The grave and gay no longer now,

The grave and gay no longer now,

Are separately singled,

The gay and grave, the grave and gay,

Are curiously co-mingled,

O, Shade of Whitfield! Can it with,

Thy saintly doctrines tally,

That in thy graveyard there should be,

High jinks and wild Aunt Sally?

Ill fare the fair who haunt that fair,

In search of comicality,

'Tis most unfair to hold a fair,

In any such locality.

- Anonymous newspaper poem, September 1887.

It started with an anonymous letter to the St Pancras coroner in North London. Wasn't there something a little odd, the writer asked, about just how hastily Elizabeth Thomas had been buried?

Elizabeth was only 27 years old when she died on October 28, 1808, and was buried next day at St Mary's parish church in Islington. By November 1 - just three days after her death - a headstone was already erected on the grave, Elizabeth's date of death carved firmly into its surface. "She had no fault, save what travellers give the moon," the stone read. "Her light was lovely, but she died too soon."

No arguments there - but now the question was precisely how she'd died. The letter raised "very strong suspicions" that it was not natural causes, said the Kentish Gazette. "The lady died on Friday, was buried on Saturday and the gentleman with whom she lived (they not being married) left town on Sunday and embarked at Portsmouth on Monday for Spain," it added. Not only that, but instead of waiting the usual six months to allow the earth of a new grave to settle before adding a headstone, this unnamed gentleman had insisted Elizabeth's stone be up within three days. Why had he been in such a rush? (1)

This was starting to look like foul play, so Islington's parish officials were asked to open Elizabeth's grave and bring her body into the church for examination by a coroner's jury. This was done on the Thursday morning after her death (November 3). On examining the body, the coroner found a silver pin, about eight inches long, which had been pushed in through Elizabeth's left side and deep into her heart. Now her death looked more suspicious than ever.

The doctor who'd attended Elizabeth in her last hours was called to give evidence. He testified that, despite his best efforts to save her, Elizabeth had died of natural causes after a long illness. He'd pushed the pin in himself, he added, but done so only when she was already dead and in her coffin. Elizabeth, he claimed, had suffered from a morbid fear of being buried alive and the pin was a means of ensuring that could not happen.

Fear of premature burial was quite common at this time. The first safety coffins - equipped with various devices allowing their occupants to raise the alarm - appeared in the 1790s and were widely used till the end of London's second cholera epidemic in 1866. "It was at her own request that the pin was inserted," Islington's 1808 Parish Register says of Elizabeth. But the newspapers disagreed. "The pin was inserted at the request of the gentleman," reported the Kentish Gazette a week after the coroner's examination. Which account is right, we don't know.

Asked why Elizabeth's partner had been in such a hurry to dispose of her remains and leave the country, the doctor replied that he'd been "under the necessity of embarking immediately for the Continent [and] was desirous of seeing her previously interred and paying the last honour to her remains". That's from the Islington Parish Register again and it's the only explanation we ever get for her partner's behaviour. There's no indication either in the register or the press reports that he himself was ever questioned - presumably because he was now somewhere in Spain and well beyond the reach of a British jury.

Islington's Parish Register seems quite satisfied with the doctor's evidence. The facts of Elizabeth's death were "proved by corroborative testimony" it says, with "nothing whatever appearing to incriminate any of the parties concerned". When the jury returned, its verdict was "death by the visitation of God". This was quite a common verdict at the time and seems to have been used whenever there was natural death but the current state of medical knowledge allowed for nothing more precise. (2, 3)

"Nowadays in such circumstances, the coroner would order a post-mortem examination," Coroners' Society archivist Nicholas Rheinberg told me. "But in 1808 autopsies were rare." To illustrate the way "visitation of God" was then used, Rheinberg cited an 1822 jury verdict regarding a dead man who'd long suffered from asthma. "AB departed this life by visitation of God in a natural way," the jury ruled. "To wit, of the disease and distemper aforesaid and not by any hurt or injury received from any person to the knowledge of the said jurors." It's fair to conclude, then, that Elizabeth's jury believed she'd died a natural death from unknown causes. (4)

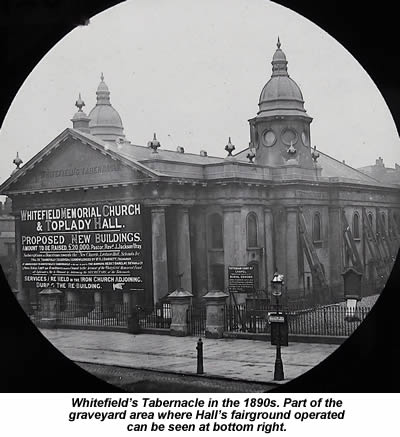

As soon as this verdict was in, her family obtained permission to rebury Elizabeth at Whitefield's Tabernacle, a Methodist chapel in Tottenham Court Road. This was duly done on November 8, though the church's burial book shows her with a different surname. There, she is listed as Elizabeth Edwards, not Elizabeth Thomas. All the book's other details confirm it's the same woman, however: 27 years old, buried on November 8 and born in the parish of St Mary's, Islington.

How the Edwards/Thomas discrepancy arose, I don't know. My guess is that "Edwards" was her birth surname and "Thomas" that of her mysterious partner in Islington. She's described as "Mrs Elizabeth Emma Thomas" on that headstone so, married or not, he evidently thought of her as his wife. If I'm right about this, then her family's restoration of "Edwards" in the burial book begins to look like them reclaiming her from a man they didn't much like - or perhaps even suspected of killing her.

Whatever the truth of her demise, Elizabeth's tale ends with her resting peacefully in a churchyard just north of what's now Goodge Street station in central London. As we'll see in a moment, though, no-one buried on that site has ever been left undisturbed for long.

George Whitefield, born in 1714, was a Methodist preacher. Working alongside the denomination's founder John Wesley in its earliest years, he became famous for his fiery outdoor sermons and evangelical zeal. In 1738, he made the first of seven visits to America, where he became friends with Benjamin Franklin and played a leading role in the Evangelical Revival there.

George Whitefield, born in 1714, was a Methodist preacher. Working alongside the denomination's founder John Wesley in its earliest years, he became famous for his fiery outdoor sermons and evangelical zeal. In 1738, he made the first of seven visits to America, where he became friends with Benjamin Franklin and played a leading role in the Evangelical Revival there.

