For bereaved Londoners in 1850, finding a cemetery where their loved ones could be left to rest in peace was no easy matter.

For bereaved Londoners in 1850, finding a cemetery where their loved ones could be left to rest in peace was no easy matter.

The capital's population had more than doubled in the first half of the 19th Century, and the number of London corpses requiring disposal was growing almost as fast. But cemetery space in the city had spectacularly failed to keep pace. This led to graves being desecrated and re-used with alarming regularity, disinterred bones left scattered across the churchyard grass and a greatly-increased risk of disease as material from decomposing bodies leaked into nearby drinking wells and springs. Matters finally came to a head with the cholera outbreak of 1848-49, which killed nearly 15,000 Londoners and made it clear that drastic action was needed.

The man who came up with the answer was Sir Richard Broun. In 1849, he proposed buying a huge tract of land at what is now the Surrey village of Brookwood to build a vast new cemetery for London's dead. The 2,000-acre plot he had in mind - soon dubbed “London's Necropolis” - was about 25 miles from the city, which meant it was far enough away to present no health hazard and cheap enough to allow for affordable burials there. The railway line from Waterloo to Southampton, Broun realised, could offer a practical way to transport coffins and mourners alike between London and the new cemetery.

The idea of using the railways to link London to the new rural cemeteries it so obviously needed had been in the air for some years when Broun presented his plan, but not everyone was convinced. Many thought the clamour and bustle they associated with train travel would not suit the dignity demanded of a Christian funeral.

There were other fears too. In 1842, questioned by a House of Commons Select Committee, Bishop of London Charles Blomfield said he thought respectable mourners would find it offensive to see their loved one's coffins sharing a railway carriage with those of their moral inferiors. “It may sometimes happen that persons of opposite characters might be carried in the same conveyance,” he warned. “For instance, the body of some profligate spendthrift might be placed in a conveyance with the body of some respectable member of the church, which would shock the feelings of his friends.”

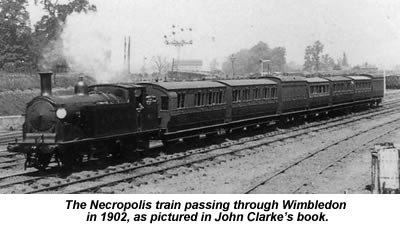

Such objections sound foolish to modern ears. But it is worth remembering that, in 1842, train travel itself was still a novelty. George Stephenson had introduced the first regular passenger service as recently as 1830, and it was probably inevitable that extending this noisy innovation to funeral traffic would prove controversial. John Clarke, author of The Brookwood Necropolis Railway, says: “Train travel was still seen as revolutionary. The first through train from Waterloo to Southampton ran in 1838, which is the date of that route being fully opened. Waterloo itself was only completed in 1848, and the first Necropolis Station came along just six years after that. Arguably, at that time, it was a major addition to the service.”

Andrew Martin, who researched the funeral trains while preparing to write his thriller The Necropolis Railway, adds: “When trains first came along, people had a very different attitude. Trains were regarded like cars are now, really. People were scared of them, they were thought of as dirty, noisy things. That was a very mid-Victorian attitude. Dickens hated trains.”

Despite this suspicion of rail travel, MPs took Broun's idea seriously and, in June 1852, they passed an Act of Parliament creating The London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company, a name which was later shortened to The London Necropolis Company. London & South Western Railway became LNC's partners in the scheme, and looked forward to making an estimated £40,000 a year from the extra fares they believed the service would produce. LNC bought two thousand acres of Woking Common land from Lord Onslow, and set aside 500 acres of that for the cemetery's initial stage.

Even with all this in place, however, several delicate problems remained to be solved. L&SWR's shareholders had already decided that they did not want the passenger stock they were lending to LNC mixed up with the carriages used on their mainstream passenger services. If L&SWR's existing customers suspected they were being asked to travel in carriages which had earlier been hooked to a funeral train, the directors feared, they would stay away in droves. It was decided, therefore, that the Necropolis trains would have to be run as an entirely separate service, with its own dedicated rolling stock and timetable.

The Bishop of London's objections were addressed by ensuring that every Necropolis train would offer six distinct categories of accommodation, and that dead passengers would be given just as wide a choice as their live companions.

The first distinction was between conformist funeral parties and non-conformist ones. In a train carrying two hearse cars, for example, one would be reserved for the Church of England's dead, and the rest for everyone else. The passenger carriages would be allocated on the same principle, and each hearse car yoked to the appropriate passenger section. Following this idea through, LNC took care to plan for two stations at Brookwood. One would serve the conformist area on the sunny south side of the cemetery, the other the chilly non-conformist graves on its north side.

The second distinction depended not on what religion you were, but on whether you bought a first-class, second-class or third-class ticket. As with train travel today, each class offered a few more home comforts than the one below it, and each cost a great deal more than the last. Coffin accommodation was divided into three classes too, with each hearse car split into three sections of four coffin cells each. LNC justified the higher fares it charged for first-class coffin accommodation by pointing to the higher degree of decoration provided on its first-class coffin cell doors and the greater degree of care which first-class coffins were given at both ends of the journey.