Thomas Wright, a West London barrister, came home from his Lincoln's Inn chambers one evening in January 1904 to find a mob of treasure hunters wrecking his front garden. One of them had already dug down to the base of the garden railings and was busy trying to dislodge them to see if a £50 medallion had been buried beneath. Glancing up and down Westbourne Terrace, Wright could see that many of his neighbours' gardens had been invaded too. This had been going on for four days.

Thomas Wright, a West London barrister, came home from his Lincoln's Inn chambers one evening in January 1904 to find a mob of treasure hunters wrecking his front garden. One of them had already dug down to the base of the garden railings and was busy trying to dislodge them to see if a £50 medallion had been buried beneath. Glancing up and down Westbourne Terrace, Wright could see that many of his neighbours' gardens had been invaded too. This had been going on for four days.

Wright waded in, grabbed one of the ringleaders from his own garden by the collar and started dragging him towards the nearest police station. But the mob immediately closed around him, blocking Wright's path and insisting that he let the man go. When he refused, they began jostling him. Some helped Wright's captive slip out of his coat and escape, cheering him on as he fled the scene.

Even if Wright had been young and fit enough to give chase, the mob was not going to allow it. Fearing for his safety, he took refuge in the nearest house, where the owner allowed him to remain until two policemen arrived on the scene about ten minutes later. Wright gave them the captured coat, they escorted him safely to his own front door, and the night's ordeal was over.

We know all this because Wright sat down next morning and described the episode in a letter to The Times. “From early on the 10th inst., down to today, the 14th, from morning to night, and even in the night, these thoroughfares have been infested by crowds of people watching for, and finding, opportunities in digging up the private roadways and gardens in searching for the treasure,” he said.

“Westbourne Terrace and Gloucester Gardens have been most seriously damaged, and the streets are still beset with gangs of idle people bent either upon doing further mischief or enjoying the pleasure of seeing other doing it” (1) .

Wright's attackers were looking for one of several hundred prize medallions which a couple of Sunday newspapers had planted around the UK - most likely those from the Weekly Dispatch. The paper used its first issue of the New Year to announce it had concealed 177 treasure medallions, the most valuable of which were worth £50 apiece. Each issue would carry a series of clues pointing to the prizes' locations. That meant, of course, that anyone hoping to find one of the medallions had to buy a copy of the Dispatch first – and perhaps its special supplements too.

By January 17, the total prize money on offer had reached £2,000. Twenty £50 medallions were hidden in London, giving the capital a total of £1,000, and the rest in Manchester (£500), Reading (£50) and nine other English towns. The scheme added another £1,790 in prizes before the end of the month, bringing the total to £3,790, and stretching its reach as far afield as Leeds, Belfast, Norwich and Cardiff. Ten pounds in 1904 had about the same purchasing power as £900 has today, so even the humblest medallions were well worth finding.

Three days after Wright's letter appeared, his neighbourhood was still under assault, with big crowds of treasure hunters gathering less than half a mile from his home. At lunchtime on January 18, a 19-year-old Battersea labourer called Frederick Nurse was arrested in Blomfield Road. He had been digging at the roots of a tree there with a carpenter's gouge. When challenged by PC Ford, Nurse explained that he was “looking for the buried treasure”.

Reporting next day's proceedings against Nurse in Marylebone Magistrates' Court, The Times said there had been “hundreds” of other treasure seekers in Blomfield Road at the time, digging at the roadway and trespassing wherever they pleased. Paul Taylor, the magistrate, said substantial damage had been done to the highway by “this most unbearable nuisance” and fined Nurse 40 shillings (£2) with the alternative of a month in prison. Meanwhile, Clerkenwell magistrates were dealing with three similar offenders of their own, part of a treasure-seeking crowd big enough and rowdy enough to require the dispatch of extra police from King's Cross to control them (2) .

All over London, the story was the same. Crowds gathered outside Pentonville Prison and Islington's Fever Hospital, blocking the roads and attacking any scrap of loose ground. Hundreds of treasure seekers converged on a Bethnal Green museum and began digging there. One Shooters Hill resident said his area was “infested with gangs of roughs”. Shepherd's Bush, Clapton and Canning Town were besieged too.

By the time Nurse had his day in court, Luton and Manchester had also been hit. Luton residents seeking the town's single £10 medallion caused what councillors called “a gross disturbance” to the town in the early hours of Sunday, January 10. A week later, the Manchester Evening News found “some most extraordinary scenes” in its own city.

“From an early hour on Saturday night to late on Sunday night, various parts of the Manchester suburbs were the resort of men, women and children, people of all classes, drunk and sober, who had taken up what they thought to be the real clue to the spot where a medallion worth £25 lay hidden beneath the turf,” the MEN reported. “They seized upon vacant pieces of land and stretches of roadway, digging and delving until not a foot of the ground lay smooth.” In Blackley, it added, three hunters had arrived simultaneously at the same spot and “settled the matter by a three-cornered fight” (3).

Wherever the Dispatch's promotion touched down, hysterical treasure hunters began tearing up the public highways with knives, shovels, sticks and any other implement that came to hand. If they took it into their head to dig up a private garden or vandalise the local park, they went right ahead and did so. Anyone who protested was bullied into submission, just as Wright had been. The promotion was less than three weeks old, and already causing chaos.

The seeds of all this trouble had been sown six months earlier when Tit-Bits, a rival weekly had unleashed a brand new circulation gimmick.

The seeds of all this trouble had been sown six months earlier when Tit-Bits, a rival weekly had unleashed a brand new circulation gimmick.

