusual phrase from the ballad's lyrics and using that as your search term instead. With this in mind, I used the phrase "stabbed her with a corn knife".

That phrase, when I tapped it into Google, produced just two results, both of which led me to Shirley Jackson's 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House. The story has a character called Luke who Jackson quotes singing this song:

"The first was young Miss Grattan,

She tried not to let him in,

He stabbed her with a corn knife,

That's how his crimes begin,

"The next was Grandma Grattan,

So old and tired and grey,

She f'it off her attacker,

Until her strength gave way,

"The next was Grandpa Grattan,

A-settin' by the fire,

He crept up close behind him,

And strangled him with a wire,

"The last was Baby Grattan,

All in his trundle bed,

He stove him in the short ribs,

Until that child was dead,

"And spit tobacco juice,

All on his golden head."

That's clearly the same ballad you have in mind, though Jackson gives the murdered family's name as "Grattan" rather than "Rhetton". That's pretty close, however, and just the sort of homonym that might arise from the process I mentioned above. A "corn knife", by the way - as I've also discovered this morning - is a short machete-like blade normally used for chopping rather than stabbing.

Luke calls his song The Grattan Murders. I've looked at enough of these ballads over the past few years to develop a fairly reliable "sniff test" for those which are based on a real case, and this one definitely qualified.

I tried various combinations of "corn knife", "murder", "Gratton", "family" etc, and eventually came up with a site called http://wrattenmurders.bravepages.com. Armed with the victims' real name of "Wratten" - closer to your version than Jackson's by the way - I was able to find several other sources.

The Wratten murders happened in 1893, and were reported on page one of that year's September 20 Rocky Mountain News like this:

"Horrible Butchery. An Entire Family of Six Murdered in Cold Blood.

WASHINGTON, Ind., Sept. 19 - Last night in Harrison township, nine miles from this city, an entire family of six persons were butchered with hatchets. The family consisted of Denson Wratten, his mother, wife and three children. The eldest of the children, a girl of 12, is still living, although unconscious, and with her head cruelly gashed.

"Denson Wratten was a farmer, 35 years old, a good citizen in moderate circumstances. His good mother lived with the family and drew a pension. She did not bank her money and was supposed to keep several hundred dollars about her. This money was doubtless the motive for the murders.

"The house is a log one, a storey and a half high, and has a long kitchen annex. The murderers entered by a window, breaking the sash, and there was evidence of a fierce struggle. Wratten was sick with typhoid fever and incapable of resistance. The old lady was found upon the floor, cut terribly about the head and both hands cut off at the wrists. All were found dead upon the floor except the baby, 3 years old, which was killed in bed."

When police searched the crime scene, they found a twenty-inch corn knife, which they immediately identified as the murder weapon. The RMN would have been working from the earliest, least reliable information from the scene in rushing out the story above, and I should think that's why it mistakenly mentions hatchets instead of the knife. Elizabeth Wratten, Denson's mother, was the owner of the cabin and a Civil War widow (which is where her pension came from). Other accounts say not that her hands were severed, but that they were "slashed to the bone" as she tried to defend herself.

The rest of the song takes a bit of artistic licence with the cast, and misses a trick with Baby Henry's death. According to one account, his head was actually severed in the cradle and rolled away from his body when police tried to turn him over. Ethel, the 12-year-old who'd survived the initial attack, died of her injuries soon afterwards.

The man convicted of the murders was Bud Stone, Denson's cousin, who it was discovered had turned up at the cabin's door on the evening of September 18 asking Denson for a toothache remedy. Most accounts agree Denson actually let him in by the front door, which suggests the signs of breaking in through a window which the RMN reports were simply Stone's attempts to cover his tracks. He later named seven accomplices in the murder, some of whom seem to have burst into the cabin with him. After killing the family, they searched for Elizabeth's supposed stash of money, but found nothing.

Stone first claimed that one of the other gang members had done the killing, but later admitted he was guilty. He was hanged for the murders on February 16, 1894, at Jefferson, Indiana. A large and appreciative crowd gathered round the gallows to watch him die, and the Cincinnati Enquirer celebrated this event with a string of cheerful headlines like: "Jerked In A Joyous Jiffy to Kingdom Come" and; "The Dangle Act".