Christianity Today magazine calls Whitefield "probably the most famous religious figure of the eighteenth century", saying he preached at least 18,000 times to a total of some ten million listeners. He could make himself heard to a crowd of 25,000 or even 30,000 people, a figure carefully calculated by Franklin when he attended a Whitefield sermon in Philadelphia. "He had a loud and clear voice and articulated his words and sentences so perfectly that he might be heard and understood at a great distance," Franklin reported, "especially as his auditors however numerous, observ'd the most exact silence." (6, 7)

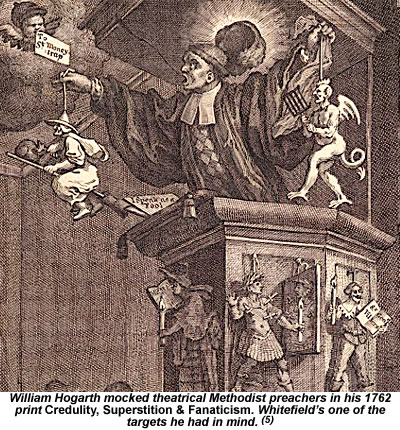

You can see why they were so keen not to miss anything. "He portrayed the lives of biblical characters with a realism no one had seen before," Christianity Today continues. "He cried, he danced, he screamed. Among the enthralled was David Garrick, then the most famous actor in Britain. 'I would give a hundred guineas,' he said, 'if I could say 'Oh' like Mr. Whitefield'." (8)

Methodism was still accepted as a branch of the Church of England at this time - the split wouldn't come till 1795 - but Whitefield's theatrical style was much resented in the parent church. In 1741, when his followers built him a wooden chapel in London's City Road, he was careful to call it a "Tabernacle" to stress its strictly temporary nature. The original Tabernacle, of course, was the portable altar Moses' followers carried with them through the desert. By adopting its name, Whitefield hoped to reassure the nation's official church that he and his worshippers were no threat.

This uneasy truce lasted only till 1756. Whitefield was preaching twice a week at a dissenters' chapel in Long Acre by then and that's where the trouble broke out. "The resistance to his preaching there was two-pronged," Thomas Kidd writes in his 2014 biography of the great man. "Some came from the nearby theatre community, which resented Whitefield's anti-theatre preaching. Hooligans sang and made 'an odd kind of noise' outside the chapel and occasionally heaved large stones through the windows. Opposition also came from local Anglican authorities, especially Bishop Zachary Pearce, the Dean of Westminster. [.] The bishop tried to ban Whitefield from speaking at Long Acre because of its dissenting affiliation." (9)

Whitefield replied that the bishop really should have better thing to do with his time than trying to stop him from preaching the gospel - especially at a time, he said, "when France, Rome and hell ought to be the common butt of our resentment". When the harassment continued, he described it as "premeditated rioting" and claimed someone had hired "the baser sort" of Londoners to carry it out. "Things took a dark turn in April 1756 when he began receiving death threats," Kidd continues. "Three letters promised 'a certain, sudden and unavoidable stroke' if he did not stop preaching or if he pursued legal proceedings against his tormenters."

Clearly this couldn't go on. Helped by some money from his patron the Countess of Huntingdon, Whitefield leased a site called the Crab and Walnut Tree Field in Tottenham Court Road and drew up plans for a new Tabernacle there. The neighbourhood was then on the very edge of London, where the city's buildings gave way to open fields. Contemporary woodcuts show that what's now Tottenham Court Road was, in 1756, little more than a rural cart track. (10)

Before building work could begin, Whitefield had to drain a large pond on the site known as the Little Sea, subsidence from which would haunt the building for many years to come. Construction was completed in 1760, giving him a brand new chapel which contemporary reports say could fit as many as 5,000 people. His enemies scornfully nick-named the building "Whitefield's Soul Trap". Kinder souls dubbed it "The Dissenters' Cathedral".

The new Tabernacle was flanked by a patch of burial ground on either side. When Whitefield's wife Elizabeth died in 1768, he buried her there. Another early resident was Bartholomew Goodson, who was attending a March 1772 service at the Tabernacle when a bolt of lightning struck him dead. The Reverend Augustus Toplady, who composed Rock of Ages, is buried there too, his own remains being interred under the Tabernacle's floor in 1778. (11)

Whitefield himself died during his 1770 trip to Massachusetts, but his body was never brought home. His successor in running the Tabernacle was Reverend Torial Joss, who took up Whitefield's old campaign to have its burial ground consecrated by the Anglican church. Fed up with the Bishop of London's refusal to permit this, he decided in 1780 that drastic action was called for. St Christopher-le-Stocks, a church next to the Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, was being demolished to make room for a bank extension, so why not simply steal some consecrated soil from that graveyard and scatter it over the Tabernacle's ground instead? (12)

And that's exactly what he did. Writing in his 1855 book Curiosities of London, John Timbs says the Tabernacle burial ground's topsoil was "brought from the churchyard of St Christopher-le-Stocks in 1780, by which consecration fees were saved". According to a Pall Mall Gazette report 30 years later, "several cartloads" of sacred earth were dug up, transported the 2½ miles to Tottenham Court Road - most likely by dead of night - and strewn across the Tabernacle's ground. (13, 14)

Even this ingenious back-door consecration couldn't protect the Tabernacle's burial ground from the bodysnatchers then plaguing London. Medical science was advancing fast but, until the Anatomy Act was passed in 1832, trainee surgeons had no legal source of corpses to study except those of executed criminals. There were nowhere near enough of these to meet demand, so a lively trade sprung up between men who were willing to illegally excavate new-buried bodies and the medical schools who bought all the corpses they could supply, no questions asked.

London County Council's 1949 architectural survey of Tottenham Court Road notes that the Tabernacle had "considerable trouble" with body-snatchers in the 1700s. In March 1776, The Gentleman's Magazine reported that the remains of more than 20 dead bodies had been discovered in a shed in Tottenham Court Road, adding that they were "supposed to have been deposited there by traders to the surgeons". Joshua Naples, the infamous bodysnatcher behind The Diary of Resurrectionist, records meeting the rest of his gang "at Tottenham Court Road" one night in December 1812 - though, on that occasion at least, they don't seem to have dug anyone up there. Naples went home to Southwark and got drunk instead. (15, 16, 17)

Whitefield's original lease on the Tabernacle ran out in 1827, forcing the chapel to suspend its services and close the churchyard to new burials. The whole site was put up for public auction on September 21 that year. "The property included the chapel, vestry rooms, almshouses and two small lodges beside the extensive burial ground, which was stated to be eligible building land," the LCC survey tells us. That last point's an important one. Whatever dirt may have been scattered over its surface in 1780, Whitefield's graveyard was still unconsecrated in the eyes of the law. That meant it presented none of the legal hurdles blocking development which automatically applied to consecrated ground, and the auctioneers knew this would help it fetch a better price. No wonder they were so keen to underline the fact.

In the event, this proved academic as the property was eventually withdrawn from auction and its freehold bought by the chapel trustees. That purchase came in 1831, thanks to a mortgage loan the trustees were able to secure from a Mr Tudor. New burials - the fees from which were a big part of the chapel's income - resumed in the same year.

In 1852, Parliament passed the first of a string of Burial Acts, tightening up on the regulation of graveyards throughout the country. This led to the Tabernacle's over-stuffed burial ground being closed again in 1853, creating another financial crisis for the trustees. Four years later, the chapel was forced to rebuild after a disastrous fire, hitting its finances yet again and ultimately leading Tudor to foreclose on the trustees' mortgage.