The 1890s and 1900s were a turbulent time for British newspapers, pulling together several big social changes which suddenly meant a high circulation was essential for any paper that wanted to survive. The introduction and rapid growth of the railways had made national distribution a much more practical proposition, and increasing literacy rates meant there was a vast new audience out there to be reached. Workers were moving from the countryside to the cities – again making distribution easier – and new technology was making bigger print runs affordable.

This led to the launch of a new wave of popular newspapers, including the Daily Mail in 1896, the Daily Express in 1900 and the Daily Mirror in 1903 (4) . The new readers they wanted to reach demanded shorter, snappier news stories, plus plenty of human interest, sport and gossip. They couldn't afford to pay much for their newspapers, so cover prices had to be low. Publishers needed to increase advertising revenue instead, and that meant delivering the high circulation figures which potential advertisers demanded. Many papers decided the best way to pull in new readers was to bribe them with cash competitions (4) .

There was no arguing with the success this new economic model produced. Four years after its 1896 launch the Mail had increased circulation from an initial 400,000 to a ground-breaking one million readers, making it the UK's top seller (5) . Any newspaper which wanted to keep a hold on the popular market was going to have to fight back hard, and that meant launching cash competitions of its own.

The first treasure hunt competition was launched by Tit-Bits, another relatively new publication. Launched in 1881 to provide a weekly miscellany of short, easily-digested items, the paper racked up a circulation of over 300,000 in less than a year. Its June 20, 1903, issue carried the first instalment of Hidden Not Lost, a detective story featuring two characters endlessly discussing the clues they had uncovered to finding a £500 bag of gold sovereigns hidden somewhere in Britain.

Each weekly issue contained another instalment of the story, packed with more clues. Anyone solving them would be guided to a real location, where a real £500 bag of sovereigns was hidden. That prize was found at the end of August, and Tit-Bits immediately launched a sequel.

The new story, Gold in Waiting, had a Holmes-and-Watson duo called Pike and Meggs chasing round the country trying to prevent a royal murder plot. The dastardly villain, Count Tabritz, had selected ten spots around England where his intended victim might be vulnerable. At each of these spots, he buried £100 in gold sovereigns to pay the hired assassin he planned to use. Pike and Meggs uncovered clues to each location in turn, which readers were invited to solve in their search for one of the ten prizes. In an ingenious twist, Tit-Bits' man concealed each real £100 stash by packing the sovereigns into a pointed metal tube and banging it into the ground with a mallet.

Gold in Waiting, which began in the September 12, 1903, issue, proved an immediate hit. On October 10, Tit-Bits announced the first £100 tube had been found by George Brown, a London journalist, who followed the story's clues to Turpin's Pond in Epping Forest. By Christmas, just one of the original ten tubes remained undiscovered.

It's only when you look at how much work the Tit-Bits clues required to solve that you realise just how determined the finders must have been. Take tube nine for example, which was eventually found by WJ Randall, the general manager of Manchester's Trade Protection Office.

Before he could secure his prize, Randall had to narrow down the possible cities to Newcastle and Carlisle, rule out Carlisle by deducing that Tabritz' foreign pronunciation of the city's “Citadel” station could be mistaken for “the hotel”, find a district of Newcastle that sounded a bit like “Edward Green” and realise that the serial number Meggs had overheard must be attached to a lamp post. He then had to go to the Newcastle suburb of Jesmond Dene, find post number 6594, work out where the tube was buried in relation to that post, return to the site after midnight and – finally – dig it up.

Randall was particularly proud of making the Edward Green/Jesmond Dene connection. “The clue appeared a very thin one,” he later confessed. “However, as I had previously obtained careful information regarding every other place in the British Isles which bears a name at all similar to 'Edward Green', and as I had struck all these names off my list one by one, Newcastle district only remained” (6) .

Few of Tit-Bits' readers would have been as hard working or as ingenious as Randall. But the clues clearly intrigued even those who made only the most token efforts to solve them, and the promotion was counted a great success. By the end of 1903, newspapers in Paris and America had launched treasure hunt promotions of their own. Austria would follow soon. The first British newspaper to copy Tit-Bits' idea was the News of the World, but the Dispatch was not far behind.

The Dispatch was a lively broadsheet, founded in 1801, which advertised itself as “the paper that grips the masses”. Acquired by the Mail group in 1903, it found itself fighting hard to retain its working class readership. New papers like the Mirror were targeting exactly the same people, and using every technical innovation they could to tempt Dispatch readers away. As 1903 drew to a close, the Mirror was just weeks away from becoming the first British newspaper to fill its pages with photographs. “See the news through the camera,” it boasted in a front-page box. “Yesterday's events in pictures” (7). Meanwhile, the Dispatch was still relying on line drawings. Something had to be done.

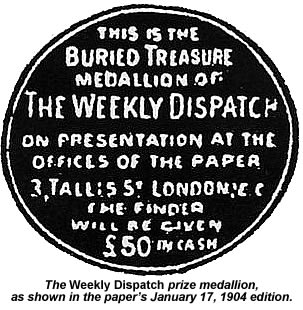

The precise beginnings of the Dispatch's scheme are a little hazy, but its first move must have been to mint up the initial batch of medallions. Each of these was a metal disc, about 6.5cm in diameter, with an inscription on one side. It read: “This is the buried treasure medallion of the Weekly Dispatch. On presentation at the offices of the paper, 3 Tallis Street, London EC, the finder will be given £50 in cash” (6). For the less valuable medallions, this £50 figure was replaced with “£20” or “£10”.

The precise beginnings of the Dispatch's scheme are a little hazy, but its first move must have been to mint up the initial batch of medallions. Each of these was a metal disc, about 6.5cm in diameter, with an inscription on one side. It read: “This is the buried treasure medallion of the Weekly Dispatch. On presentation at the offices of the paper, 3 Tallis Street, London EC, the finder will be given £50 in cash” (6). For the less valuable medallions, this £50 figure was replaced with “£20” or “£10”.

