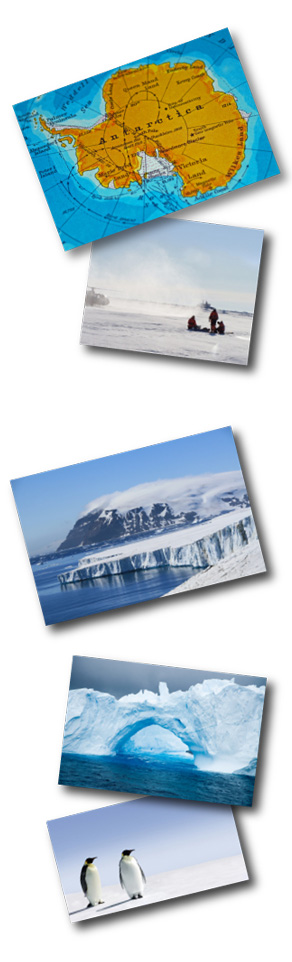

On the 15th November I will leave London and set off on an adventure like no other. Flying via Santiago in Chile, the first stage of the expedition begins upon reaching Punta Arenas, one of the most southerly cities in the world. There I join a six-strong team of international adventurers making the attempt on the Pole. Last minute preparations and briefings on the weather conditions in the Antarctic will see us through to the 20th when, weather permitting, we will depart for Patriot Hills in Antarctica.

Landing on an ice-runway near the base camp at Patriot Hills, we will unload our sledges (or pulks) and spend a vital couple of days checking our gear on the ice and snow. Assuming all’s well, we will then fly out by Twin Otter ski-plane to the coast. From there the expedition begins in earnest.

Facing Katabatic headwinds that are likely to be 15-20km/hr on average, but can blow up vicious blizzards of more than 100km/hr, we will begin our daily grind of dragging our 70 kilo sledges behind us. While this weight will slow our progress to little more than 3km/hr, it comprises the supplies of fuel and food that will keep us alive in this icy desert over the next fifteen days or so, when we reach our first of two resupply points.

Skiing on cross country skis named after the first man to reach the Pole, Roald Amundsen, the ‘skins’ that cover the underside of the Amundsens will allow us to climb the gradient from the coast at an elevation of c.300m to the South Pole at an elevation of c.2,835m. Each day will see us skiing for some eight hours with just five minutes break each hour – it’s too cold to stop for longer! The air temperature will average around -30c, but the wind chill will add its effect to force the apparent temperature down to -50c or so. Temperatures this low can cause frostbite in minutes, and so losing a glove to the wind is nothing short of disastrous.

Each night we will pitch our tents speedily and begin the lengthy process of cooking. Most of our ood supplies will be dehydrated rations that will require rehydration by melting snow and boiling the water. In the Antarctic, this can take hours. Then after checking in with base camp to let them know all’s well, we will relax, chat and write our diaries. Sleep will come easily after a day pulling a sledge, expending upwards of 6,000 calories in the effort. Eye masks are required though, as outside it’s still daylight – during the Antarctic summer, we will experience daylight 24 hours a day.

Apart from the cold, the other main hazards we face will be crevasses and sastrugi fields. Crevasses we will hope to avoid with good navigation, but they are often well hidden until discovered too late; the sastrugi we will inevitably come across. These are vast fields of wind-created ridges of snow and ice, growing to around one metre high. Apart from making the already arduous process of sledge-dragging even more gruelling, they can easily cause the sledge to tip over: something that unquestionably costs valuable time and energy (two valuable commodities out here) and can easily be more dangerous than that.

After 40 to 45 days we should be in reach of our goal. It’s a long uphill slog, 934km to be exact, but with fortune on our side and we are successful in reaching the South Pole, we will become part of a small group of adventurers who have succeeded in journeying to the Pole from the coast of Antarctica. To date that group numbers just 219 ever, and many of those were assisted by motor, kite or dogs. Those that have completed the journey without artificial assistance number fewer than 140.