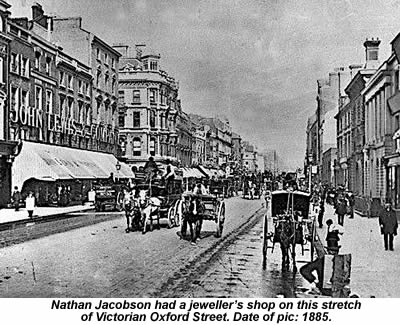

Shortly after the fire, the courts ordered the whole site to be split into separate lots and returned to auction - once again with the assurance that the burial ground could be built on. The trustees took a mortgage with the London Congregational Building Society, which let them buy the chapel itself, together with the footprint of ground it sat on and the southern patch of burial ground. But the northern patch of the burial ground's freehold fell into other hands. The lion's share of it went to an Oxford Street watchmaker and jeweller called Nathan Woolf Jacobson, whose development plans would pitch the site into its most turbulent years yet.

Nathan Jacobson first appears in the historical record with the UK census of 1851, where he's listed as a 24-year-old watchmaker with a wife and two daughters sharing his Oxford Street home. His wife at that point was Rosa (25) and their children were Abigail, just two years old and Alice, her baby sister. They had one live-in servant, a girl called Ellen Lloyd. (18)

Nathan Jacobson first appears in the historical record with the UK census of 1851, where he's listed as a 24-year-old watchmaker with a wife and two daughters sharing his Oxford Street home. His wife at that point was Rosa (25) and their children were Abigail, just two years old and Alice, her baby sister. They had one live-in servant, a girl called Ellen Lloyd. (18)

A year later, on July 5, 1852, Jacobson found himself on trial at the Old Bailey for breaking and entering. The charge was that he and a publican friend, Thomas Lawrence, had broken into a house near Regent's Park and stolen a vase they found there. They were eventually convicted of the lesser charge of receiving stolen property, but not before the court heard some evidence revealing just what a slippery customer Jacobson could be.

Testifying for the prosecution, Constable Frederick Shaw said he'd been watching Lawrence's pub, the Royal Oak in Chenies Street, at about 10:30am on June 5, when he saw Jacobson go inside. "I knew him before," Shaw told the court, suggesting the police had already identified Jacobson as someone worth keeping an eye on. (19)

Jacobson stayed in the pub for about five minutes, then came out with Lawrence and followed him to Lawrence's stable in the nearby North Street Mews, where they remained inside for a quarter of an hour. "Neither of the prisoners had anything with them when they went into the stable," Shaw testified. "Then they came out and Jacobson was carrying a bundle under his arm, tied up in this handkerchief which I now produce. It contained this vase and stand."

The two men separated, and Shaw followed Jacobson. "I stopped him in Mortimer Street, which is in line with Goodge Street," he said. "I told him I was a police officer and asked him what he had got. He said 'A vase'. I asked him where he had got it from. He said he had bought it. I asked him when. He said 'This morning'. I asked him the name of the person of whom he bought it. He made no reply. [.] I then asked him his name and he said his name was Woolf. At this time, I was joined by Officer Smith. The prisoner then said that his name was Jacobson and that my brother officer knew him."

When Shaw asked him his address, Jacobson told him he kept a shop at 16 Tottenham Court Road, but denied having any other place of business. That was not true, Shaw testified, as he also had the shop at 311-315 Oxford Street - an address Jacobson clearly preferred not to link himself to that night.

Leopold Redpath, the owner of the Regent's Park house, confirmed in court that the vase Jacobson was found with was the one he'd had stolen and valued it at about £20 (equivalent to about £2,700 today). Both Jacobson and Lawrence were sentenced to ten years transportation for receiving stolen property, but seem to have got no further than Portsmouth Prison. Jacobson served four years there before being freed on licence in July 1856. Three years later, he had his first son, Maurice Woolf Jacobson, who we'll meet again later in our tale.

In 1863, Jacobson made his first attempt to develop the burial ground land he'd just bought in Tottenham Court Road. "Coffins were seen to be cut through and graves desecrated," the London Encyclopedia tells us. There were "many unseemly conflicts between the excavation contractors and the inhabitants of the neighbourhood," adds the LCC survey. Jacobson was convicted and fined for disturbing human remains on the site without the Government licence he should first have obtained. Shortly after this, a senior judge granted an injunction banning building work on the site. (20)

This was enough to halt Jacobson's plans and persuade him to leave the site untouched for almost 20 years. Abandoned by its owner, it was soon broken into by local kids, who sometimes left the bones they'd been playing with thrown aside on Tottenham Court Road's pavement as they left. Pedestrians passing by next morning must surely have shuddered as they hurried on to work.

In May 1865, Jacobson was back at the Old Bailey again, this time as the victim of a burglary at his Oxford Street shop. William Vesey and Charles Davis were charged with stealing £800 worth of watches, rings and assorted jewellery there, but both found not guilty. With stock like that on hand - the value of the stolen goods would be close to £100,000 today - his business was clearly doing well, and that's a conclusion supported by the 1871 census. (21, 22)

Jacobson and his family were still at the Oxford Street address, but now with two servants instead of one. Rosa, who died in 1863, has been replaced by a new, much younger wife called Rebecca who, at 18 years old, was about 25 years Jacobson's junior. The six children listed are Alice (18), Billah (17), Ena (16), Esther (13), Joseph (4) and Nathan Jr (under 1). Neither Abigail, who'd then have been 22, nor Maurice, who'd have been 12, are mentioned on the 1871 census form, but all that tells us is that neither spent that particular night in the Oxford Street house. Both may have been working by then - Maurice as an apprentice - and living with their employers. (23)

The burial ground held over 30,000 bodies at this time and Jacobson's abandoned excavations had left their graves in a truly horrific state. Benjamin Disraeli's government ordered the Vestry of St Pancras to tear down Jacobson's fencing and plant the half-acre site with fresh turf and trees. Jacobson responded with a lawsuit, pointing out that much of the ground the vestry had commandeered was his freehold and demanding that it be returned to him. Sir George Jessel, then Britain's Master of the Rolls, agreed, granting an injunction which ensured the vestry's workmen were ejected with their landscaping barely begun. Heartened by this result, Jacobson decided it was time to try his luck with some fresh building work on the site.

Digging began anew in March 1880. As soon as the authorities at St Pancras Parish got wind of this, they dispatched William Rouch, one of their inspectors, to see how carefully the work was being carried out. Jacobson's men refused to let him on to the site at first, but Rouch came back with a magistrate's order which left them no choice. He found they'd already dug a large hole there, 12 feet wide, 20 feet long and up to six feet deep. Shoulder bones, skulls, rib bones, leg bones and spinal bones - all of them human - were being ripped out of this hole by pickaxe and shovel, then thrown into a long trench and covered with an inch of mouldy earth. Rouch could see scraps of wood from broken and rotting coffins in the trench too. Jacobson's men claimed that all the trench's bones would eventually be placed in a vault which they planned to build on the site. Just when this might happen, they couldn't say.