Dispatch staff were then sent out to bury these medallions close beneath the surface of public ground in 20 London boroughs and all across the UK. They noted each medallion's exact location, and prepared a series of elaborate clues describing the route they had taken to select its hiding place. They might mention, for example, “a spot where a square and a crescent stand side by side” or say they'd passed “a religious institution noted for its beautiful needlework”. These clues would be dribbled out bit-by-bit in the weeks that followed, with each journey requiring several instalments to complete.

The Dispatch launched what it called “The Greatest Treasure Hunt on Record” in its January 3, 1904, edition. “The published clues, if systematically followed up, will lead sooner or later to the spot where the treasure is concealed,” it promised, “And, in one or more cases each week, we shall indicate the exact situation of it.”

The first sign of trouble came a week later. January 10's Dispatch carried a clue saying North London's Islington medallion was hidden "near a place where people go against their will". This led to hundreds of readers gathering outside both the Fever Hospital in Liverpool Road and Pentonville Prison. The biggest crowds were outside the prison, where inmates must have been puzzled to see frantic diggers attacking any patch of loose ground.

"So great became the crowd at one time that no fewer than ten constables were called out to clear the road," the following Sunday's paper reported. "This was not the fault of the Weekly Dispatch, the too energetic hunters having altogether misunderstood the published clue, which had no reference whatsoever to Pentonville Prison" (8). The Islington medallion was eventually found just outside the graveyard attached to St Mary's church in Upper Street. No-one could argue that wasn't "a place where people go against their will".

The faint whiff of panic in the Dispatch's January 10 statement suggests the paper was already worrying that it might be held responsible for the damage its readers were causing. It had been careful to include a disclaimer in every issue pointing out that none of the treasure medallions were hidden on private property and that none required tools to unearth them. It soon became clear, however, that these disclaimers were passing most people by.

London and Manchester between them accounted for over half the medallions' total value, so those two cities were hardest hit. The crowds attacking likely spots were often hundreds strong, and came equipped with everything from corkscrews and tin openers to garden forks, crowbars and chisels. Professional men and well-dressed women fell prey to the craze just like everyone else. Some optimists, according to the Manchester Evening News, even gave up regular employment "to try and discover in a few days a sum which they could not honestly earn in as many months" (9). Others hoped to boost their income by more inventive means. A South Norwood man started selling magnetic forks which he claimed would adhere to any medallion they touched. "It is absolutely harmless," he said of his invention. "For it only leaves two small holes in the ground like a knitting needle". Hopeful forgers turning up at Tallis Street included one woman with a rusty bicycle sprocket, another with a piece of photographic glass plate and a group of four young men bearing a scrap of metal. Denied the £50 they wanted, the four men offered to settle for £1 instead (10).

Often, frustration led to violence. In Kensal Town Joseph George, a Notting Hill decorator, punched a canal official in the mouth when ordered to climb down from the bridge girders he had been searching. A counterfeiter caught placing fake discs in Stratford to confuse his rivals was forced to flee for his life. A drunk searching in Manchester's Dickenson Road after dark got annoyed with someone who stopped to mock his efforts and attacked them with a lamp.

Fourteen windows at the Dispatch's own Tallis Street offices were broken when frantic readers invaded the building to snatch early copies of the new edition. A boundary stone weighing three or four hundredweight was dislodged and thrown into the roadway in Hackney. So many people set about digging up Woolwich Common one night that it took soldiers on horseback to disperse them.

Islington and its surrounding boroughs - perhaps because of their proximity to Tallis Street - saw more action than most. A Dispatch reporter, sent to travel round London in the small hours one Sunday morning, found big crowds of treasure hunters already digging in Clerkenwell. A Kilburn man loosened a pressurised plug in the drain he was searching and narrowly escaped death when it shot past his head at high speed. One East End builder got so fed up with ejecting treasure hunters from his yard that he placed a notice on the gate pointing out that he'd searched the place himself and that "their ain't none".

By January 26, the Islington Gazette had seen enough, and that day's edition carried a powerful leader demanding the publishers responsible be called to account. "We have no sympathy with the class of people to prod roads and paths for the treasure," the Gazette thundered. "They deserve all they get from the Magistrates. But things are becoming serious when it is necessary to clear Woolwich Common by the aid of the military to prevent a fine open space being torn up with picks and shovels. [...] The actions of the public authorities ought to be against the enterprising newspaper proprietors who make the foolish their dupes and the ratepayers their victims" (11).

This was not a new idea. It had first been floated two weeks earlier, when Luton councillors wondered aloud how to tackle their own town's problems. But, faced with the awkward fact of the Dispatch's regular disclaimers, no-one seemed able to think of a practical way to target the paper. Several borough councils had asked their local magistrates to grant a summons against the Dispatch, but these were always turned down. Without a treasure hunter standing up in court to say his own vandalism had been directly prompted by the paper's promotion, magistrates said, any prosecution against the Dispatch was almost certain to fail. Therefore, issuing a summons would be pointless. Borough councillors protested that witnesses like this were almost impossible to find, but the magistrates would not budge.

This was not a new idea. It had first been floated two weeks earlier, when Luton councillors wondered aloud how to tackle their own town's problems. But, faced with the awkward fact of the Dispatch's regular disclaimers, no-one seemed able to think of a practical way to target the paper. Several borough councils had asked their local magistrates to grant a summons against the Dispatch, but these were always turned down. Without a treasure hunter standing up in court to say his own vandalism had been directly prompted by the paper's promotion, magistrates said, any prosecution against the Dispatch was almost certain to fail. Therefore, issuing a summons would be pointless. Borough councillors protested that witnesses like this were almost impossible to find, but the magistrates would not budge.

