May: Tracing The Wellman Correction

Like many journalists with roots in the age of print, I have a great fondness for embarrassing newspaper corrections. These short pars – often printed only to stave off the threat of legal action – are a great source of unintentional comedy. Editors used to hate having to run them, fearing they’d undermine readers’ trust in the paper’s factual reliability, and this often led to corrections being worded in such an evasive way that they became all the funnier.

My favourite example is a correction I first heard quoted in the early 1980s and liked enough to memorise on the spot. I call it The Wellman Correction, and it goes like this:

"Instead of being arrested yesterday as we stated for kicking his wife down a flight of stairs and hurling a lighted kerosene lamp after her, Revd. James P. Wellman died unmarried four years ago."

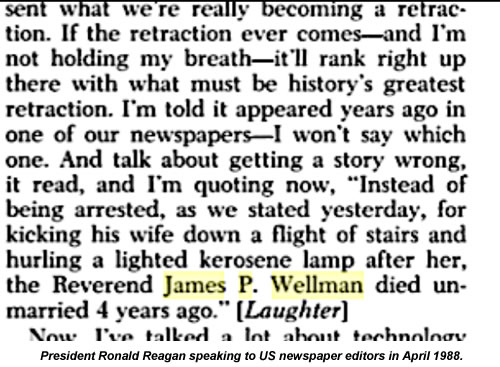

I’ve seen it cited dozens of times since, first by newspaper columnists needing a quick humour item to fill out their copy, and later by a host of internet bloggers. It’s an irresistible opportunity to raise a quick laugh at someone else’s expense, while also wryly acknowledging that even the best reporters don’t always get it right. The correction’s appeared in at least one published anthology (Geoffrey Madan’s 1985 Notebooks), was once quoted in a speech by President Ronald Reagan and continues to pop up online pretty regularly today. What all these pieces – and I really do mean all - have in common is a failure to name which newspaper carried the correction, or the date on which it appeared.

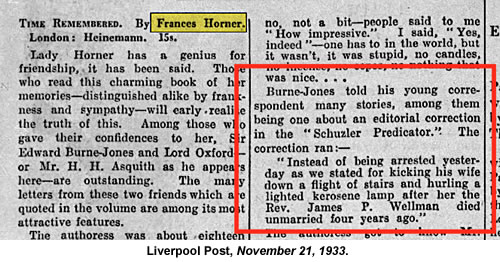

Thinking about all this a few weeks ago, it occurred to me that I now have a Newspapers.com subscription, and that the site’s eminently searchable database might let me trace the correction’s origins once and for all. My first discovery on the long trail that followed was this book review from the Liverpool Post of November 21, 1933:

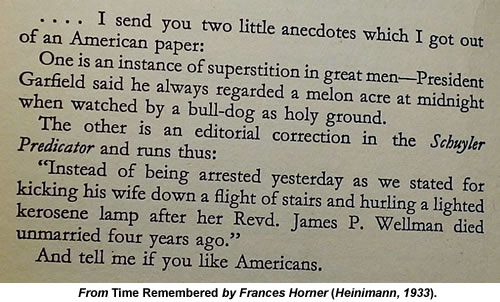

Job done, right? The newspaper that got Wellman’s story so wrong was called the Schuzler Predicator, and the correction must have appeared in June 1898 at the very latest – because that’s the month Burne-Jones died. Before hoisting the Mission Accomplished flag, though, I thought I’d better check Horner’s 1933 book at the British Library just to make sure the Liverpool Post review had quoted her accurately. I’m glad I did, because the relevant page in Time Remembered gives us a precise date for Burne-Jones’ letter – May 23, 1895 – and quotes the relevant section verbatim:

There’s a couple of points there. First, Burne-Jones’ reference to “two little anecdotes” suggests that what he saw was not the original correction itself, but an early example of another newspaper making fun of it. If that’s the case, we need to take his attribution with a pinch of salt. You’ll see also that he names the paper he’d read not as the Schuzler Predicator but the Schuyler Predicator (with a “y”), which sounds altogether more likely.