Carts trundled on and off the burial ground all day, each lingering just long enough to be loaded up with shovelfuls of the newly-excavated earth and all the small bone fragments still mixed among it. A man stood in each cart as it was loaded, picking out any identifiable bones that had been missed by his colleagues and hurling them out again for consignment to the trench. Several hundred cartloads of the burial ground's earth were removed in this way and driven off to be sold to London's nurserymen and gardeners - some of whom later found finger bones and human teeth among the nutrient-rich soil they'd bought.

St Pancras Parish took Jacobson to court, renewing the old charge that he was removing human remains without a licence. The case began at Marlborough Street Police Court at the beginning of April 1880 and reached its final conclusion in the High Court eight months later, but I'm going to compress all its various stages into a single account here for the sake of brevity.

Rouch testified to all he'd seen on the site, reminding the court that this ground was "thickly studded with graves in every part and in a populous neighbourhood". Mr Spence, another St Pancras Parish inspector who'd also spent a day on site, added that he'd seen "18 or 20 skulls taken out of the ground" and thrown into the rapidly-filling trench. (24)

Edwin Ridley, a Tottenham Court Road shopkeeper with premises near the burial ground, testified that he'd watched one of Jacobson's men scavenging through a box of assorted bones there to see if he could find any human teeth, which he knew would fetch a good price from London dentists. "On his coming across a jawbone with some white teeth in it, he took the teeth out and put them into his pocket," Ridley said. "There were bones of every description in that box." (25)

Mr Webster, speaking for the defence, said Jacobson had consulted a St George's Hospital chemistry professor before starting the 1880 work, who'd "assured him it could be dealt without interfering with the bones and without danger to the public health". Dr Richardson, a character witness, insisted that all Jacobson's work was "done with due regard to public decency". (26)

The original charge had by now been replaced with a new one claiming Jacobson was disinterring the site's bones "in an improper and indecent manner", and that left the jury with two points of law to decide. First: had any of the bones disturbed at Tottenham Court Road formed an integral skeleton before being dug up? If so, they had the legal status of human remains and so qualified for the law's protection. And, second: assuming they did count as human remains, had Jacobson removed them in an indecent or improper way?

"The jury found that the bones were human remains," the Liverpool Mercury reported, "but were not prepared to say that they had been removed in an improper or indecent manner". That left the legality of Jacobson's actions unsettled and it was not till a final hearing in December 1880 that Mr Justice Field, a High Court judge, decided that he had committed a Common Law offence. Field fined Jacobson £25 - worth about £3,000 today - and told him he must also pay all the prosecution's costs. "In his lordship's opinion, it was a very serious offence that the remains of human beings should be disturbed and subjected to indignities," the Evening Standard told its readers. (27, 28)

The same issue of the Standard carried an angry editorial about the case. "One court sells the ground for building and another fines the purchaser for disturbing the bodies which rested in the soil," it protested. "The ground is still private property; it is shut up behind hoardings; yet it has so far a public character that the owner cannot make use of it. [.] It is obvious that burials legally conducted in a place set apart for the purpose ought to carry the legal force of consecration with them and to make the ground forever inalienable to baser uses."

That brings us neatly to 1881 - and to yet another UK census form. Jacobson was still heading the Oxford Street household, now aged 54 and describing himself as a "dealer in works of art". Rebecca has been replaced by a still younger wife called Annie, who's just 25. The five children in the house are Joseph (14), Nathan Jr (11), Charles (4), Rebecca Jr (2) and Julius (under 1). Where the family had employed a single live-in servant in 1851 and two in 1871, it now had three: a porter, a cook and a nursemaid.

Jacobson died on April 23, 1881, less than three weeks after those census details were taken. He left no will, which meant the default assumption was that all his assets, including the burial ground's freehold, would go to Annie, his young widow. A group of his children - Joseph, Nathan, Charles, Rebecca and Julius - were corralled together by a adult friend of the family called Charles Wingard and persuaded to launch a legal action over the estate. Ranged against them were the widowed Annie, plus Alice Jacobson (now Alice Stevens) and her husband. (29)

The resulting lawsuit of Jacobson v Jacobson got underway on May 7, 1881 and would not finally be resolved until 24 years later. Handling cases like this fell to the High Court's Chancery division, which stepped in to supervise Jacobson's estate until the lawsuit could be settled. Still the burial ground was stuck in limbo: its owner was barred from developing it, the vestry was barred from taking it over and the chapel couldn't afford to buy it. Now that the courts were involved, finding a solution to this impasse was going to be more difficult than ever. (30)

As with any neglected patch of land in London, the burial ground fell into a more and more disgusting state. Here's how the Pall Mall Gazette described its condition in July 1886:

As with any neglected patch of land in London, the burial ground fell into a more and more disgusting state. Here's how the Pall Mall Gazette described its condition in July 1886:

This burial place is now a 'no man's land', a hideous eyesore visible to every passer by, in one of London's main arteries. It has become a receptacle for rubbish of all kinds; old shoes, broken bottles, scrap iron, dead cats and other abominations lie scattered over its surface, with here and there a fragment of human bone. The two or three tombstones which remain are fenced in by a hoarding covered with gaudy advertisements and these poor few are almost hidden by scraps of paper, the remains of old posters.

All the rest have disappeared, carried away in fragments by the urchins who, before the present board fencing was put up, used to play football with the skulls they scooped up from the reeking mould with their sacrilegious hands. [.] It is a disgrace to this mighty city that, in one of its most frequented thoroughfares, there should be seen a sight so exquisitely painful and shocking to a sense of decency as this neglected Golgotha.

The newspapers were quick to paint the Jacobson family as the villains of the piece here, but step back for a moment and you can see why they felt they had a legitimate grievance. Assured that the site was "eligible building land", Nathan had paid a price for it which reflected that potential and the profit he hoped its development would bring. Then he found those plans thwarted and the land itself worth only a fraction of what he'd paid for it. His only likely buyer looked to be the chapel's trustees - and there had been talks there - but any offer they made valued the site only as waste ground.

The plot's new freeholder (presumably the estate) now found itself in exactly the same position. Someone there seems to have decided the answer was to pile a little extra pressure on the chapel by making the burial ground even more of a nuisance than it already was. With this in mind, the freeholder leased Jacobson's old patch of it to James Hall, a fairground operator with sites already running in Fetter Lane and other parts of London.

Hall's showmen moved on to the Tottenham Court Road site in June 1887, installing a steam-driven roundabout which played its own music, a set of swing boats, a peep show and a rifle range. Performers there included a strong woman, Monsieur Bihin ("the Belgian Giant") and a pair of acrobat sisters called Violetta and Annie. Another performer there, billed as "The Woman With the Iron Jaw", took to using the site's last remaining flat tombstone as a stage for her act. (31)

All this activity was set up just a foot or two from the chapel's exterior wall, making the noise inside unbearable whenever its minister, Reverend Jackson Wray, tried to conduct a service or hold one of the chapel's regular school classes. Harry Gaze, a trustee there, complained that the school room in particular was now unusable "owing to the intolerable noise of the rifle gallery close against the wall". The freeholder's message could not be clearer: "Pay me what I want for my land or you'll never get a minute's peace again".