The first batch of treasure hunters to be arrested reached the courts in mid-January. Magistrates hearing these early cases were certainly bemused and frustrated by the crimes involved, but on the whole they tended to take a lenient attitude. As the cost of repairing the damage mounted, however, and the treasure hunters' enthusiasm raged on, the courts got tougher and tougher. Warnings were replaced by increasingly heavy fines, and the magistrates' comments became more withering by the day. Defendants were told to their faces that they were "silly", "stupid", "mad" or, in one case, "wandering lunatics".

On January 18, four men came before Mr Bros, a Clerkenwell magistrate, charged with damaging the turf and the roadway at Percy Circus, Holford Square and Claremont Square. Bros told them they had been "extremely foolish", but let them off with a warning. Next day, he dealt with Arthur Stuart, a 37-year-old architect caught damaging the surface of the roadway in Claremont Street. Bros told him: "You are an educated man. Does it not seem to you to be a very foolish thing that a man in his senses should be scraping about the roadway with a corkscrew? It seems to me to be the act of a lunatic. Go away" (12).

By January 27, magistrates' patience was wafer-thin. Archibald Freeman, described in The Times as "a respectable-looking man", had been arrested at 3:00am the previous day in Chelsea's Margaretta Terrace. He was digging a five-inch hole in the road with a (by then) broken knife. When they searched him, police found two newspapers and a notebook full of female names. One of the Chelsea clues had mentioned "a fair lady", and this prompted Freeman to investigate all the local streets with women's names. Margaretta Terrace was just one example.

This information produced some laughter in Westminster Magistrates Court, as did Freeman's insistence that he dug "in the mud in the gutters chiefly". Horace Smith, the magistrate, told him: "Of all the idle and contemptible folly I have ever heard of in the whole course of my life, this is about the worst. I cannot imagine how a respectable man like you can allow himself to do this kind of thing instead of his proper work in the world. It is folly and rubbish, and you are fined 20 shillings and the amount of the damage" (13).

All over London, the pattern was the same. Warnings gave way to fines of first 10 shillings, then 20 shillings, then the maximum 40 shillings available. The first 40 shilling fine - equivalent to about £180 today - went to Walter West, a commercial traveller brought before North London magistrates for digging at the kerbstones in Clapton's Almack Road with a garden fork. Mr d'Eyncourt, the magistrate, said: "This sort of thing seems to be spreading, not only all over England, but throughout Europe too. It is perfectly ridiculous that a man like this should do such a thing" (14).

Soon, 40 shilling fines were the norm. Then, magistrates in Westminster and Liverpool started muttering darkly about prison sentences without the option of a fine as being the next step. None of this did any good. No matter how heavy the fines imposed, or how great the threat of jail became, the crowds of treasure hunters remained as keen as ever. The Times reported that "thousands" of people had been digging on the canal towpath where Joseph George was arrested on January 17. A week later came the mass invasion of Woolwich Common, with 27 people convicted for that disturbance alone. Nothing seemed to deter them.

Anyone who doubted that had only to consider the scenes playing out every weekend at the Dispatch's Tallis Street offices. Every Saturday night, crowds would start to gather there at about 10pm, hoping to secure a good place in the queue for the early editions which emerged at 2am on Sunday. By midnight on Saturday, January 23, that queue was four abreast and long enough to fill half the surrounding streets. One of the people waiting was an unemployed young man called Walter Haynes, who had come out treasure hunting with his brother George. Armed with a first edition, they headed for their home turf of Bermondsey, getting there about 3am only to discover huge numbers of rivals already scouring the area.

Examining the other clues, George and Walter decided they knew exactly where the Wandsworth Common £50 medallion must be hidden. So, instead of going to bed, they set off on a seven-mile walk across London. When they got to Wandsworth, they found scores of other men already searching the common with candles and lanterns, but none who had hit on the precise spot. The brothers went straight to it and, five minutes later, had the medallion in their hands (15). From the City to Bermondsey, to Wandsworth Common and then back to Bermondsey again, all on foot and all at dead of night: men like these were not going to be discouraged by the prospect of a fine.

If the courts could not deal with the problem, then perhaps it was time for Arthur Balfour's Conservative government to step in. The Manchester Evening News gave Aretas Akers-Douglas, Balfour's Home Secretary, a stern warning. "It is recognised that the mere chance of being convicted of trespassing will not suffice to deter the majority who think it is worth while to join in looking for the money," the paper said. "If Mr Akers-Douglas pleads that he does not possess powers to deal adequately with the state of affairs lately created, he will be told very emphatically that it is high time he sought to obtain them." This righteous outrage did not stop the MEN running a lucrative ad for the Dispatch's Manchester hunt a few pages later in the same edition (16).

Government action finally came on January 29, when Earl Desart, the Director of Public Prosecutions, wrote to "the proprietors of certain newspapers which advertise hidden treasure" warning them to close the schemes down. If this was not done, he said, the Attorney General would get an injunction against them for causing a public nuisance. It seems safe to conclude that the Dispatch was the main paper he had in mind (16).

Government action finally came on January 29, when Earl Desart, the Director of Public Prosecutions, wrote to "the proprietors of certain newspapers which advertise hidden treasure" warning them to close the schemes down. If this was not done, he said, the Attorney General would get an injunction against them for causing a public nuisance. It seems safe to conclude that the Dispatch was the main paper he had in mind (16).