Sure enough, when I checked the library’s US gazeteers, I found no community anywhere in America called Schuzler. There were five places called Schuyler, but only two which looked big enough to have ever supported their own newspaper. These were a town called Schuyler in Colfax County, Nebraska – the county seat in fact – and Schuyler County in New York State. Newspapers.com turned up four newspapers with Schuyler in their names, all of them based in Nebraska: the County Republican, the Messenger, the Herald and the Sun. But there was no mention there of a paper called the Schuyler – or even the Schuzler – Predicator. The Library of Congress’s online newspaper archive has no record of a paper using one of those names either. New York’s Public Library lists a paper called the Schuyler County Courier, but has only 20th century copies in its collection. When I contacted Nebraska’s state library, they turned out to have no matching titles in their collection either

Before ploughing on, I decided to see if I could put a rough time frame on the clipping. Portable kerosene lamps – which is to say those small enough to hurl downstairs – were invented only in the 1850s. That gave me a manageable window to work within: let’s say 1850-1900. Back to the newspaper archive I went, where a search for “Wellman + kerosene” over that half century produced this clipping from the Selma Times of November 29, 1885:

The guilty newspaper’s name is now given as the Schuyler Vindicator – rather than Predicator – and we can be a lot clearer that it’s the original correction being discussed rather than a later recycling of it. So let’s try Schuyler Vindicator as one of our search terms.

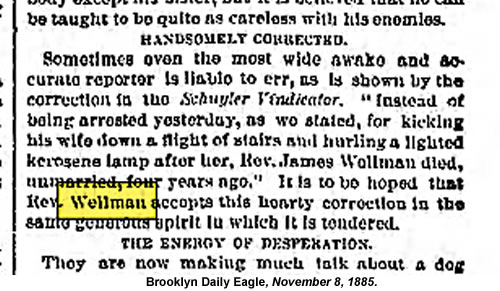

Bingo! This produced 37 identically-worded clippings from 13 different states, almost all of them appearing in November or December 1885. The earliest one of the lot was this November 8 item from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

That paragraph ran as one of 16 short humour items under the collective headline “Burdette” – a name which also appears topping the Selma Times’ account. Even the par’s headline and its couple of sentences of framing copy were identical in all the 37 clippings I’d found, so my first thought was that it might be wire service copy, distributed by an agency called Burdette for all its client papers to reproduce if they chose. But that wasn’t it.

In fact, the word turned out to be a credit for Robert Jones Burdette (1844-1914), a leading newspaper funnyman of his day. “He joined the staff of the Burlington Hawkeye in 1872, and his humorous paragraphs soon began to be quoted in newspapers throughout the country,” says Wikipedia. “In 1884, he left the Hawkeye to replace Stanley Huntley as the staff humorist for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.” A modern parallel might be Dave Barry, whose syndicated humour column ran in as many as 500 papers in the early 2000s.

It’s only natural that Burdette would have wanted his Wellman story to appear in his own newspaper first, so I’m happy to assume the November 1885 clipping above is the earliest item poking fun at the correction. Everyone else evidently reproduced it either as a piece of syndicated copy from Burdette’s column, or simply by stealing it when November 8’s BDE was published. What’s not clear is whether Burdette was reporting a genuine correction which he’d actually seen in a real newspaper called the Schuyler Vindicator or had just made the whole thing up from scratch.

Much as I’d like to believe The Wellman Correction is real, I have to admit that I’ve now got my doubts. It’s certainly possible that the Schuyler Vindicator had too small a circulation for any copies to survive into our age – let alone to be preserved in an online archive – but my failure to find any mention of even its name in the historical record makes that theory look shaky. I’ve searched online birth and death records throughout the US for a James Wellman who died somewhere round the 1881 date Burdette implies, but found no-one who fits the bill there either. Some candidates turned out to be married when they died, some had died in infancy and so on.

None of these doubts have damaged the clipping’s popularity in the least. By January 1886, it had crossed the Atlantic – where the Lancashire Chronicle was first to run it – and it’s been in more or less constant circulation for the whole 140 years since. A quick Google search earlier today revealed someone quoting it as recently as June 2022 on this Bengali website, so there’s clearly no end in sight just yet.

The fact that the correction itself is always quoted so accurately is a measure of how firmly its wording has become embedded in journalistic folklore. It seems even to have made its way into Ronald Reagan’s famous shoebox of folksy press clippings, giving him just the anecdote he needed for an April 1988 speech to US newspaper editors. I love his pretense of discretion here – “I’m not going to say which one” – when what he really means is that neither he nor his speechwriters had any idea which paper the correction appeared in either:

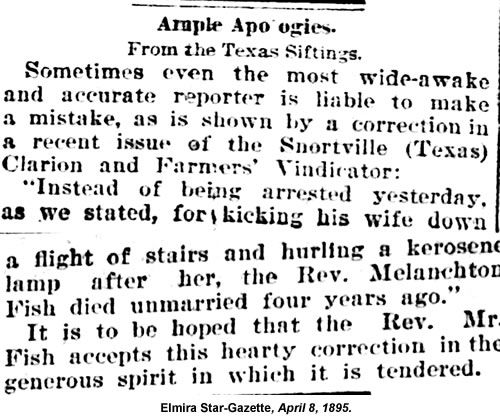

One last clipping, then we’ll wrap this up. The Nebraska State Library staffer who’d replied to my query attached this April 8, 1895 clipping from a New York State paper called the Elmira Star Gazette:

As you’ll see, the wording is quite familiar. Quite why this paper waited ten years before running its own version of Burdette’s story, I don’t know. The bigger mystery is why it chose to substitute such ridiculous names for both the individual mentioned in the correction and the newspaper where it supposedly appeared. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Snortville, Texas turns out to be a fiction too.

The only other reference I’ve been able to find to a Reverend Melanchton Fish is a mocking anecdote about a Black preacher of that name, which ran in several white American newspapers of the late 1880s. That anecdote itself reads like pure folklore to me, so maybe the Star-Gazette’s man lifted the name from a fictional Black archetype whose supposed foolishness was then a source of amusement to racist whites? My only other notion is that it might be a veiled reference to Dr Melancthon Fish, a prominent white doctor in New York State at that time. If so, quite what point the Star-Gazette was hoping make about him defeats me.

July 5. 2023: Jesse DeNatale of California writes:

“Somehow today I was lead to your website and discovered your section on murder ballads. I had just been thinking (because of all the gun violence here in America) about a song I wrote a number of years ago after the killing of young Oscar Grant on New Year’s Eve at the Fruitvale Station in Oakland, California.

“I wrote the song a few days later - long before they made a movie about it called Fruitvale Station. It's called The Ballad of Oscar Grant. I had played the song many times live but didn't record it until 2018. It came out on a record I did in 2020 called The Wilderness.

“At an event a few years ago I sat next to the folksinger Paul Brady at a round robin song share. After Paul sang a murder ballad, I realized that I had one of my own and sang the Oscar Grant song. (Side note: he liked it very much.) It was only then that I started to consider the song just that - a murder ballad.”

Paul Slade replies: Thanks very much for that, Jesse – I like the song. I’m not sure how much news coverage Grant’s 2009 death got here in the UK at the time, but I certainly don’t recall reading about it before. I see Dave Rovics also wrote a song about the case.

Over here (and right around the world, of course) it was George Floyd’s murder in 2020 which made most impact, sparking a lot of Black Lives Matter graffiti and many home made posters in my little corner of London.

Schoolboy cryptography of WW1

The four images above are all taken from a batch of 130 World War One postcards which I found on a stall at my local market. Two things grabbed my attention about them: first, that nearly all were sent by someone named Robin to a Miss CM Turton (addressing her by the nicknames “Cheetah’ or “Bunji”) at the family seat in Yorkshire and, second, that Robin had chosen to write some of them in code.

Given the cards’ vintage – all are postmarked between 1914 and 1916 – my imagination immediately went into overdrive. Were these encrypted cards secret love notes from a soldier at the front, writing to his sweetheart back home? Was Miss Turton perhaps a British intelligence agent, gathering information from her undercover operatives in occupied Europe? The truth turned out to be rather more mundane, but still the cards had an interesting tale to tell.

Looking into the Turton family, I quickly discovered that the cards’ sender was Robin Turton, later to become Baron Tranmire, who spent the Great War as a boarder at Eton. “Cheetah” remains a little harder to identify, as the family had a tradition of naming its daughters Cecilia and giving them all a middle name beginning with M. One candidate would be Robin’s mother, Cecilia Mary Turton, but there are many others. Robin’s messages on some of the cards – the uncoded ones in this case – refer to him collecting postcards, which is doubtless why the batch of cards I found remained together for so long. How they ended up on a junk shop stall, I don’t know.

Robin Turton became a Conservative MP in 1929, rising through the party to become Anthony Eden’s Health Minister. He joined the Green Howards at the outbreak of World War Two and was awarded the Military Cross for his service there. Returning to Parliament after the war, he became Father of the House in 1965, a title awarded to the Commons’ longest-serving member. The same title is now held by Robin’s nephew Sir Peter Bottomley MP, a former member of Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet.