More painful still was the desecration of the graveyard itself. Hall had complied with a court order requiring him to clear out the dead cats, old packing cases and assorted rubbish strewn on the section he now occupied, but other problems remained untouched. There were reports of the fairground's performing monkeys dancing on tombstones and of the rides there remaining in use till 3am. Soon the police were recording cases of violent assault there and of pickpockets harvesting wallets from unsuspecting revellers.

"No words of mine can express my grief and disgust at the base uses to which God's Acre is condemned," Wray said in a letter to the St Pancras Guardian. "We have tried to put a stop to this abominable profanation. The vestry told us that it had no power and it might have told us also that it did not very much care. We applied to the magistrate and he, too, declared that he cannot help us. We obtained counsel's opinion and have, at length, applied to Chancery for an injunction. But it is freehold property and English law has profound reverence for that fetish. What may be the result I cannot say." (32)

There was more bad news at the sanitary committee's June 29 meeting, where its medical officer, Dr Sykes, said the plot's status as private property made it impossible for the police to evict the fairground or force it to close down. One "active gentleman" supporting the chapel had recruited Sir Julian Goldsmid, the local MP, to try and help, written to the Home Secretary and even contacted Scotland Yard. They'd all been quick to sympathise, but none had provided any concrete help. (33)

The chapel's trustees managed to get a Chancery injunction banning the fairground from operating for the one hour every Wednesday evening when the chapel's service was in progress, but otherwise the nuisance continued as before. They immediately set about trying to get this injunction extended, but were told this application would have to wait its turn in the court's calendar. With luck, they'd get a hearing sometime around Christmas. Meanwhile, St Pancras Vestry suggested offering £500 for the land, half of which it was prepared to put up itself. The rest would have to come from the trustees.

Hall, the fairground operator leasing the ground, replied to his critics in a letter to the St Pancras Guardian on July 9. "The position in which they are placed is their own fault," he said. "They would like to get the land back for a mere song, [or] by threats of injunction in Chancery etc. But that is not the way to do business. If the trustees or the parish authorities are really desirous of buying the ground, I am prepared as lessee and also on behalf of the freeholder, to go into the matter with them in a proper and businesslike manner. But if they think to frighten me or the freeholder into selling for less than free value, they labour under a serious mistake."

If the freeholder's strategy wasn't clear before, it certainly was now. "The graveyard cannot be sold for building purposes, but the owners refuse to sell it except at the price of building land," explained the Echo. "It would seem almost as he were trying to force a sale by making the ground a nuisance to his neighbours," added the City Press. (34)

The struggle that filled the rest of 1887 was a long and labyrinthine one, so I'm going to switch to bullet points here and just give you the edited highlights. We'll pick up the full tale again as the battle's final resolution comes into sight.

. August 19, 1887: The police bring Hall before Marlborough Street Magistrates Court on charges of operating an illegal fair at Tottenham Court Road. The prosecution relies on provisions in the Unlawful Fairs Act, so the first question to be resolved is whether Hall's set-up is subject to that Act's terms. His defence lawyer, Mr Lynch, argues that a fair must include goods on sale as well as amusements, saying Hall's amusements-only operation is therefore exempt. Mr De Rutzen, the magistrate, agrees and dismisses the summons accordingly.

. August 29, 1887: A letter to the Daily Telegraph from Hall reveals just how big a gap remains to be bridged in negotiations for the site. "I have offered to sell them the ground at a very low figure - namely, £4,000," he writes. "It has been valued at £14,000 by eminent surveyors. But [the trustees'] bid was so very ridiculous - viz £500 - that I can only think it was made in jest. Or else they wanted the ground made a present to them, which the freeholder is not inclined to do."

. August 30, 1887: Gaze, who seems to be the most determined of the chapel's trustees, goes to war with Hall in the Telegraph's letters column. "We shall not be induced by the existing nuisance to pay a fictitious price for ground which is not available for building purposes," he writes. "Mr Hall certainly offered to sell us the ground, but as his lesseeship was confined to a weekly tenancy, we have never taken his offer seriously and do not require his advice." Hall replies, claiming that he actually has a lease of 21 years on the burial ground and pays over £500 a year in rent. "If the chapel authorities have not taken my offer seriously, it is time that they should," he says.

. September 3, 1887: "Mr Hall has had the misfortune to fall down a disused well at another of his shows in Fetter Lane," the St Pancras Times chortles. "The unsuspected covering gave way and let him down some 15 or 20 feet, whereby he has received serious injuries to his spine." Medieval people would have seen this as divine retribution for Hall's desecration of the Tabernacle's graves, the paper adds. "Let us hope he may take it as a caution."

. September 4, 1887: A visiting American tells the Echo about his recent stroll up Tottenham Court Road. "He saw a man about 40 years old, perfectly sober, trying to prevent a crowd of noisy men and women from dancing on his mother's grave," the paper reports. "The picture presented by that grief-stricken man will never fade from his memory."

. September 5, 1887: The House of Commons publishes Harry Levy-Lawson's Vacant Grounds (Nuisances Prevention) Bill. Levy-Lawson, the MP for St Pancras West, wants to amend the existing law to ban not only permanent structures on any disused burial site (as it already does), but also tents and other temporary structures like the ones Hall uses. Levy-Lawson has written the Bill purely to tackle the problem at Tottenham Court Road.

. September 9, 1887: Herman Plake, a German manufacturer of cane window blinds with premises next to the burial ground, sues Hall for allowing an 18ft tall booth there to be erected directly in front of Plake's windows. The booth, which houses the fair's roundabout, has blocked his light so badly that he can no longer conduct his business properly, Plake says. The judge finds in his favour and orders Hall to ensure the booth's removed.

. September 10, 1887: Home Secretary Henry Matthews blocks the progress of Levy-Lawson's bill, effectively ensuring it can't be passed in the current session. He says the Government prefers to tackle the Tottenham Court Road problem via existing legislation instead.

. September 15, 1887: Christian World recalls the transfer of St Christopher-le-Stock's sacred soil back in 1780, asking whether this means the Tabernacle's burial ground now qualifies as consecrated land. If so, any change in its use would legally require permission from the Anglican church, which clearly hasn't been given in this case. Simply grant it's consecrated ground, the paper argues and "the Bishop of London could, without more ado, put a stop to the present scandal".

. October 14, 1887: Plake returns to court, complaining that Hall has replaced the roundabout's original 18ft booth with a 14ft one, which blocks his light just as badly as before. Hall argues that it was only the original 18ft booth he'd been ordered to remove and that he'd taken that one to Hammersmith, so what's all the fuss about? The judge declares this "a most impudent contempt" of court and gives Hall two days to remove the new tent if he doesn't want to go to prison. Hall meets the court's deadline and the contempt charge is purged.