Tit-Bits, which still had one of Gold in Waiting's sovereign tubes left buried, staved off any further Government threat by dropping its own treasure hunt immediately. Its January 30 issue carried a long feature explaining that the final £100 had been hidden at the Meriden Cross near Solihull - a site which was supposed to mark the exact geographic centre of England. There's nothing in Tit-Bits to suggest the final tube had already been found by that time, and we don't know what finally happened to it. Presumably, it was either recovered by the reporter who had put it there, or gratefully nabbed by whichever reader happened to be closest to the Meriden Cross when the January 30 issue came out.

Much of Tit-Bits' feature was devoted to explaining how very, very responsible the paper had been in placing its own booty and stressing that its own readers had caused no vandalism at all. Describing his trip to the Meriden Cross, the paper's anonymous hider said: "At once it became plain to me that I must not use the obelisk itself in any way. There would be risk of damage - in fact almost the certainty of damage from treasure hunters. And as it has been our aim and prize in all this enterprise never to interfere in the smallest degree with the amenities of any district, and never to run the least risk of damage to what does not belong to us, this spot was clearly out of the question."

A little later in the piece, he added: "In view of many reports which may be read in the daily press just now, it is only fair that it should be known that the proprietors of Tit-Bits, the originators of this novel form of competition, have been guiltless of any action which could cause the rights of others to suffer. They have paid scrupulous regard, not only to their own interests and those of their readers, but also to the interests of the general public, and it is a fact that in no case have those interests been interfered with" (17).

That seems to be true. I have details of 98 treasure hunt hearings in my notes, and the damage done always seems to spring from a newspaper scheme like the Dispatch one. There's no evidence that any Tit-Bits clue ever led to the slightest vandalism or violence. Why should that be?

First of all, the Dispatch's clues began by narrowing each search to a specific town or, in the case of big cities, a specific borough. Tit-Bits, on the other hand, simply told readers that each prize was hidden somewhere in Britain and forced them to guess which town was involved. Randall's first task, you will remember, was deciding whether he should search Carlisle or Newcastle. The Tit-Bits scheme required readers to invest time and money travelling round the country, and that ruled out many of the thugs and vandals who caused so much trouble for the Dispatch.

In 1904, many labourers would have been barely able to read, let alone undertake the detailed library research Randall must have done. The Dispatch's clues required a degree of literacy and education to follow them too. But, once the scheme started to catch on, you could take part simply by listening to the local gossip or joining the biggest crowd of diggers you could find. Once it reached a certain critical mass, the Dispatch scheme would have started feeding on itself, pulling in passers-by who had never read the paper in their lives.

Finally, while the Tit-Bits scheme had bigger individual prizes, its total prize fund was much smaller. Tit-Bits offered a total of just £1,000 in prizes against the Dispatch's £3,790. The Dispatch also spread its bounty much more widely, using over 60 different locations against Tit-Bits' ten. All these factors combined to ensure that the Dispatch's scheme attracted far bigger crowds than the Tit-Bits one. Stir in a little mass hysteria, and the resulting chaos was almost inevitable.

Tit-Bits closed its January 30 piece by promising a new competition soon, but one which buried no real treasure. Readers would get another serialised story full of clues to hidden booty, but this time be asked to mark its location on a printed map. The first reader to send in a map marked in the right place would get his prize through the post. Pike and Meggs were allowed to complete their own quest the following week, when Gold in Waiting came to an end. Real-world treasure hunts, the paper had concluded, caused too many headaches.

Tit-Bits' publishers may have opted for the quiet life, but the Dispatch decided to fight on regardless. Its January 31 edition carried a front page banner directing readers to a new batch of clues on pages five and six. Fresh medallions had been planted in Leicester (£70), Plymouth (£50), Derby (£50), Swansea (£40), Northampton (£30) and Stroud (£20). The paper also started battling the bad publicity from its rivals by running a string of cosy stories profiling successful treasure hunters and showing how much their £50 windfalls had improved these deserving lives.

Some of these accounts are undeniably moving. William Steadman, who was out of work when he found the Bethnal Green medallion, used the money to set himself up as a boot-maker. "This is the starting point in my life," he said. Henry Cameron claimed finding the Canning Town medallion was "the first good luck I ever remember having, and it came at a time when I sorely needed it". Joseph Markham, who discovered the Stratford disc after colliding with a horse on the canal towpath, found the money was enough to complete the payments on a plot of land he was buying, get a few household necessities and add to his savings. Louise Cox, asked how she had spent the Bermondsey £50, simply said: "I clothed my children" (15).

Meanwhile, lawyers representing borough councils up and down the land were still looking for that elusive offender who would explicitly link the Dispatch to his own crime. The breakthrough came on February 1, when a Preston solicitor named WH Wilson won a summons joining The Newspaper Syndicate Ltd (TNSL) to an upcoming case. Four men were about to be tried for wilfully damaging the highway in Stretford and Prestwich, and Wilson's move meant the Dispatch's owners would be right there in the dock beside them. All through this affair, people had been wondering how to hold the paper accountable. Now, at last, it looked like someone had found a way.

Meanwhile, lawyers representing borough councils up and down the land were still looking for that elusive offender who would explicitly link the Dispatch to his own crime. The breakthrough came on February 1, when a Preston solicitor named WH Wilson won a summons joining The Newspaper Syndicate Ltd (TNSL) to an upcoming case. Four men were about to be tried for wilfully damaging the highway in Stretford and Prestwich, and Wilson's move meant the Dispatch's owners would be right there in the dock beside them. All through this affair, people had been wondering how to hold the paper accountable. Now, at last, it looked like someone had found a way.

It was Henry Caro, a postman, who turned out to be Wilson's key witness. He and three other men had been arrested for damaging the highway in Stretford and Prestwich towards the end of January. TNSL was accused of aiding and abetting their crimes and encouraging those crimes to be committed in the first place.