“Robin Turton helpfully gave a reference that helped my way to Parliament,” Sir Peter told me when I contacted him about the cards. “Alternate first daughters and some others were named Cecilia, so the name has been shared by my great niece, my daughter, my sister, my aunt and my grandmother, together with a cousin or two. The nicknames mean nothing to me.”

As for the coded cards, I posted images of these online both as Twitter threads (1, 2) and as queries on Metafilter (1, 2), where wiser heads than mine were quick to decipher them. None of the cards tackled there proved quite as interesting as I’d hoped – just schoolboy trivia, really - but I found the various methods people used to solve them fascinating. BobTheScientist, one of the guys who helped out via Metafilter, has an excellent blog post explaining his own approach here.

March: Langridge + Gerhard

A few months ago, I sent the Canadian comic book artist Gerhard a B&W copy of Roger Langridge’s earlier PlanetSlade art, and commissioned him to add one of his trademark backgrounds. Just as with Dave Sim’s Cerebus – the book where Gerhard made his name – I thought the combination of Roger’s cartoony figures and Gerhard’s detailed draftsmanship would work well. And so they did.

The idea was never to replace Roger’s original, which remains safely framed in my hallway, but simply to provide a bonus postscript. “This is rather wonderful,” Roger replied when I sent him a copy of the hybrid art. “A lovely surprise.”

Gerhard has posted the new piece on his own site here, along with an animated gif showing his process in tackling it stage-by-stage. You can see Roger’s original colour art in all its glory on this PlanetSlade page (which also has guide identifying the nine murder ballads characters shown)). To admire my earlier PlanetSlade commission from Gerhard – flying solo this time – click here. And don’t forget to also visit Roger’s HotelFred page, where you can find much more of his own wonderful art and buy his books. Is that enough links? I think it probably is.

February 15. Dave Arthur of Rattle on the Stovepipe writes:

“I’ve just finished Black Swan Blues and I thought it was a terrific read. So much information about the early days of urban blues recording and the unbelievable battle to get black composers and artists a fair deal. Also interesting was the hypocrisy of white audiences about black performers - happy to employ them to play music and enthusiastic live audiences, but racially prejudiced and abusive when back in the 'real world'. It’s no wonder half of Ethel Waters’ band decided against touring in the Deep South when you realise how many lynchings were taking place in the 1920s.

“I loved all the names and characters that popped in and out of the story such as Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Paul Robeson etc and was impressed with Waters’ very perceptive comments on her life and music. Obviously a very bright woman.

“It was not only remarkably informative but a really good read. It was the other side of the blues coin from my usual country blues interest. It really was one of the best books on the blues I've ever read. Unfortunately, I've now got to go through the bibliographic notes and try and hunt down all the biographies and reference books you mention! As if I needed any more books!”

Paul Slade replies: Thanks very much for the kind words, Dave - I’m really glad you liked the book. If you are going to dig into the bibliography, I think Waters’ His Eye is On the Sparrow should be your first stop. She’s very frank about everything she had do to survive over the years, and the book’s got a nice conversational tone of voice.

My impression is that she simply unloaded hours and hours of memories and anecdotes to her ghost writer, who had the good sense not to monkey with it any more than he had to as he put it on the page. There are biographies of Waters which are more reliable when it comes to exact dates and details like that, but this one’s far more entertaining and evocative to read.

February 8. Jim Deutsch of the Smithsonian Center for Folklore writes:

Your article, True Lies: The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, is very impressive. One question I have concerns the citation for the full-length photo of Hattie Carroll, which you say appeared in the February 23, 1963, issue of the Baltimore Afro-American. All of the February 1963 issues of this newspaper are now available online through Google, where it appears that this particular photo ran in the issue of February 16, not February 23.

Paul Slade replies: Thanks very much for getting in touch. I’ve just checked your archive link and, yep, you’re quite right. I must have mis-transcribed that date either when preparing my notes for the article or when actually writing it. I’ve corrected the date now. No writer enjoys being caught out in a mistake, but I’m always glad of the chance to improve the site in these small ways.

I don’t know how long Google has had that archive of the Afro-American online, but what a fantastic resource it is! America’s Black newspapers give a very different perspective on any story with a racial element to it - especially when you go back to the lynching era – and yet their archives remain far harder to find online that those of their white counterparts.

When I originally researched Hattie Carroll ’s story, I was working from paper copies of the A-A held in Baltimore’s County Library, which a staffer there very kindly photocopied and e-mailed to me here in London. If I hadn’t been lucky enough to find such a helpful and conscientious librarian there, I’d have had no access to the paper at all.