. October 31, 1887: Frederick Temple, the Bishop of London, writes to Gaze, replying to his query about whether the burial ground's possible consecrated status allows him to act. "I directed enquiry to be made into my legal powers of interference and communicated with the Home Office on the same subject," Temple says. "I am sorry to say I find myself quite powerless to aid you." (35)

. November 15, 1887: The Tabernacle holds an event to celebrate its 131st anniversary. "The sacred edifice was filled with a large congregation who, with the speakers, were much disturbed by the unseemly noises coming from the adjacent burial ground," the St Pancras Gazette reports. "The continuous grinding of a steam organ attached to the roundabout was the principal, but this, bad though it was, was not nearly so intolerable as a shrill whistle which announced the commencement or finish of every 'go'. It was this latter feature which distracted the attention." (36)

You could forgive the chapel trustees for despairing at this point. Five months on from the fair's arrival and with so much effort expended, they still found themselves besieged by just as much noise and nuisance as ever. As the New Year approached, though, their luck was just about to change.

The first gleam of light for the chapel's trustees came on December 9, 1887, when their attempt to extend the terms of the existing injunction finally reached court. As well as banning the fairground from operating during its Wednesday night services, they hoped to stop it using the burial ground in any way that interfered with lessons, meetings or concerts in the chapel's school room. "The plaintiffs complain, particularly of the merry-go-round, that the entertainment is of such a noisy character as to prevent the reasonable use of the schoolroom for the purposes to which it is applied," explained the Times. (37)

The first gleam of light for the chapel's trustees came on December 9, 1887, when their attempt to extend the terms of the existing injunction finally reached court. As well as banning the fairground from operating during its Wednesday night services, they hoped to stop it using the burial ground in any way that interfered with lessons, meetings or concerts in the chapel's school room. "The plaintiffs complain, particularly of the merry-go-round, that the entertainment is of such a noisy character as to prevent the reasonable use of the schoolroom for the purposes to which it is applied," explained the Times. (37)

The three defendants were named as Jacobson, Hall and a Mr Beach, who handled day-to-day management of the burial ground's rides. They persuaded Mr Justice North to put the case on hold for a week by agreeing immediately to move the merry-go-round further from the Tabernacle building, and to close the rifle range during school hours and in the early evening.

The case resumed on December 22, when North granted the chapel an injunction banning any entertainment after 6:30pm which was a nuisance to the schoolroom. In return, the trustees agreed not to use the schoolroom on Boxing Day and confirmed that any entertainments running on the site that day could proceed with no objection.

"We have gained all for which we could possibly hope," they wrote in January 1888's Good Company magazine. "It is evident the show has been dependent for its success on the noise that has disturbed us. That noise we will now have the power to stop and the rough folk who have hitherto been attracted will certainly not be tempted nearly so strongly by any milder or more reasonable form of entertainment."

Even now, Hall could not resist pushing his luck. He was back before North again on February 24, this time on charges of breaking the new injunction. Prayers and temperance meetings at the Tabernacle were still being disrupted by the fairground's noise. "The services were interrupted by lively and catching airs from a steam organ, while ladies were alarmed during the prayer meetings by the noise of rifle shooting", reported that day's Echo. The Chronicle had its own list of disturbances, including "the throwing of sticks at coco-nuts, many of the sticks beating against the school wall". (38, 39)

Hall's defence this time was that he'd been sub-letting the burial ground to an associate called Charles Pressland since late last year - sometimes he said November, sometimes December. If there was still trouble at the site, then it was Pressland who must be blamed for it, not him. Pressland went along with this account, secure in the knowledge that he hadn't been named in the injunction and so couldn't be punished for breaking it. North didn't believe a word of this. He said Hall was plainly the one responsible for the continuing racket, pointed out that he'd been unable to keep his story straight from one minute to the next, and committed him to Holloway Prison forthwith. If ever there was a case in which a man ought to be sent to prison for breach of an injunction, North said, this was it. Given half the chance, he told Pressland, he'd have had him locked up too. (40)

Holloway's gates slammed shut behind Hall on February 25 and that's where he remained for the next month. North refused to free him till the end of March, following Hall's abject apology for his contempt of court. Tugging on the judge's heartstrings, he claimed he had a crippled wife and several children relying on him. He insisted again that it was Pressland now operating the fairground, not him and swore to do all he could to curb any continuing nuisance there.

Meanwhile, London's Metropolitan Board of Works - soon to be replaced by London County Council - was still looking for a more permanent solution to the problem. Prompted by a letter from Home Secretary Henry Matthews, the board's William Wetenhall agreed in principle to make a compulsory purchase of the burial ground's land and turn it into a public garden. If St Pancras Vestry came up with half the money for this, he said, the board would match it - but only if a far lower purchase prices than the suggested £10,000 could be negotiated. His own preference, he added, would be for Levy-Lawson's Bill to tackle the situation via its ban on temporary structures. But when Levy-Lawson reintroduced his Bill to Parliament in March 1888, it got no further than its first reading.

A June 1888 murder trial involving two rival London gangs revealed that the defendants had met at the Tottenham Court Road fairground before heading west to find their victim, and fled straight back there after the crime. The spot was a regular hangout of theirs, but also what one of their defence lawyers called "a miniature hell". Questions were asked in the House of Lords, where Earl Brownlow admitted the site was "the resort of bad characters and tended to the increase of crime in the locality". (41)

The logjam over funding the burial ground's purchase finally broke on July 5, 1888, when the chapel's trustees at last signed a deal with the site's freeholder. The price agreed was £3,500, this money to be raised via a mortgage loan. Two people who held mortgages of their own on smaller sections of the burial ground would have to be bought out too.

In February 1889, North granted another nuisance injunction against the fairground's operators, this time for operating a switchback ride on the site. Later that year, the chapel trustees discovered the building itself was collapsing, undermined by both the soggy ground it had been built on and the many burials beneath its floor. It would take a decade to put matters right there - and another major fundraising campaign - during which time services had to be held in a temporary iron building next door.

The burial ground's purchase was completed at last in June 1890, when the Pall Mall Gazette put the total price paid for it at £4,000. The chapel's minutes from that year tell us that the freeholder's side of this deal was signed by Maurice Jacobson, Nathan's oldest son, who seems have gone into business with the widowed Annie, his stepmother. The 1891 census shows Annie as head of a household in central London's Little Titchfield Street, where Maurice, Charles, Rebecca Jr and Julius also live. To that extent, at least, the family must have reconciled. Both Maurice and Annie describe themselves as dealers in works of art, which suggests they were running Nathan's old business together. (42)

By the beginning of July 1890, the chapel had received London County Council's letter confirming the compulsory purchase plans and offering the trustees £4,500 for the burial ground site. The trustees agreed and British property law's sluggish gears creaked into motion once again, contracts finally being exchanged in November 1893. (43)

The original idea had been for St Pancras Vestry to meet half the cost of the burial ground, LCC chairman John Hutton explained, but in the event that cash had never materialised, leaving the council to find the whole sum itself. It was also left to the LCC to pay the £633 needed to convert the half-acre site into its long-promised public garden. Council workmen tarmacked over the burial ground's central areas to provide a playground, installed benches on either side and planted all the edges with shrubbery. It was named Whitfield Gardens - a variant spelling of its founding preacher's surname - and officially opened by Hutton on February 16, 1895. The southern burial ground was landscaped to match at about the same time. (44)

We fast-forward now to 1940 and to the height of the London Blitz. Tube stations all over the city were pressed into action as bomb shelters, but could not do the job on their own. After serious civilian casualties at both Marble Arch and Bank stations, work began to build ten new deep-level shelters nestled beneath the Tube's Central and Northern lines - one of them at the front end of Whitfield Gardens' northern section. You can still see the graffiti-daubed walls of its surface structure there today.