The case was heard at Manchester Police Courts on February 4. PC Lowther testified that he had been on plain clothes duty in Hodge Lane, Prestwich, at 2:00pm on January 24 when he saw Caro "cutting up the surface of the roadway with a large tin opener". Caro was quickly found guilty, and ordered to pay fines, costs and damages totalling six shillings and six pence. Fines of 40 shillings were quite routine by then, so Caro must have realised he had got off lightly. Wilson then questioned him about TNSL's role in the offence.

Caro confirmed that he would never have damaged the roadway if he had not read about the treasure hunt medallions in the Dispatch. He pointed out that the paper often referred to the medallions as being "buried" and that the particular clue he had been following specified that its man had "scooped out a hole in the ground" with his trowel before hiding the disc. Mr Yates, the presiding magistrate, ruled that the Dispatch's clues had influenced Caro and the other treasure hunters, and said it should be held responsible for the consequences of printing those clues. It was reasonable to assume that saying a treasure had been buried with a trowel - as the Dispatch had done - might well lead someone to try and dig it up. Therefore, the paper's owners had encouraged Caro's crime and must pay the price.

Yates ordered TNSL to pay a fine of £5 - worth £450 today - plus damages and 10 guineas in costs. The company had already lost an earlier objection, claiming that a corporation could not be properly tried under the law Yates had applied, but promised to renew that argument on appeal.

While the lawyers waited for an appeal date to be set, treasure hunters continued to dig up half the UK and the courts continued to slap big fines on those arrested for doing so. By February 5, news of the scheme had reached Australia, where the Sydney Morning Herald reported: "Many people have been prosecuted and fined for having damaged the roadway in making search. And the newspaper has been fined for aiding and abetting the searchers in causing damage" (18). Nothing daunted, the Dispatch carried a fresh set of clues in its February 7 issue, directing readers to medallions hidden in Bristol, Nottingham and Brighton.

And then, on February 14, everything changed. Suddenly, the Dispatch was missing its regular front page banner flagging up the treasure hunt scheme. The usual two broadsheet pages of clues and promotional copy inside had vanished too. Instead, readers found a page nine news story headlined: "The Great Treasure Hunt: End Has Come to the 'WD's' Great Money-finding Scheme". The story beneath began with five paragraphs of self-justification, reminding readers again of the paper's regular disclaimers that the medallions did not require tools to dig them up and stressing how very responsible and deserving it felt the majority of treasure hunters had been. Then it got to the meat.

"The interest taken in the treasure hunt has far surpassed the most optimistic expectations," the paper reported. "Our offices were besieged by crowds waiting to obtain early copies, and in the provinces hundreds of people waited at the railway stations in order to secure a copy of the Dispatch the moment the newspaper train arrived. In our printing works, extra machines had to be kept running for long hours to produce the enormous issues demanded by the public and we have again and again found it necessary to reprint the various editions. The result has been to raise the circulation of the Dispatch to nearly a million copies weekly.

"It is not by the wish of the proprietors that the treasure hunt has now reached its close. This has been entirely due to the fact that in certain quarters enthusiastic seekers for medallions have not followed or heeded our repeated and urgent warnings against causing annoyance or doing damage. As a natural result of this complaints have reached us and serious representations have been made to us by the authorities. Such representations we could only treat with the consideration and respect that they deserved, and we accordingly decided to bring the matter to a close on Friday last" (19).

The Dispatch added that 134 of its 177 medallions had been found by the time the scheme closed, and that these had been redeemed for a total of £2,935. That left 43 medallions, worth £855 in all, unaccounted for. These, it added, were now worthless, and should be regarded only as interesting curiosities.

A week later, it emerged that the Dispatch's change of heart had been prompted by an injunction against TNSL from London County Council's parks committee. This injunction was backed by the Attorney General, and had produced an undertaking from TNSL that the scheme would be dropped immediately.

That left only the matter of TNSL's appeal against Manchester Police Court's fine, which ended more happily for the publishers. Their lawyers argued before the King's Bench Division that, as the fine had been made under section 52 of the Malicious Damage Act 1861, it should not be allowed to stand. Section 52 allowed for magistrates to impose, at their discretion, either a fine or imprisonment, they pointed out. But TNSL was a corporation, and corporations could not be jailed. Therefore, no such discretion was possible, section 52 could not apply and the fine should be dropped. Mr Justice Wills reluctantly agreed, but added that he was "far from expressing any sympathy with the object of the motion" (20).

And that was that. The Greatest Treasure Hunt On Record had begun with an announcement in the Dispatch's January 3, 1904, edition, and ended with the publishers' enforced decision to pull the plug on February 12. The six weeks intervening created a trail of damage throughout London, wasted an enormous amount of police and court time and sent thousands of people off on the most ludicrous adventures. Very many people were inconvenienced, some had their gardens ruined and a few got thumped through no fault of their own. On the other hand, the scheme also made 134 dreams come true and provided a great deal of innocent amusement for anyone following its twists and turns in the press. It would take a very dull soul to wish it had all never happened.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the Islington Archaeology & History Society Newsletter in 2006.

Postscript: a medallion unearthed

When this essay first appeared, I added a note asking any reader who might have a Weekly Dispatch medallion squirreled away in the attic to contact me. My friends were sceptical, arguing the medallions were probably so flimsy that they'd be no more than scraps of tin foil by now, but I was convinced an intact specimen would show up one day.

When this essay first appeared, I added a note asking any reader who might have a Weekly Dispatch medallion squirreled away in the attic to contact me. My friends were sceptical, arguing the medallions were probably so flimsy that they'd be no more than scraps of tin foil by now, but I was convinced an intact specimen would show up one day.