The August 11, 1960, issue of Kentucky's Park City Daily News tells us that first CE headline launched a long-running urban legend which has been delighting frat boys ever since. This insists that the Cincinnati Enquirer once reported a hanging with the headline "Jerked to Jesus" - but is, as we can see, quite untrue.

A more interesting footnote is provided by the fact that Stone's wife questioned him about bloodstains on his shirt when he first returned home after the murders, but he dismissed these stains as blood from his own troubled tooth. This is very close to what happens in a key verse from Knoxville Girl:

"Saying 'Son, what have you done,

To bloody your clothes so?'

I told my anxious mother,

I was bleeding at my nose."

There's nothing to be made of that link beyond it being an interesting little coincidence - though the PCDN does say that Stone's shirt "was finally the means of his arrest". This happened when his wife, Cecelia, told the police about his bloody clothes. She later testified against Stone in court, and it was her willingness to do this which finally made him break down and confess. The seven accomplices he named were released after Stone was hanged.

Ballads like this are always a mixture of fact and fiction, but it's clear the verse about Grandma fighting back has solid evidence to back it up. When Stone broke down and confessed, he told police the old woman had "fought like a tiger". I've found no reports which confirm the tobacco spit verse so far, which means the jury's still out on that one. My guess is that it's probably the ballad writer's invention, inserted here to underline the killer's contempt for his victims and kick listeners' outrage up another notch. Of course, I could be wrong.

I haven't been able to find any performance of the ballad on disc either, but that may be because there's still a fourth family name out there attached to it which I've yet to discover. It's got all the gory elements that usually make a ballad irresistible to folk and bluegrass singers, so I'd be surprised if somebody hasn't recorded it at one time or another.

[Carlyn later sent me a link to this Mudcat thread from November 2004. In it, Charley Noble quotes a version of the ballad above which he calls The Rattin Family. "My mother and her Greenwich Village friends used to amuse themselves in the early 1930's be singing a version of it," he explains. Carlyn says: "That makes sense, since my grandmother was also in New York in the early thirties". Carlyn herself learned the song in New York, where she lived as a child.]

October 16, 2018. Veronica Ferris of Norfolk, Virginia, writes:

"I'm intrigued by the song The Gratten Murders. In season one, episode ten of the new Netflix series The Haunting of Hill House, one of the ghosts of the house's original owners quotes it to her victim, but is cut off mid-stanza.

"I'm obsessed with movies, songs and stories that deal with real life trauma so, hearing this song on the show, I wanted to know how it ends. If you could send me a link or a message containing the full poem/song I would greatly appreciate it."

Paul Slade replies: Thanks for your note. As it happens, I've already tackled this song, which another PlanetSlade reader asked me about back in 2013. It opens with this verse: "The first was young Miss Grattan /She tried not to let him in / He stabbed her with a corn knife / That's how his crimes begin." Grandma Grattan's the next to go, then Grandpa, then the baby and so on.

The Netflix series imported this song directly from Shirley Jackson's source novel, published in 1959, which also gives the family name as Grattan. According to her biographer Ruth Franklin, Jackson used to sing it to her children as a lullaby when they were small. The ballad's based on the real-life murders of the six-strong Wratten family in 1893 Indiana. To read the full story of those killings, just scroll down to PlanetSlade's August letters section here.

Under one name or another, The Grattan Murders looks to be at least 100 years old, and has just the kind of blood-thirsty lyrics which normally make a murder ballad popular. So far, though, I've been unable to find any band or artist who's recorded it. Perhaps someone out there in PlanetSlade's readership will put that right.

February 6, 2020. Matt Aukamp of Pennsylvania writes:

"Hello! I run a podcast called Every Folk Song where I dissect the history, evolution and meaning of various folk songs: one per episode, in order of Roud Number. Lately, I have been brushing up against your research a lot, so I wanted to reach out and see if you'd be willing to talk to me on the show! The things that Id love to interview you about are:

"First, the Wratten Family Murders. I've been working hard on research into the ballad, and I believe you may be the first to have drawn a connection between the ballad and the actual murders. I'd love to talk to you briefly about that.

"Second, it seems that you've done a dive into Pretty Polly (the next song on my list) - so deep that there's barely anything left to research! After reading your article on the ballad, I realized that I had two options: 1) produce a nearly identical piece of research, turning up the same details and almost definitely citing you heavily throughout. Or 2) invite you on the show to walk through the details yourself! I thought of all the people to tell that story on a podcast, it'd be you. Please let me know if you'd be interested in this."