We fast-forward now to 1940 and to the height of the London Blitz. Tube stations all over the city were pressed into action as bomb shelters, but could not do the job on their own. After serious civilian casualties at both Marble Arch and Bank stations, work began to build ten new deep-level shelters nestled beneath the Tube's Central and Northern lines - one of them at the front end of Whitfield Gardens' northern section. You can still see the graffiti-daubed walls of its surface structure there today.

The new shelters, set 100 feet deep in the earth, were completed in 1942. "[They] each comprised a pair of parallel tunnels, 1,200 feet long, divided into upper and lower floors and equipped with iron bunks," Stephen Smith writes in his 2004 book Underground London. "There were also sickbays, wardens' posts and enough ventilation equipment to bring air to these subterranean hideaways." (45, 46)

Three years later, as the war began drawing to a close, the problem was no longer Luftwaffe raids, but Hitler's V2 flying bombs. On March 25 that year, the radio announcer Stuart Hibberd was working at BBC Broadcasting House in Portland Place. At about 10:30pm, he left the studio where he'd been broadcasting and headed upstairs to the fifth floor office he shared with a colleague called Joseph McLeod. (47)

"As I entered, there was a heavy explosion and the French windows moved suddenly in and out with the blast as a V2 fell quite near," Hibberd later wrote. "We both rushed out on to the balcony and from there we could see a huge mushroom of smoke and sparks rising up half a mile high, a little to the east of us. Then came the inevitable clanging of bells as the fire engines and ambulances dashed to the spot, which turned out to be Whitefield's Tabernacle in the Tottenham Court Road, used during the war as a hostel.

"I walked round there the following week and saw the severe damage that had been done to the surrounding buildings: there was a pile of rubble some thirty feet high and through it stuck out six iron pillars - all that remained standing of the original Tabernacle." This blast made the chapel the last major casualty of the whole V2 campaign and, once again, its trustees were forced to rebuild. (48)

Five houses immediately south of the old burial ground were also destroyed by the explosion, creating a large open space which the Procter family donated as an extension to Whitfield Gardens. Three of the family's 19th century ancestors had been buried in Whitefield's graveyard, so the Procters erected a memorial stone to them in the space they'd just donated. It's still there today: a flat, stretched pyramid now lying in the shadow of Mick Jones' 1980 mural showing people from the neighbourhood.

Whitefield's Tabernacle is now home to both the American International Church and the London Chinese Lutheran Church, both of which still hold regular services there and work to help the surrounding community. The theatrical connection started by David Garrick continues too, with the Royal Shakespeare Company often renting space at the Tabernacle when it needs a London rehearsal room.

The northern part of the old burial ground is now owned partly by Transport for London and partly by the London Borough of Camden, which hosts a community nursery and playground there. Whitfield Gardens remains intact on the other side of the chapel, where it provides a pleasant spot for office workers to eat their lunchtime sandwiches and a handy cut-through for tourists on their way to explore Fitzrovia. Most importantly of all, it's now something of a haven for the area's homeless, who know it's one of the few public spaces left in London where they'll be left to gather, chat or sleep in peace. You'd be hard-pressed to find one in a thousand Londoners today who have any notion the site was once a graveyard - let alone that its half-consecrated soil once held a young woman laid to rest with a silver pin pressed deep into her heart.

Many thanks to Jonathan Miller, community pastor at the American International Church, who gave me access to the Tabernacle's 19th century records and supplied the two vintage photographs you see above. I couldn't have written this essay without his help.

October 2019: A few weeks after I posted this essay, Jonathan contacted me to say his own continuing research had uncovered a surprising link between Whitefield's Tabernacle and Karl Marx. He sets out his findings on this PlanetSlade letters page.

Appendix: Jenkins the giant.

William Jenkins, an 18th century clerk at the Bank of England, had good reason to fear the body snatchers who then prowled London's graveyards. He was close to 7ft tall and he knew this meant the city's anatomists would pay a premium price to anyone who cared to dig up his cadaver. Just look what had happened to Charles Byrne.

Byrne, a 7ft 7ins colossus known as the Irish Giant, had died in 1783, his mind full of the same fears which now beset Jenkins. Despite Byrne's express arrangement with friends that his body should be sealed in a lead coffin and buried at sea, the anatomist John Hunter managed to bribe one of the men transporting it to deliver the cadaver to him instead. It cost Hunter at least £130 (some say as much as £500) at a time when only about 6% of families earned over £100 a year. (49)

He reduced Byrne's body to its skeleton and, four years later put it on display in his own Hunterian Museum. You can still see it today at London's Royal College of Surgeons, where it continues to provide precisely the post-mortem freakshow exhibit Byrne had prayed he'd never become.

Jenkins was determined to prevent this happening to him. He knew that the Bank's Garden Court occupied land that had once been St Christopher-le-Stocks' graveyard, so he got special permission from the Governors to have his body buried there when the time came. That promise was duly honoured in 1798, when Jenkins' body was laid in an 8ft coffin and laid to rest in Garden Court. "Upwards of 200 guineas had been offered for his corpse by the surgeons," The Hereford Journal reported. (50)

The body remained undisturbed until 1923, when further redevelopment at the Bank led to his coffin being moved to the catacombs at Nunhead Cemetery. "The fate that William tried so hard to avoid finally came to pass in the 1970s," The London Dead blog says. "Thieves stole the coffin from the abandoned cemetery for its scrap value and scattered his remains on the floor of the catacomb. They were presumably cleared up and disposed of, quite where no-one knows." (51)

Sources

1) Kentish Gazette, November 8, 1808.

2) The parish council's report is reproduced in full in John Nelson's History of Islington (1811). It was stumbling across his book in my local Oxfam shop which sparked this whole essay.

3) Plenty of other coroner's juries at around this time recorded verdicts of murder. If the Islington jury had thought that was what happened to Elizabeth, it was perfectly free to say so.

4) Author's correspondence with Nicholas Rheinberg, April 2019. "In previous centuries coroners' juries could return somewhat exotic verdicts," he told me. "I have in my records details of a 14th century inquest where a poor farmer was struck by lightning and killed. The jury returned a verdict that he had died 'by the contrivance of the devil', a rather more blood-curdling verdict than 'accidental death' or 'act of God'."

5) In an earlier version of this drawing, called Enthusiasm Delineated, Hogarth includes Whitefield as a second preacher in the chapel. A howling dog beneath his lectern has Whitefield's name attached to its collar. Neither of these elements survive in the Credulity, Superstition & Fanaticism print, but it does include a couplet from a Methodist hymn which it attributes to Whitefield ("Only love to us be given / Lord we ask no other Heaven") and a congregant's book titled "Whitefield's Journal". The chapel in the final print is packed with figures from the era's most popular myths, including Mary Toft, the Boy of Bilson and the Cock Lane Ghost.