My faith was rewarded in December 2013, when a surviving medallion finally came to light. It hadn't been hiding in a reader's attic, however, but four inches beneath the surface of Plymouth's Brickfields Recreation Ground, where supermarket worker Alvaro Casares found it with his metal detector.

"I found the medallion behind Plymouth Albion," he told me. "When I first retrieved it from the soil, I thought it was a medal. It was covered in mud. Once I got home, I cleaned it with warm soapy water, then Googled the Weekly Dispatch and it took me to your link for The Treasure Hunt Riots. I read all the information with interest and was excited that I had found one of the medallions. That's why I love detecting for historical items. It's not just about the coins - it's about the history of the items I find."

Plymouth Albion Rugby Club is in the south west corner of Brickfields, close against its Madden Road boundary. As you can see from his photographs here, Casare's £10 medallion measures about 6.5cm from side to side - a figure I've now been able to correct in my original essay - and has the word "Hidden" stamped on its reverse side. Casares tells me it's made of lead and thick enough to resist any attempt to bend or mangle it.

Now that I knew a medallion had been buried at Brickfields, I went back to my folders of Weekly Dispatch clippings and found a January 31, 1904 story confirming its reporter had just planted four medallions in Plymouth and that he'd chosen the neighbourhood around Brickfields as one of his targets. The paper calls this its "Stonehouse District" medallion and the reporter specifically mentions Brickfields as one of the spots he visited. The other three Plymouth medallions ended up in Laira, Devonport and St Jude's.

In the paper's next edition, dated February 7, its reporter describes getting off the early morning train from Paddington at Mill Bay Station (now the site of Plymouth Pavilions) and setting off to conceal the Stonebridge District medallion first. He writes:

"First, I went to the 'brickfields'. Only half-way up the hill I climbed, for the ground was soft and slippery, and I could hardly keep my balance. It was near here that a man startled me by demanding my 'disc'. I was relieved, however, on finding that the disc he wanted was a halfpenny - for toll."

The toll he mentions was almost certainly that charged at Plymouth's Halfpenny Gate, which people then had to pass through to cross Stonehouse Creek on the other side of the recreation ground. That spot's just 400 yards from where the medallion was eventually found and forms part of a fairly logical route from the station through the heart of Stonehouse itself to what's now Plymouth Albion's ground. I sent the Plymouth historian Derek Tait another of the paper's Stonehouse District clues, where he thought he could detect references to both the Union Street bridge next to Mill Bay Station and to the nearby Palace Theatre. All these locations lie well within a mile of each other, giving the WD reporter plenty of time to explore the whole area in the 50 minutes or so he had at his disposal before moving on to Laira.

Graham Naylor and Lorna Basham at Plymouth's central library kindly searched their 1904 local newspaper archives for me, where they uncovered a Western Morning News ad for the treasure hunt itself. It appeared in the WMN's February 6, 1904, issue and reads: "Weekly Dispatch Treasure. Over £2,000 still undiscovered in this district and elsewhere." The ad was evidently worded to make unwary readers think there was over £2,000 up for grabs in the west country alone, but in fact that's a national figure, representing just over half of the £3,790 worth of medallions the WD buried altogether. It's that phrase "and elsewhere" which provides the weasel words here, and no surprise to see they appear in the ad's smallest type.

Any medallion found by WD readers had to be presented at the paper's London offices before it could be swapped for cash, and the newsdesk very often took advantage of this by trumpeting the find in its next edition. I've been unable to find any story about a Plymouth medallion's discovery in the copious WD material I've collected, however, which suggests all four were still undiscovered when the whole scheme was forced to close on February 14, 1904. At that point, the paper declared all the remaining medallions worthless, so any searches already in progress were simply abandoned.

Most likely, then, Plymouth's three other prizes are still lurking in the soil there, waiting for Casares or another local metal detector enthusiast to uncover them. His find this November reduces the number of discs still unaccounted for throughout the UK to just 42, but who's to say one of them isn't buried in your own town?

Appendix I: Forger's leap lands him in the mire

The Dispatch's treasure hunt scheme provided a steady flow of human interest stories for the paper and its rivals. Here's just a few of the more colourful tales they reported.

* A forger caught planting fake medallions in Stratford to distract his rivals leaps on to a rotting barge to escape the angry mob chasing him. It promptly collapses, dumping him in the sludge beneath. (Weekly Dispatch, 31/1/1904).

* Liberal peer Lord Burghclere, addressing a public meeting, attacks his Conservative opponents by saying: “Their art was the art of the purveyor of fancy soap and the concealer of hidden treasure” (The Times, 30/1/1904).

* Joseph Markham, a Manor Park labourer, is searching a canal towpath for the Stratford £50 medallion, studying the ground so closely that he collides with a horse coming the other way. Picking himself up, he finds the disc on that very spot (Weekly Dispatch, 31/1/1904).

* Dispatch reporters spot a blind man among the crowds of treasure hunters in Chelsea (Weekly Dispatch, 24/1/1904).

* Six-year-old Charlie Daley's mother is so overcome when she finds Deptford's £50 medallion that she faints dead away. Fortunately, Charlie has the presence of mind to grab the disc and conceal it from the crowds flocking round to help (Weekly Dispatch, 24/1/1904).

* One week the Dispatch runs its treasure hunt copy above a piece of sheet music for its readers to collect and play. The tune selected is “All That Glitters Is Not Gold” (Weekly Dispatch, 31/1/1904).

* Treasure hunters outside St Mary's Church in Islington are frustrated by a stubborn policeman who refuses to let anyone loiter there. The £50 medallion is later found exactly where the policeman had been standing (Weekly Dispatch, 7/2/1904).