[Matt and I duly did the interview he mentions, the results of which you can find in his Wratten Family episode here. He was kind enough to send me a couple of recordings he'd arranged of the song - the first ever made as far as I know. One of these is by a Philadelphia band called The Windfarmers and the other by Adam Gordon, a fan of Matt's podcast. You can hear them both on the episode's webpage. In the course of our conversation, Matt also mentioned that he was just about to go on a field trip to the Daviess County Historical Society in Indiana to examine their material on the murders. When he got back, he dropped me a line again to let me know how he'd got on.]

February 24, 2020. Matt Aukamp writes:

February 24, 2020. Matt Aukamp writes:

"I just got back from my trip to Indiana and your book was waiting for me! Thanks so much for sending that along; I can't wait to read it. As for the trip, I learned a ton of stuff but the two things I thought would be the most interesting to you personally are as follows:

"1) The corn knife! Grisly as it is, I got to hold the actual 20-inch corn knife that was used by Bud Stone. It was held by their county coroner until he passed away and then hung in the offices of the jail for several decades until they tore it down and gave it to the Daviess County Historical Society. Gave me chills to see it - and then they were like 'You wanna hold it?' Super eerie.

"2) This news clipping from the Vincennes Valley Advance newspaper. On August 3rd, 1967, they posted an article about the Wratten Family murders. In the following week's letters column, they posted a small reference to a folk song about the Wratten Murders: 'Judge Curtis G. Shake recalled the mass murder produced a folk song about how cruel Bud Stone was in wiping out a Daviess county family'.

"As your research had been the only thing I'd ever seen connecting the song to the murders (as likely as the connection seemed) I think this reference from 50 years ago all but proves your theory! I thought you'd like to know."

Paul Slade replies: Wow! Takes me back to my 2010 visit to Kentucky and examining the Pearl Bryan relics they had in a small museum there. It's impossible to say this without sounding disturbingly ghoulish, but getting up close and personal like this with the artefacts of a case you've been immersed in researching is always an unforgettable experience. Can't wait to hear your Wratten Family podcast episode!

December: Shirley Jackson’s lullaby

September brought a letter to PlanetSlade from Sarah Hyman DeWitt, the younger daughter of celebrated horror writer Shirley Jackson.

Jackson’s 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House became a hit Netflix series in 2018, complete with a scene using The Grattan Murders, a gory old murder ballad which we’ve discussed before. Jackson would sometimes sing this ballad as a lullaby when putting her four young children to bed, and it’s clearly an experience Sarah has never forgotten.

“I know my mother’s version of The Grattan Murders well,” she writes. “She sang it in a rather odd, Cockney-like accent: “'E crep' up close be'ind 'im”, “Until her stee-rength gave way” and “'E stove 'im in the short-ribs, until that chee-ild was dead.”

I expect she learned it from her father, Leslie Jackson, who was an English immigrant to America, with a large collection of English music hall songs. I find it odd that the song seems to have made it to England, and yet is so rare in America. I have never heard anyone except members of my family sing any version of it. My sister and I sang it on a BBC ‘alphabet of horror’ series, and I would be happy to sing it for you.

“As Sadie Damascus, I am a nonprofessional singer of Child ballads and other bad old songs, and am known in a number of folk music societies' online gatherings. I lectured on the Child Ballads for about five years on a local community radio station. I am so glad to discover your website.”

I was delighted to receive this letter, not only because I’ve always loved the lullaby story – which Sarah confirms is true, by the way - but also because I could now imagine Jackson’s rendition in precisely the style she sang it. Sarah and I arranged a Zoom call so she could perform the song for me in her mother’s style, which she’s kindly allowed me to post on YouTube here.

It’s interesting to discover that Jackson may have first come across the song through her husband’s interest in English music hall. When ballad sheets fell away around 1850, the same style of street songs they’d offered sometimes found a new home on the music hall stage. Mrs Dyer, the Old Baby Farmer is a good example of this, and The Grattan Murders may well be another.

The fact that the song isn’t better known is baffling. It’s just the sort of gory True Crime ballad that folk and bluegrass singers normally find irresistible, and yet almost no-one seems to have recorded it. You’d have thought the Netflix Hill House adaption alone would have prompted a cover or two, but if so I’ve been unable to find them. Maybe someone reading this will be prompted to give it a try?