6) Biographical essay on Whitefield, www.christianitytoday.com.

7) Quotes taken from Benjamin Franklin's autobiography (Oxford University Press, 2008).

8) The carpenter who helped build Whitefield's Tabernacle also worked for Garrick at the Drury Lane Theatre. According to Richard Ryan's 1825 book Dramatic Table Talk, Whitefield ran out of money during the chapel's construction and was unable to settle the carpenter's bill. When Garrick heard about this, he not only gave the carpenter an advance to tide him over, but also gave Whitefield £500 so work at Tottenham Court Road could continue.

9) George Whitefield: America's Spiritual Founding Father, by Thomas S. Kidd (Yale University Press, 2014).

10) "In 1832 there were persons living who remembered when the last house in London was at the corner of Whitefield's Tabernacle," the Globe reminded its readers in December 1887. By that time Tottenham Court Road had become one of the busiest streets in London, of course.

11) I like to think that Goodson had been pinching coins from the collection plate and God decided to go old-school in punishing him. Zzzap!

12) Most tellings of this story assume Whitefield himself was responsible for stealing the consecrated soil but, as we've seen, the dates make this quite impossible. The ultimate source for the story is Timbs and he never links it to any particular individual. St Christopher-le-Stocks was demolished in 1780, right in the middle of Joss's 1770-1797 ministry at Tottenham court Road, so I've attributed the stolen dirt scheme to him instead.

13) Curiosities of London, by John Timbs (David Bogue, 1855).

14) Pall Mall Gazette, July 9, 1886.

15) London County Council Survey of London Vol XXI: Tottenham Court Road & Neighbourhood (published 1949).

16) The Gentleman's Magazine, March 1776.

17) The Diary of a Resurrectionist 1811-1812, by James Blake Bailey (Swan Sonnenschein, 1896). The pub Naples used in Southwark was The Rockingham Arms, and there's still a pub of that name in the Borough today."

18) All the ages given here and in subsequent census information are approximate. Jacobson and his family often gave themselves a different year of birth from one census form to the next, not for any sinister reason, but simply because they wouldn't have been sure which year was right. Few people at this time had any firm evidence of their own birth date, so most just guessed.

19) All the trial details here are taken from the Old Bailey's online transcript: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/

20) The London Encyclopedia, edited by Ben Weinreb & Christopher Hibbert (Macmillan, 1993).

21) Old Bailey transcripts: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/

22) Whenever adjusting 19th century sums of money, I've used the Bank of England's online calculator: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator.

23) I've missed out the 1861 census because it shows Jacobson (then calling himself "Nathan Woolf") as a house guest at his parent's place in Whitechapel. No other details of his own family appear.

24) Rouch and the other witnesses' accounts of what they'd seen at the burial ground were reported at length in that month's newspapers. Two of the main ones I've used are the Sheffield & Rotherham Independent (April 2, 1880) and the London Daily News (April 13, 1880).

25) Porcelain teeth were being made for use in dentures by this time, but many still considered recycled human teeth a better alternative. "What dentists wanted more than anything was a steady supply of human teeth," New Scientist wrote in June 2001. "They could never get enough, so prices were phenomenal. [.] The biggest purveyors of teeth were the 'resurrectionists' who stole corpses to sell to medical schools. Even if they dug up a body too far gone for the anatomy classroom, they could still pocket a tidy sum by selling the teeth."

26) London Daily News, July 1, 1880.

27) Liverpool Mercury, July 2, 1880.

28) London Evening Standard, December 21, 1880.

29) Some original court papers from Jacobson v Jacobson can still be viewed at the UK's National Archives in Kew and that's where I found these details. Wingard's name is given in the list of plaintiffs along with those of the five Jacobson children who were suing, where he's described as "their near friend'. I can't be sure what his role was in the case, but the oldest of the five children was only 14 at the time, so it's logical to assume they'd have needed an adult to organise it all.

30) Dr Ian Williams, a History of Law professor at UCL, told me that the Chancery division's involvement suggests there was a Jacobson family trust somewhere in the mix here. "The Chancery could order the trustees to act in particular ways and make rulings about the entitlements of particular family members," he explained. "This could require continuing intervention by the court, especially if family members were feeling litigious."

31) Scrabbling around for info on Monsieur Bihin, I came across an 1854 press clipping revealing that he'd once been tried for killing a man. The Quebec Chronicle of September 19 that year reported that a man called Thomas Flanagan "was slain in Saturday night last by Mons. Bihin, the French [sic] Giant, while attempting to force his way into the house at which the latter was staying". The Paris jury declared this to be Justifiable Homicide and Bihin walked out a free man.

32) St Pancras Guardian, July 2, 1887.

33) My guess is that the "active gentleman" was Harry Gaze. He seems to have been the most energetic of the trustees through their whole campaign.

34) The Echo, August 29, 1887. (The City Press clipping is undated.)

35) Christian World published the bishop's reply in its November 10, 1887 edition.

36) St Pancras Gazette, November 19, 1887.

37) The Times, Dec 22, 1887.

38) The Echo, February 24, 1888.

39) The Chronicle, February 25, 1888.

40) Holloway housed both male and female prisoners at this time. It went all-female in 1903.

41) Francis Cole, a teenage member of the Fitzroy Place Boys gang strayed into Marylebone one May evening in 1888, where the local thugs beat him up and blacked his girlfriend's eye. Next night, he returned for revenge with seven friends in tow, one of whom stabbed a random Marylebone lad called Joseph Rumbold dead with an eight-inch knife. George Galletly, the killer, was found guilty of murder but escaped the death penalty because he was only 17 years old. As I write this in 2019, identical crimes are happening every week in London, the only difference being that both the killers and their victims are even younger.

42) Annie was only a year older than Maurice and there was no blood relationship there. I wonder if they became a couple?

43) LCC chairman John Hutton later said they'd paid £5,000 for the site.

44) All that remained was to wrap up Jacobson v Jacobson, which finally came to close in November 1905.

45) Underground London, by Stephen Smith (Little Brown, 2004).

46) "[The shelter building] next to the church is part of the same complex as the Eisenhower Centre in Chenies Street, but it's now used only as an emergency exit and ventilation shaft," American International Church minister Jonathan Miller told me in 2019. "There's a brief snippet in the church's minutes from the 1950s complaining about troop movements in and out disturbing the Sunday service!"

47) The V2 campaign began in September 1944, hitting London with 1,358 rocket bombs before it was done. It's estimated that 2,754 civilians were killed by V2 strikes in London alone.

48) This - is London, by Stuart Hibberd (Macdonald & Evans, 1950).

49) The Value of Money in Eighteenth Century England, by Robert D. Hume (Huntington Library Quarterly, vol 77 no. 4).

50) Hereford Journal, April 11, 1798.

51) The London Dead, Oct 22, 2016: https://thelondondead.blogspot.com/