Appendix II: Holmes and Watson join the quest

"Pike smiled. 'Now what was your latest impression of that name? You heard it more than once I believe?'

"Pike smiled. 'Now what was your latest impression of that name? You heard it more than once I believe?'

'Yes,' Mr Meggs replied. 'I heard it more than once, but I never felt quite certain about it. I'm pretty sure, however, that the surname wasn't Green, but Dean. I think Edmond Dean was as near the sound as possible. Perhaps Desmond.'

'Ah,' Pike put his notes carelessly in his pocket. [...] 'Your friend Mr Green,' he said, 'is neither Edward Green nor Edmond Dean, but Jesmond Dene, unless I'm sadly mistaken, and Jesmond Dene is a place about two miles away.'"

- Gold in Waiting, Tit-Bits, Jan 2, 1904.

It's no coincidence that the characters of Pike and Meggs read so much like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Holmes and Watson. Just like Watson, Meggs can act as a stand-in for the reader's incomprehension, helping us to understand what's going on as Pike explains it to him. But there were sound commercial reasons for aping Holmes and Watson too.

Sherlock Holmes was at the peak of his early popularity in 1904. Conan Doyle's decision to kill off the detective in 1893's The Final Problem had sparked a period of national mourning and widespread public protest. This was replaced by rejoicing when The Hound of the Baskervilles began its serialisation in The Strand Magazine - Tit-Bits' sister publication - in 1901.

Readers queued outside the magazine's offices for each new episode of that story, sending The Strand's circulation soaring overnight, just as they would queue outside the Weekly Dispatch's office three years later.

Conan Doyle had been careful to set Hound before Holmes' fateful visit to The Reichenbach Falls, but was eventually forced to surrender altogether to his readers' demands and announce - in 1903's The Empty House - that Holmes had faked his death all along. No wonder Tit-Bits decided that cashing in on the renewed Holmes craze was the way to promote its own competition.

This point did not escape Ralph Cleaver, The Illustrated London News cartoonist, either. The paper's January 30, 1904, issue carried a full page of Cleaver's cartoons mocking the treasure hunt craze.

One shows a tall, top-hatted fellow surveying the sign on his new office door. It reads: "S Holmes Watson & Co. Treasure seekers ass'tn. Expert searchers. Always ready. Clues promptly followed up by Dr Cunnin Toyle". The Tit-Bits duo's inspiration couldn't be made much more explicit than that.

Appendix III: Mounted troops clear Woolwich Common crowd

The Weekly Dispatch announced on January 17, 1904, that it had hidden a £50 medallion in the south-east London district of Woolwich.

The accompanying clue mentions two "large blocks of buildings devoted to official purposes connected with the defence of the country". Readers concluded these must be the military barracks on Woolwich Common, and headed over there in great numbers.

Here's a few press extracts describing what happened next:

* "TREASURE-SEEKERS PUT TO FLIGHT: A CHARGE BY TROOPS AT WOOLWICH." -Northern Daily Telegraph headline, January 25, 1904.

* "Before daybreak yesterday people poured into Woolwich in thousands, and proceeded to the south part of the common, opposite the Royal Herbert Hospital and near the Ha Ha Road. Here they commenced to probe and dig in the most reckless way, reducing this beautiful piece of ground to wreck." - The Globe, January 25, 1904.

* "At nine o'clock affairs had arrived at such a pass that a detachment of the Garrison Mounted Police was ordered to clear the common. The treasure-seekers were infuriated, and but for the presence of the thousands of troops in the adjoining barracks, there would undoubtedly have been a riot." - St James's Gazette, January 25, 1904.

* "As it was, the troops were subjected to a considerable amount of abuse. Hundreds of the baffled remained for many hours lining the roadway and gazing longingly at the spot where they were persuaded the coveted medallion lay." - Bolton Evening News, January 25. 1904.

* "No-one has a right to incite people to injure public property, and no legal authority ought to hesitate to put a stop to a system of lawlessness. Things are becoming serious when it is necessary to clear Woolwich Common by the aid of the military to prevent a fine open space being torn up with picks and shovels." - Islington Gazette editorial, January 26, 1904.

* "The Government prosecuted six men at Woolwich yesterday for damaging Woolwich Common. Evidence showed that crowds of people rushed the military and town police in their search for buried treasure, and the military had to close the common. [The magistrate] fined each prisoner 10s and 1s costs or ten days. He would punish more severely future offenders." - Northern Whig, January 26, 1904.

In June 2017, Islington Museum helped me reconstruct the full journey described by a 1904 Weekly Dispatch clue. To read the results of our deductions, visit PlanetSlade's July 2017 letters page here.

Sources

1) The Times, January 15, 1904.

2) The Times, January 19, 1904.

3) Manchester Evening News, January 18, 1904.

4) Encyclopedia of the British Press 1422-1992, ed Dennis Griffiths (St Martins Press, 1992)

5) World Press Encyclopedia, ed George Kurian (Mansell, 1982)

6) Tit-Bits, January 9, 1904.

7) Read All About It: 100 Sensational Years of the Daily Mirror, by Bill Hagerty (First Stone, 2003).

8) Weekly Dispatch, January 17, 1904.

9) Manchester Evening News, January 16, 1904.

10) Weekly Dispatch, January 24, 1904.

11) Islington Gazette, January 26, 1904.

12) The Times, January 20, 1904.

13) The Times, January 27, 1904.

14) Islington Gazette, January 28, 1904.

15) Weekly Dispatch, February 7, 1904.

16) Manchester Evening News, January 29, 1904.

17) Tit-Bits, January 30, 1904

18) Sydney Morning Herald, February 5, 1904.

19) Weekly Dispatch, February 14, 1904.

20) The Times, February 27, 1904.